user45

|Suscriptores

Últimos

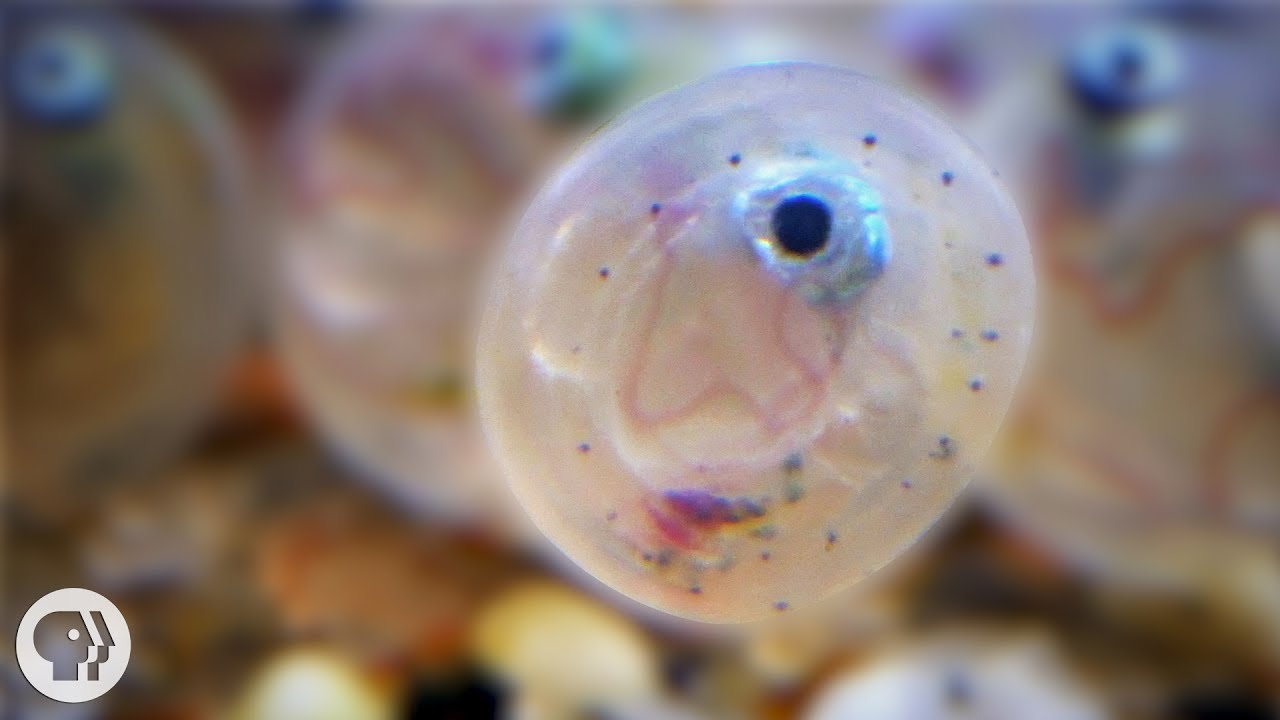

During the highest tides, California grunion stampede out of the ocean to mate on the beach. When the party's over, thousands of tiny eggs are left stranded up in the sand. How will their lost babies make it back to the sea?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

With summer just around the corner, Southern California beaches are ready to welcome the yearly arrival of some very unique and amorous guests. That’s right, the grunion are running!

California grunion are fish that spend their lives in the ocean. But when the tides are at their highest during spring and summer, grunion make a trip up onto beaches to mate and lay eggs.

Grunion mate on beaches throughout southern California and down into into Mexico. The grunion runs have taken on a special importance to coastal communities Santa Barbara to San Diego.

For some, coming out to see the grunion run has been an annual tradition for generations. For others it’s a rare chance to catch ocean fish with their bare hands.

--- What are grunion?

California grunion are schooling fish similar to sardines that live in the Pacific Ocean that emerge from the sea to lay their eggs on the sand of beaches in Southern California and down the Baja California Peninsula in Mexico. There are also smaller populations in Monterey Bay and San Francisco Bay. Another species, the Gulf Grunion lays their eggs in the northern shores of the Gulf of California. California Grunion are typically about six inches in length.

--- Why do grunion mate on land?

The ocean is full of predators who would like to gobble up a tasty fish egg. The grunion eggs tend to be safer up on the beach if they can make it there without raising the attention of predators like birds and raccoons. Grunion eggs have a tough outer layer that keeps them from drying out or being crushed by the sand.

--- When do California grunion run?

California grunion typically spawn from March to August. The fishing season is closed during the peak spawning times during May and June. See https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/fi....shing/ocean/grunion# for more detailed info on grunion seasons.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/06/06/these-fish

---+ For more information:

http://www.grunion.org/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Sea Urchins Pull Themselves Inside Out to be Reborn | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ak2xqH5h0YY

Sticky. Stretchy. Waterproof. The Amazing Underwater Tape of the Caddisfly | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z3BHrzDHoYo

The Amazing Life of Sand | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VkrQ9QuKprE&list=PLdKlciEDdCQDxBs0SZgTMqhszst1jqZhp&index=51

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

How Much Plastic is in the Ocean? | It's Okay To Be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YFZS3Vh4lfI

White Sand Beaches Are Made of Fish Poop | Gross Science

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1SfxgY1dIM4

What Physics Teachers Get Wrong About Tides! | Space Time

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pwChk4S99i4

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate based in San Francisco, serves the people of Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial media. Home to one of the most listened-to public radio station in the nation, one of the highest-rated public television services and an award-winning education program, KQED is also a leader and innovator in interactive media and technology, taking people of all ages on journeys of exploration — exposing them to new people, places and ideas.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #grunion #grunionrun

Besides being hermaphrodites — all snails have both boy and girl parts — they stab each other with “love darts” as a kind of foreplay.

