Top Vídeos

synthpop 1986

a-ha

"The Weight Of The Wind"

Session Basel

Suíça, 2005

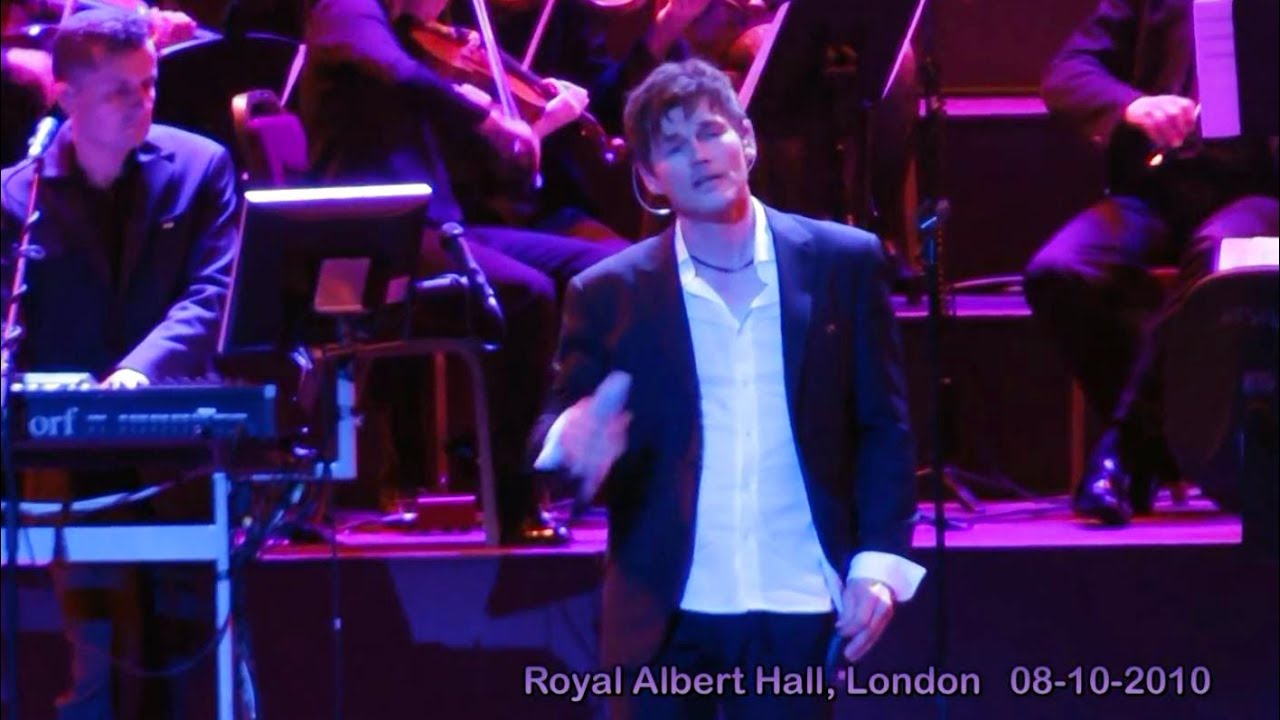

Performing their first 2 albums accompanied by the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra.

From a-ha's second album Scoundrel Days

From "Scoundrel Days" album

Del álbum "Scoundrel Days"

a-ha-uk performing live at a private function in Bakewell Nov 2013

from a-ha's second album "scoundrel Days" http://www.amazon.co.uk/Scound....rel-Days/dp/B001F4U2

Double Live Album http://www.amazon.co.uk/Sleep-Your-Voice-Double-Album/dp/B001F5W1RO/ref=sr_f3_2?ie=UTF8&s=dmusic&qid=1232319418&sr=103-2

Provided to YouTube by The Orchard Enterprises

weight of the wind · Chris Merola

Straight Answer In A Crooked Town

℗ 1999 Cropduster Records

Released on: 1999-06-29

Auto-generated by YouTube.

Summer Electric Tour!

This video is a Paul only! Although there might be some brilliant backing band members featuring too and an occasional drop in of other guys in the band!

A-ha - The weight of the wind - 25 July 2018 - Vienne (France)

The Weight Of The Wind de a-ha en live au Théâtre Antique de Vienne le 25/07/18.

Provided to YouTube by YouTube CSV2DDEX

The Weight Of Wind · Borknagar

Epic

℗ Century Media Records

Released on: 2004-06-17

Auto-generated by YouTube.

Álbum Scoundrel Days - 1986 Warner Bros.

A-ha - The Weight Of The Wind, Tivoli, Copenhagen 2018-07-27

My attempt at another a-ha classic!

♥️

https://www.discogs.com/master/view/11182

https://www.discogs.com/artist/37757-a-ha

BIO, MUSIC, LIKE & FOLLOW

https://www.linkedin.com/in/ariskapas

https://www.hearthis.at/djarisjr/

https://www.mixcloud.com/djarisjr/

https://www.clowdy.com/djarisjr

https://www.youtube.com/user/ariskapas

https://www.facebook.com/djarisjr

https://www.twitter.com/ariskapas

LYRICS :

This alone is love.

No small thing.

This alone is love,

that my love brings.

And all of us.

Who are traveling by trap-doors,

our souls are a myriad of wars.

And I'm losing everyone.

It will make my last breath pass out at dawn,

at dawn.

It will make my body dissolve out in the blue,

oh for you.

Oh baby, what can we do.