SURVEY LINK: http://surveymonkey.com/r/pbsds2017

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

The sex life of the common snail is anything but ordinary.

First, they’re hermaphrodites, fitted with both male and female reproductive plumbing, and can mate with any member of their species they want.

Sounds easy, but the battle of the sexes is alive and well in gastropods.

In nature, fatherhood is easier. It’s the quickest, cheapest way to pass on your genes. Motherhood requires a much greater investment of time, energy, and resources.

During courtship, the snails will decide who gets to be more father than mother. But their idea of courtship is to stab each other with a tiny spike called a love dart.

The love dart is the snails’ tool for maximizing their male side. It injects hormones to prevent the other snail’s body from killing newly introduced sperm once copulation begins.

When snails copulate, two penises enter two vaginal tracts. Both snails in the pairing transfer sperm, but whichever snail got in the best shot with the dart has a better chance of ultimately fertilizing eggs.

In some species, only one snail fires a love dart, but in others, like the garden snail, both do.

You can spot love darts sticking out of snails in mid-courtship, and even find them abandoned in slime puddles where mating has been happening.

Scale it up to human size and the love dart would be the equivalent of a 15-inch knife.

--- How common is hermaphroditism?

Less than one percent of animal species are hermaphrodites. They’re most common among arthropods, the phylum of life that includes snails.

--- How do hermaphrodites decide who’s going to the male and female?

In most cases, both individuals will be both male and female, to some extent. Sometimes, like with garden snails, it’s a question of degree.

--- Can a love dart kill the snail?

In theory yes, but not very often. One researcher told us that in the thousands of matings he’s observed, he’s seen only one snail die that way.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/03/14/everything

---+ For more information:

Visit Joris Koene’s site. He’s one of the world’s foremost snail and slug researchers: http://www.joriskoene.com/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Banana Slugs: Secret of the Slime

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mHvCQSGanJg

The Ladybug Love-In: A Valentine's Special

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c-Z6xRexbIU

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Gross Science: Help a Snail Find True Love!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vfkb2XyswJY

4 Valentine's Day Tips From the Animal World!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5lMa9CYG3SU

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED. education

#deeplook

DEEP LOOK - see the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Twice a month, get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small. DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios.

SUBSCRIBE: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

All-NEW EPISODES EVERY OTHER TUESDAY!

#deeplook

DEEP LOOK - Watch science and nature videos up close (really, really close). Twice a month, get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small. DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios.

SUBSCRIBE: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

All-NEW EPISODES EVERY OTHER TUESDAY!

More about our new host, Lauren Sommer: http://blogs.kqed.org/pressroo....m/deeplooknewhostvid

#deeplook

DEEP LOOK - see the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Twice a month, get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small. DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios.

SUBSCRIBE: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

All-NEW EPISODES available now!

#deeplook

Every winter, California newts leave the safety of their forest burrows and travel as far as three miles to mate in the pond where they were born. Their mating ritual is a raucous affair that involves bulked-up males, writhing females and a little cannibalism.

SUBSCRIBE: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

These amphibious creatures are about five to eight inches long, with rust-colored skin, except for their bright yellow eyes and belly. They began to arrive at the UC Botanical Garden around November, and will stay here for the duration of the rainy season, usually through the end of March.

While California newts (Taricha torosa) are only about six inches long, they might travel as far as three miles to return to their birthplace. That's the equivalent for a human of walking about a marathon and a half, without any signs or road maps. Scientists aren't sure exactly how they find their way, but they think it might be based on smell.

Why do newts live in a pond? California Newts live most of their time in the forest, but mate in the pond where they were born.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

The humble pine cone is more than a holiday decoration. It's an ancient form of tree sex. Flowers may be faster and showier, but the largest living things in the world? The oldest? They all reproduce with cones.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Do pine cones have seeds?

“There are two different types of cones,” says Bruce Baldwin, professor of plant biology at University of California, Berkeley. “There’s seed cones and pollen cones. The pollen cones are relatively tiny. The seed cone gets to be much larger and takes three years to develop and release seeds so you can often see pine cones of three different stages of development on a single tree.”

Why do pine cones open and close?

Early in their development, the scales open slightly for a short time to grant access to wind-borne pollen released from smaller pollen cones. After receiving the pollen, the female cones close back up until the seeds are fertilized and mature. Once they are, the scales reopen allowing the wind to disperse the winged seeds.

What are the oldest living trees?

Conifers are some of the oldest plants in the forest. And they were once much more diverse than they are today. But since the evolution of flowering plants, their diversity has plummeted. Today only about 0.3 percent of all the species of seed plants have cones. Flowering plants have taken over most of the warmer, wetter habitats, pushing out the evergreen conifers.

What are the tallest living trees?

The tallest (coast redwood), most massive (giant sequoia) and oldest living (bristlecone pine) individual organisms is the world are all conifers.

More great Deep Look episodes:

These 'Resurrection Plants' Spring Back to Life in Seconds | Deep Look:

https://youtu.be/eoFGKlZMo2g

The Hidden Perils of Permafrost:

https://youtu.be/wxABO84gol8

See also another great video from the PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay to Be Smart:

https://youtu.be/jgspUYDwnzQ

BrainCraft:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xr1dB86xE8o

Read an extended article on pine cones:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....015/11/24/the-sex-li

If you’re in the San Francisco Bay Area, You can check out the conifer collections at the University of California, Berkeley Jepson Herbarium:

http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/

Or take a stroll through Tilden Regional Parks Botanic Garden to see a variety of California conifers:

http://www.ebparks.org/page156.aspx

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Sure, the female black widow has a terrible reputation. But who’s the real victim here? Her male counterpart is a total jerk — and might just be getting what he deserves.

Learn more about CuriosityStream at http://curiositystream.com/deeplook

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

We’ve all heard the stories. She mates and then kills. Her venom is 15 times stronger than a rattlesnake’s. One bite could kill you. With a shiny black color and a glaring red hourglass stomach, she has long inspired fear and awe.

But most species of widow spider (there are 31), including the western black widow found in the U.S., don’t kill their mates at all. Only two widow spider species always eat their mate, the Australian redback and the brown widow, an invasive species in California.

And the male seems to be asking for it. In both of these species, he offers himself to her, somersaulting into her mouth after copulation.

He may even deserve it. During peak mating season, thousands of males will prowl around looking for females. Females set up their webs, stay put and wait.

Once the male arrives at her silken abode, he starts to wreck it, systematically disassembling her web one strand at a time. In a process scientists call web reduction, he bunches it into a little ball and wraps it up with his own silk.

Then, while mating, he will wrap her in fine strands that researchers refer to as the bridal veil. He drapes his silk over her legs, where her smell receptors are most concentrated.

After all of that, he is most likely to crawl away, alive and unscathed.

--- Why does the black widow spider eat her mate?

No one really knows, but scientists assume his body supplies her with nutrition for laying eggs. Sometimes she eats him by accident, not recognizing him as a mate.

--- How harmful are black widows to people?

We couldn’t find a documented case of a human death from a black widow spider in the U.S., but a bite will make you sick with extreme flu-like symptoms. Luckily, black widows aren’t aggressive to people.

--- Why do black widows have a red hourglass?

It’s a warning sign, a phenomenon common in nature that scientists call aposematicism, which is the use of color to ward off enemies.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....018/01/09/why-the-ma

---+ For more information:

Black widow researcher Catherine Scott’s website: http://spiderbytes.org/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Why Is The Very Hungry Caterpillar So Dang Hungry?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=el_lPd2oFV4

Everything You Never Wanted to Know About Snail Sex

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOcLaI44TXA

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Origin of Everything: Why Does Santa Wear Red?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fajNM5OPVnA

PBS Eons: 'Living Fossils' Aren't Really a Thing

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mPvZj2KcjAY

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate based in San Francisco, serves the people of Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial media. Home to one of the most listened-to public radio station in the nation, one of the highest-rated public television services and an award-winning education program, KQED is also a leader and innovator in interactive media and technology, taking people of all ages on journeys of exploration — exposing them to new people, places and ideas.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #blackwidow #spiders

Support Deep Look on Patreon!! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

The South American palm weevil is bursting onto the scene in California. Its arrival could put one of the state’s most cherished botanical icons at risk of oblivion.

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Summer means vacation time, and nothing says, “Welcome to paradise!” quite like a palm tree. Though it’s home to only one native species, California has nonetheless adopted the palm as a quintessential icon.

But a new snake in California’s palm tree-lined garden may soon put all that to the test. Dozens of palms in San Diego’s Sweetwater Summit Regional Park, about 10 miles from the Mexican border, are looking more like sad, upside-down umbrellas than the usual bursts of botanical joy.

The offender is the South American palm weevil, a recent arrival to the U.S. that’s long been widespread in the tropics. Large, black, shiny, and possessed of an impressive proboscis (nose), the weevil prefers the king of palms, the Canary Island date palm, also known as the “pineapple palm” for the distinctive way it’s typically pruned.

A palm tree is basically a gigantic cake-pop, an enormous ball of veggie goodness on a stick. The adult female palm weevil uses her long snout to drill tunnels into that goodness—known to science as the “apical meristem” and to your grocer as the “heart” of the palm—where she lays her eggs.

When her larvae hatch, their food is all around them. And they start to eat.

If the South American palm weevil consolidates its foothold in California, then the worst might still be to come. While these weevils generally stick to the Canary Island palms, they can harbor a parasitic worm that causes red-ring disease—a fatal infection that can strike almost any palm, including the state’s precious native, the California fan.

--- Where do South American Palm Weevils come from?

Originally, Brazil and Argentina. They’ve become common wherever there are Canary Island Palm trees, however, which includes Europe, the Mediterranean, the Middle East.

--- How do they kill palm trees?

Their larvae eat the apical meristem, which is the sweet part of the plant sometimes harvested and sold commercially as the “heart of palm.”

--- How do you get rid of them?

If the palm weevils infest a tree, it’s very hard to save it, since they live on the inside, where they escape both detection and pesticides. Neighboring palm trees can be sprayed for protection.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/06/20/a-real-ali

---+ For more information:

Visit the UC Riverside Center for invasive Species Research:

http://cisr.ucr.edu/invasive_species.html

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Decorator Crabs Make High Fashion at Low Tide

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OwQcv7TyX04

Everything You Never Wanted to Know About Snail Sex

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOcLaI44TXA

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Gross Science: Meet The Frog That Barfs Up Its Babies

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9xfX_NTrFRM

Brain Craft: Mutant Menu: If you could, would you design your DNA? And should you be able to?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NrDM6Ic2xMM

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #palmweevil

How long does it take to film a decorator crab putting on its seaweed hat? Hint: It's days, not hours. The Deep Look team is back with a second behind the scenes video! Get to know host Lauren Sommer and producers Gabriela Quiros, Josh Cassidy and Elliott Kennerson as we put together our episode on decorator crabs and reflect on the joys and challenges of making nature films.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

---+ Episodes Featured in this video:

The Snail-Smashing, Fish-Spearing, Eye-Popping Mantis Shrimp

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lm1ChtK9QDU

Everything You Never Wanted to Know About Snail Sex

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOcLaI44TXA

These Termites Turn Your House into a Palace of Poop

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DYPQ1Tjp0ew

Decorator Crabs Make High Fashion at Low Tide

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OwQcv7TyX04

Roly Polies Came From the Sea to Conquer the Earth

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sj8pFX9SOXE

Why Does Your Cat's Tongue Feel Like Sandpaper?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9h_QtLol75I

How Mosquitoes Use Six Needles to Suck Your Blood

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rD8SmacBUcU

The Bombardier Beetle And Its Crazy Chemical Cannon

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BWwgLS5tK80

This Pulsating Slime Mold Comes in Peace (ft. It's Okay to Be Smart)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nx3Uu1hfl6Q

Sea Urchins Pull Themselves Inside Out to be Reborn

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ak2xqH5h0YY

These 'Resurrection Plants' Spring Back to Life in Seconds

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eoFGKlZMo2g

Nature's Mood Rings: How Chameleons Really Change Color

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kp9W-_W8rCM

Pygmy Seahorses: Masters of Camouflage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3CtGoqz3ww

If Your Hands Could Smell, You’d Be an Octopus

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XXMxihOh8ps

How Do Pelicans Survive Their Death-Defying Dives?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BfEboMmwAMw

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

African elephants may have magnificent ears, but on the savanna, they communicate over vast distances by picking up underground signals with their sensitive, fatty feet.

You can learn more about CuriosityStream at https://curiositystream.com/deeplook.

Love Deep Look? Join us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Thousands of elephants roam Etosha National Park in Namibia, a nation in southwest Africa, taking turns at the park’s numerous watering holes. The elephants exchange information by emitting low-frequency sounds that travel dozens of miles under the ground on the savannah.

The sound waves come from the animals’ huge vocal chords, and distant elephants “hear” the signals with their highly sensitive feet. The sound waves spread out through the ground and air. By triangulating the two types of signals using both ears and feet, elephants can tune into the direction, distance and content of a message.

Seismic communication is the key to understanding the complex dynamics of elephant communities. There are seismic messages that are sent passively, such as when elephants eavesdrop on each others’ footsteps. More active announcements include alarm cries, mating calls and navigation instructions to the herd.

Seismic communication works with elephants because of the incredible sensitivity of their feet. Like all mammals, including humans, elephants have receptors called Pacinian corpuscles, or PCs, in their skin. PCs are hard-wired to a part of the brain where touch signals are processed, called the somatosensory cortex.

In elephants, PCs are clustered around the edge of the foot. When picking up a far-off signal, elephants sometimes press their feet into the ground, enlarging its surface by as much as 20 percent.

Strictly speaking, when elephants pick up ground vibrations in thei feet, it’s their sense of feeling, not hearing, at work. Typically hearing happens without physical contact, when airborne vibrations hit the eardrum, causing the tiny bones of the inner ear tremble and transmit a message to the brain along the auditory nerve.

But in elephants, some ground vibrations actually reach the hearing centers of the brain through a process called bone conduction.

By modeling how the elephant’s inner ear bones respond to seismic sound waves, scientists are hoping to use a bone-conduction approach develop new and better hearing aids for people. Instead of amplifying sound waves through the ear canal, these devices would transmit sound vibrations into a person’s jawbone or skull.

--- Where did you film this episode?

It was filmed in Etosha National Park in Namibia, at Menasha watering hole, which is closed to the public. We also filmed with the elephants at the Performing Animal Welfare Society (PAWS) sanctuary in San Andreas, Calif.

--- Do all elephants communicate seismically?

Both species of elephants – Asian and African – can pick up vibrations in their feet. There are some differences in anatomy between the two species, which cannot interbreed. Those include attributes related to their hearing, and probably arose as adaptations to their distinct habitats.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....018/07/17/how-elepha

---+ For more information:

Visit Caitlin O’Connell-Rodwell’s non-profit, Utopia Scientific. You could even go with her to Africa: http://www.utopiascientific.or....g/Research/mushara.h

Support the Performing Animal Welfare Society (PAWS): http://www.pawsweb.org

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

These Whispering, Walking Bats Are Onto Something

https://youtu.be/l2py029bwhA

For These Tiny Spiders, It's Sing or Get Served

https://youtu.be/y7qMqAgCqME

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the Templeton Religion Trust and the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #elephant #seismiccommunication

An onslaught of tiny western pine beetles can bring down a mighty ponderosa pine. But the forest fights back by waging a sticky attack of its own. Who will win the battle in the bark?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Bark beetles are specialized, with each species attacking only one or a few species of trees. Ponderosa pines are attacked by dark brown beetles the size of a grain of rice called western pine beetles (Dendroctonus brevicomis).

In the spring and summer, female western pine beetles fly around ponderosa pine stands looking for trees to lay their eggs in. As they start boring into a ponderosa, the tree oozes a sticky, viscous clear liquid called resin. If the tree is healthy, it can produce so much resin that the beetle gets exhausted and trapped as the resin hardens, which can kill it.

“The western pine beetle is an aggressive beetle that in order to successfully reproduce has to kill the tree,” said U.S. Forest Service ecologist Sharon Hood, based in Montana. “So the tree has very evolved responses. With pines, they have a whole resin duct system. You can imagine these vertical and horizontal pipes.”

But during California’s five-year drought, which ended earlier this year, ponderosa pines weren’t getting much water and couldn’t make enough resin to put up a strong defense. Beetles bored through the bark of millions of trees and sent out an aggregating pheromone to call more beetles and stage a mass attack. An estimated 102 million trees – most of them ponderosa – died in California between 2010 and 2016.

-- What is resin?

Resin – sometimes also called pitch – is a different substance from sap, though trees produce both. Resin is a sticky, viscous liquid that trees exude to heal over wounds and flush out bark beetles, said Sharon Hood, of the Forest Service. Sap, on the other hand, is the continuous water column that the leaves pull up to the top of the tree from its roots.

--- Are dead trees a fire hazard?

Standing dead trees that have lost their needles don’t increase fire risk, said forest health scientist Jodi Axelson, a University of California extension specialist based at UC Berkeley. But “once they fall to the ground you end up with these very heavy fuel loads,” she said, “and that undoubtedly is going to make fire behavior more intense.”

And dead – or living – trees can fall on electric lines and ignite a fire, which is why agencies in California are prioritizing the removal of dead trees near power lines, said Axelson.

---+ Read the entire article about who’s winning the battle between ponderosa pines and western pine beetles in California, on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/10/24/with-calif

---+ For more information:

Check out the USDA’s “Bark Beetles in California Conifers – Are Your Trees Susceptible?”

https://www.fs.usda.gov/Intern....et/FSE_DOCUMENTS/ste

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

This Mushroom Starts Killing You Before You Even Realize It

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bl9aCH2QaQY&t=57s

The Bombardier Beetle And Its Crazy Chemical Cannon

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BWwgLS5tK80

There’s Something Very Fishy About These Trees …

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rZWiWh5acbE

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

Vascular Plants = Winning! - Crash Course Biology #37

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h9oDTMXM7M8&index=37&list=PL3EED4C1D684D3ADF

Julia Child Remixed | Keep On Cooking

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=80ZrUI7RNfI

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Ladybugs spend most of their lives alone, gorging themselves on aphids. But every winter they take to the wind, soaring over cities and fields to assemble for a ladybug bash. In these huge gatherings, they'll do more than hibernate-it's their best chance to find a mate.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: an ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Read more on ladybugs:

http://ww2.kqed.org/science/20....16/02/09/the-once-in

Where do ladybugs live?

In California, ladybugs spend most of the year on crops in the Central Valley, or on domestic garden plants, feeding on aphids. When the weather starts to turn chilly, however, the aphids die off in the cold. With food becoming scarce, the ladybugs take off, flying straight up. The wind picks them up and carries them on their way, toward hills in the Bay Area and coastal mountain ranges.

What do ladybugs eat?

Ladybugs spend most of the year on crops or on domestic garden plants, feeding on aphids.

Are ladybugs insects?

Ladybugs belong to the order Coleoptera, or beetles. Europeans have called these dome-backed beetles by the name ladybirds, or ladybird beetles, for over 500 years. In America, the name ladybird was replaced by ladybug. Scientists usually prefer the common name lady beetles.

Why are some ladybugs red?

The red color is to signal to predators that they are toxic. "They truly do taste bad. In high enough concentrations, they can be toxic," said Christopher Wheeler, who studied ladybug behavior for his Ph.D. at UC Riverside.

More great Deep Look episodes on biology:

Where Are the Ants Carrying All Those Leaves?

https://youtu.be/-6oKJ5FGk24

Watch Flesh-Eating Beetles Strip Bodies to the Bone:

https://youtu.be/Np0hJGKrIWg

Nature's Scuba Divers: How Beetles Breathe Underwater:

https://youtu.be/T-RtG5Z-9jQ

See also another great video from the PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay to Be Smart: Why Seasons Make No Sense

https://youtu.be/s0oX9YJ5XLo

If you're in the San Francisco Bay Area, In the Bay Area, one of the best places to view ladybug aggregations is Redwood Regional Park in Oakland. Between November and February, numerous points along the park's main artery, the Stream Trail, are swarming with the insects.

http://www.ebparks.org/parks/redwood

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

How do we capture such amazing nature footage? Check out the making of "Sticky. Stretchy. Waterproof. The Amazing Underwater Tape of the Caddisfly." Watch producer Elliott Kennerson and cinematographer Josh Cassidy in action with UC Berkeley caddisfly expert Patina Mendez. Find out how they filmed these tiny creatures underwater and how they got the caddisflies to build their cases for the camera.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....016/08/16/behind-the

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

This Vibrating Bumblebee Unlocks a Flower's Hidden Treasure

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SZrTndD1H10

These Carnivorous Worms Catch Bugs by Mimicking the Night Sky

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vLb0iuTVzW0

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay to Be Smart: Venom: Nature’s Killer Cocktails

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qd92MuVZXik

Gross Science: Sea Turtles Get Herpes, Too

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bpqP9bUUInI

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Thanks to The Great Courses Plus for sponsoring this episode of Deep Look. Try a 30 day trial of The Great Course Plus at http://ow.ly/7QYH309wSOL. If you liked this episode, you might be interested in their course “Major Transitions in Evolution”.

POW! BAM! Fruit flies battling like martial arts masters are helping scientists map brain circuits. This research could shed light on human aggression and depression.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Neuroscientist Eric Hoopfer likes to watch animals fight. But these aren’t the kind of fights that could get him arrested – no roosters or pit bulls are involved.

Hoopfer watches fruit flies.

The tiny insects are the size of a pinhead, with big red eyes and iridescent wings. You’ve probably only seen them flying around an overripe piece of fruit.

At the California Institute of Technology, in Pasadena, Hoopfer places pairs of male fruit flies in tiny glass chambers. When they start fighting, they look like martial arts practitioners: They stand face to face and tip each other over; they lunge, roll around and even toss each other, sumo-wrestler style.

But this isn’t about entertainment. Hoopfer is trying to understand how the brain works.

When the aggressive fruit flies at Caltech fight, Hoopfer and his colleagues monitor what parts of their brains the flies are using. The researchers can see clusters of neurons lighting up. In the future, they hope this can help our understanding of conditions that tap into human emotional states, like depression or addiction.

“Flies when they fight, they fight at different intensities. And once they start fighting they continue fighting for a while; this state persists. These are all things that are similar to (human) emotional states,” said Hoopfer. “For example, there’s this scale of emotions where you can be a little bit annoyed and that can scale up to being very angry. If somebody cuts you off in traffic you might get angry and that lasts for a little while. So your emotion lasts longer than the initial stimulus.”

Circuits in our brains that make us stay mad, for example, could hold the key to developing better treatments for mental illness.

“All these neuro-psychiatric disorders, like depression, addiction, schizophrenia, the drugs that we have to treat them, we don’t really understand exactly how they are acting at the level of circuits in the brain,” said Hoopfer. “They help in some cases the symptoms that you want to treat. But they also cause a lot of side effects. So what we’d ideally like are drugs that can act on the specific neurons and circuits in the brain that are responsible for depression and for the symptoms of depression that we want to treat, and not ones that control other things.”

--- What do fruit flies eat?

In the lab, researchers feed fruit flies yeast and apple juice.

--- How do I get rid of fruit flies in my house?

Fruit flies are attracted to ripe fruit and vegetables.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/03/28/these-figh

---+ For more information:

The David Anderson Lab at Caltech:

https://davidandersonlab.caltech.edu/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

How Mosquitoes Use Six Needles to Suck Your Blood

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rD8SmacBUcU

Meet the Dust Mites, Tiny Roommates That Feast On Your Skin

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ACrLMtPyRM0

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It’s Okay To Be Smart: Why Your Brain Is In Your Head

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdNE4WygyAk

BrainCraft: Can You Solve This Dilemma?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9xHKxrc0PHg

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

The Great Courses Plus is currently available to watch through a web browser to almost anyone in the world and optimized for the US market. The Great Courses Plus is currently working to both optimize the product globally and accept credit card payments globally.

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, California, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Salmon make a perilous voyage upstream past hungry eagles and bears to mate in forest creeks. When the salmon die, a new journey begins – with maggots.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

For salmon lovers in California, October is “the peak of the return” when hundreds of thousands of Chinook salmon leave the open ocean and swim back to their ancestral streams to spawn and die. All along the Pacific coast, starting in the early summer and stretching as late as December, salmon wait offshore for the right timing to complete their journey inland.

In Alaska, the season starts in late June, when salmon head to streams in lush coastal forests. Although this annual migration is welcomed by fishermen who catch the salmon offshore, scientists are finding a much broader and holistic function of the spawning salmon: feeding the forest.

Millions of salmon make this migratory journey -- called running -- every year, and their silvery bodies all but obscure the rivers they pass through. This throng of salmon flesh coming into Alaska’s forests is a mass movement of nutrients from the salt waters of the ocean to the forest floor. Decomposing salmon on the sides of streams not only fertilize the soil beneath them, they also provide the base of a complex food web that depends upon them.

--- Why Do Salmon Swim Upstream?

Salmon run up freshwater streams and rivers to mate. A female salmon will dig a depression in the gravel with her tails and then deposit her eggs in the hole. Male salmon swim alongside the female and release a cloud of sperm at the same. The eggs are fertilized in the running water as the female buries them under a layer of gravel.

When the eggs hatch, they spend the first part of their lives hunting and growing in their home stream before heading out to sea to spend their adulthood.

--- Why Do Salmon Die After Mating?

Salmon typically mate once and then die, though some may return to the sea and come back to mate the subsequent year. Salmon put all of their energy into mating instead of maintaining the salmon’s body for the future. This is a type of mating strategy where adults die after a single mating episode is called semelparity.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/09/26/theres-som

---+ For more information:

Bob Armstrong’s Nature Alaska

http://www.naturebob.com/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

These Fish Are All About Sex on the Beach | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j5F3z1iP0Ic&list=PLdKlciEDdCQDxBs0SZgTMqhszst1jqZhp&index=3

Decorator Crabs Make High Fashion at Low Tide | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OwQcv7TyX04

Daddy Longlegs Risk Life ... and Especially Limb ... to Survive | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tjDmH8zhp6o

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Beavers: The Smartest Thing in Fur Pants | It’s Okay To Be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zm6X77ShHa8

How Do Glaciers Move? | It’s Okay To Be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RnlPrdMoQ1Y&t=165s

The Smell of Durian Explained | Reactions (ft. BrainCraft, Joe Hanson, Physics Girl & PBS Space Time)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a0v0n6tKPLc

How Do Glaciers Move? | It’s Okay To Be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RnlPrdMoQ1Y

Your Biological Clock at Work | BrainCraft

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Q8djfQlYwQ

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate based in San Francisco, serves the people of Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial media. Home to one of the most listened-to public radio station in the nation, one of the highest-rated public television services and an award-winning education program, KQED is also a leader and innovator in interactive media and technology, taking people of all ages on journeys of exploration — exposing them to new people, places and ideas.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

A deadly fungus is attacking frogs’ skin and wiping out hundreds of species worldwide. Can anyone help California's remaining mountain yellow-legged frogs? In a last-ditch effort, scientists are trying something new: build defenses against the fungus through a kind of frog “vaccine.”

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Chytrid fungus has decimated some 200 amphibian species around the world, among them the mountain yellow-legged frogs of California’s Sierra Nevada mountain range.

Frogs need healthy skin to survive. They breathe and drink water through it, and absorb the sodium and potassium their hearts need to work.

In the late 1970s, chytrid fungus started getting into mountain yellow-legged frogs through their skin, moving through the water in their alpine lakes, or passed on by other frogs. The fungus destroys frogs’ skin to the point where they can no longer absorb sodium and potassium. Eventually, they die.

At the University of California, Santa Barbara, biologists Cherie Briggs and Mary Toothman did an experiment to see if they could save mountain yellow-legged frogs by immunizing them against chytrid fungus.

They grew some frogs from eggs. Then they infected them with chytrid fungus. The frogs got sick. Their skin sloughed off, as happens typically to infected frogs. But before the fungus could kill the frogs, the researchers treated them with a liquid antifungal that stopped the disease.

When the frogs were nice and healthy again, researchers re-infected them with chytrid fungus. They found that all 20 frogs they had immunized survived. Now the San Francisco and Oakland zoos are replicating the experiment and returning dozens of mountain-yellow legged frogs to the Sierra Nevada’s alpine lakes.

--- How does chytrid fungus kill frogs?

Spores of chytrid fungus burrow down into frogs’ skin, which gets irritated. They run out of energy. Sick frogs’ legs lock in the straight position when they try to hop. As they get sicker, their skin sloughs off in translucent sheets. The frogs can no longer absorb sodium and potassium their hearts needs to function. “It takes 2-3 weeks for a yellow-legged frog to die from chytridiomycosis,” said mountain yellow-legged frog expert Vance Vredenburg , of San Francisco State University. “Eventually they die from a heart attack.”

--- How does chytrid fungus spread?

Fungus spores, which have a little tail called a flagellum, swim through the water and attack a frog’s skin. The fungus can also get passed on from amphibian to amphibian.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....016/09/06/can-a-new-

---+ For more information:

AmphibiaWeb

http://www.amphibiaweb.org/chy....trid/chytridiomycosi

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

These Crazy Cute Baby Turtles Want Their Lake Back

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YTYFdpNpkMY

Newt Sex: Buff Males! Writhing Females! Cannibalism!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5m37QR_4XNY

Sticky. Stretchy. Waterproof. The Amazing Underwater Tape of the Caddisfly

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z3BHrzDHoYo

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

It’s Okay To Be Smart: Do Plants Think?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zm6zfHzvqX4

Gross Science: Why Get Your Tetanus Shot?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O4jrqj5Dr8s

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

What does it mean to be blue? The wings of a Morpho butterfly are some of the most brilliant structures in nature, and yet they contain no blue pigment -- they harness the physics of light at the nanoscale. Learn more about these butterflies: http://goo.gl/dGo5XE

SUBSCRIBE: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

OK. Maybe you would. But the lengths they have to go to to stock up for the winter *will* surprise you. When you see how carefully they arrange each acorn, you might just need to reorganize your pantry.

You can learn more about CuriosityStream at https://curiositystream.com/deeplook.

Join Deep Look on Patreon NOW! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

You can learn more about CuriosityStream at https://curiositystream.com/deeplook .

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Have you ever wondered why woodpeckers pound so incessantly?

In the case of acorn woodpeckers – gregarious black and red birds in California’s oak forests – they’re building an intricate pantry, a massive, well-organized stockpile of thousands of acorns to carry them through the winter.

“They’re the only animals that I know of that store their acorns individually in holes in trees,” said biologist Walter Koenig, of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, who has studied acorn woodpeckers for decades at the University of California’s Hastings Natural History Reservation in Carmel Valley.

Over generations, acorn woodpeckers can drill thousands of small holes into one or several trees close to each other, giving these so-called granaries the appearance of Swiss cheese.

This sets them apart from other birds that drop acorns into already-existing cavities in trees, and animals like squirrels and jays that bury acorns in the ground.

In spring and summer, hikers in California commonly see acorn woodpeckers while the birds feed their chicks and care for their granaries. They don’t mind people staring at them and they’re easy to find. They greet each other with loud cries that sound like “waka-waka-waka.”

They’re also found in Oregon, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas, and all the way south to Colombia.

These avian performers are constantly tapping, drilling and pounding at their granaries.

“They’ll usually have a central granary, maybe two trees that a group is using,” said Koenig. “Those trees are going to be close together.”

Acorn woodpeckers make their granaries in pines, oaks, sycamores, redwoods and even in the palm trees on the Stanford University campus.

Their holes rarely hurt the trees. The birds only bore into the bark, where there’s no sap, or they make their granaries in snags.

“They don’t want sap in the hole because it will cause the acorn to rot,” said Koenig. “The point of storing the acorns is that it protects them from other animals getting them and it allows them to dry out.”

--- What is an acorn?

It’s the fruit of the oak.

--- Do acorn woodpeckers only eat acorns?

In the spring, acorn woodpeckers have their choice of food. They catch insects, eat oak flowers and suck the sap out of shallow holes on trees like coast live oaks.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....925251/youd-never-gu

---+ For more information:

Cornell Lab of Ornithology: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/....guide/Acorn_Woodpeck

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

What Gall! The Crazy Cribs of Parasitic Wasps

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lOgP5NzcTuA

How Ticks Dig in With a Mouth Full of Hooks

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_IoOJu2_FKE

Why is the Hungry Caterpillar So Dang Hungry?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=el_lPd2oFV4

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

Eons: Why Triassic Animals Were Just the Weirdest

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=moxu_uTemNg

Physics Girl: Why this skateboarding trick should be IMPOSSIBLE ft. Rodney Mullen

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yFRPhi0jhGc

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the Templeton Religion Trust and the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Male crickets play tunes non-stop to woo a mate or keep enemies away. But they're not playing their song with the body part you're thinking.

Please join our community on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

---

Ask most people about crickets and you’ll probably hear that they’re all pretty much the same: just little insects that jump and chirp.

But there are actually dozens of different species of field crickets in the U.S. And because they look so similar, the most common way scientists tell them apart is by the sounds they make.

“When I hear an evening chorus, all I hear are the different species,” said David Weissman, a research associate in entomology at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco.

Weissman has spent the last 45 years working to identify all the species of field crickets west of the Mississippi River. In December, he published his findings in the journal Zootaxa, identifying 35 species of field crickets in the western states, including 17 new species. California alone hosts 12 species. But many closely resemble the others. So even for one of the nation’s top experts, telling them apart isn’t a simple task.

“It turns out song is a good way to differentiate,” Weissman said.

--- How do crickets chirp?

On the underside of male crickets’ wings there’s a vein that sticks up covered in tiny microscopic teeth, all in a row. It’s called the file. There's a hard edge on the lower wing called the scraper.

When he rubs his wings together - the scraper on the bottom wing grates across all those little teeth on the top wing. It’s like running your thumb down the teeth of a comb. This process of making sound is called stridulation.

--- How do crickets hear?

Crickets have tiny ears, called tympana on each of their two front legs. They use them to listen for danger and to hear each other calling.

--- Why do crickets chirp?

Crickets have several different types of songs that serve different purposes. The familiar repetitive chirping song is a mating call that male crickets produce to attract females that search for potential mates.

If a female makes physical contact with a male he will typically switch to a second higher-pitched, quieter courtship song.

If instead a male cricket comes in contact with another adult male he will let out an angry-sounding rivalry call to tell his competitor to back off.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....020/01/14/crickets-c

---+ For more information:

Professor Fernando Montealegre-Z’s bioacoustics lab

http://bioacousticssensorybiology.weebly.com/

David Weissman’s article cataloging field crickets in the U.S.

https://www.biotaxa.org/Zootax....a/article/view/zoota

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to the following fans on our YouTube community tab for correctly identifying the name and function of the kidney bean-shaped structure on the cricket’s tibia - the tympanum, or tympanal organ:

sjhall2009

Damian Porter

LittleDreamerRem

Red Segui

Ba Ri

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Alice Kwok

Allen

Amber Miller

Aurora

Aurora Mitchell

Barbara Pinney

Bethany

Bill Cass

Blanca Vides

Burt Humburg

Caitlin McDonough

Carlos Carrasco

Chris B Emrick

Chris Murphy

Cindy McGill

Companion Cube

Daisuke Goto

Daniel Weinstein

David Deshpande

Dean Skoglund

Edwin Rivas

Egg-Roll

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

Geidi Rodriguez

Gerardo Alfaro

Guillaume Morin

Jane Orbuch

Joao Ascensao

johanna reis

John King

Johnnyonnyful

Josh Kuroda

Joshua Murallon Robertson

Justin Bull

Kallie Moore

Karen Reynolds

Katherine Schick

Kathleen R Jaroma

Kendall Rasmussen

Kristy Freeman

KW

Kyle Fisher

Laura Sanborn

Laurel Przybylski

Leonhardt Wille

Levi Cai

Louis O'Neill

luna

Mary Truland

monoirre

Natalie Banach

Nathan Wright

Nicolette Ray

Nikita

Noreen Herrington

Osbaldo Olvera

Pamela Parker

Richard Shalumov

Rick Wong

Robert Amling

Robert Warner

Roberta K Wright

Sarah Khalida Mohamad

Sayantan Dasgupta

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

Silvan Wendland

Sonia Tanlimco

SueEllen McCann

Supernovabetty

Syniurge

Tea Torvinen

TierZoo

Titania Juang

Trae Wright

Two Box Fish

WhatzGames

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.