Animales y Mascotas

Artificial light makes the modern world possible. But not all kinds of light are good for us. Electric light has fundamentally altered our lives, our bodies and the very nature of our sleep.

SUBSCRIBE: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

It's an all-out brawl for prime beach real estate! These Caribbean crabs will tear each other limb from limb to get the best burrow. Luckily, they molt and regrow lost legs in a matter of weeks, and live to fight another day.

You can learn more about CuriosityStream at https://curiositystream.com/deeplook

Help Deep Look grow by supporting us on Patreon!!

https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

PBS Digital Studios Mega-playlist:

https://www.youtube.com/playli....st?list=PL1mtdjDVOoO

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

On the sand-dune beaches where they live, male blackback land crabs do constant battle over territory. The stakes are high: If one of these baby-faced crabs secures a winning spot, he can invite a mate into his den, six or seven feet beneath the surface.

With all this roughhousing, more than feelings get hurt. The male crabs inevitably lose limbs and damage their shells in constant dust-ups. Luckily, like many other arthropods, a group that includes insects and spiders, these crabs can release a leg or claw voluntarily if threatened. It’s not unusual to see animals in the field missing two or three walking legs.

The limbs regrow at the next molt, which is typically once a year for an adult. When a molt cycle begins, tiny limb buds form where a leg or a claw has been lost. Over the next six to eight weeks, the buds enlarge while the crab reabsorbs calcium from its old shell and secretes a new, paper-thin one underneath.

In the last hour of the cycle, the crab gulps air to create enough internal pressure to pop open the top of its shell, called the carapace. As the crab pushes it way out, the same internal pressure helps uncoil the new legs. The replacement shell thickens and hardens, and the crab eats the old shell.

--- Are blackback land crabs edible?

Yes, but they’re not as popular as the major food species like Dungeness and King crab.

--- Where do blackback land crabs live?

They live throughout the Caribbean islands.

--- Does it hurt when they lose legs?

Hard to say, but they do have an internal mechanism for releasing limbs cleanly that prevents loss of blood.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....933532/whack-jab-cra

---+ For more information:

The Crab Lab at Colorado State University:

https://rydberg.biology.colostate.edu/mykleslab/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Want a Whole New Body? Ask This Flatworm How

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m12xsf5g3Bo

Daddy Longlegs Risk Life ... and Especially Limb ... to Survive

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tjDmH8zhp6o

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Origin of Everything: The Origin of Gender

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5e12ZojkYrU

Hot Mess: Coral Reefs Are Dying. But They Don’t Have To.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MUAsFZuFQvQ

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the Templeton Religion Trust, the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

---+ Shoutout!

Congratulations to ?Jen Wiley?, who was the first to correctly ID the species of crab in our episode over at the Deep Look Community Tab:

https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UC-3SbfTPJsL8fJAPK

#deeplook #pbsds #crab

Not all roaches are filthy. The Madagascar hissing cockroach actually makes a pretty sweet pet, thanks to the hungry mites that serve as its cleaning crew.

Check out Antarctic Extremes on PBS Terra: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EvRAuy1ZmTc

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

---

As the weather starts to warm and cold days give way to balmier, sunny days, one rite of spring returns every year, just like spring flowers: cockroaches.

Most people run to buy a can of bug spray or to call the exterminator when they see the scurrying little insects in their kitchens or outside their homes.

But not all roaches are pests. Some are pets – like the Madagascar hissing cockroach.

They can be bought at pet stores or online for $5 or less. They don’t bite and don’t carry diseases. They are also much larger than the run-of-the-mill roach, with adults averaging about 3 inches long. They live up to five years. They are slow-moving and mellow – kind of like an old tabby cat. But with antennae. And an appetite for fresh vegetables.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....955611/you-wish-you-

--- Why do the cockroaches hiss?

They’ll hiss when they’re sounding an alarm or startled, trying to attract a mate or protecting their territory from another male.

--- Are the mites harmful to the cockroaches?

No – they actually help prolong the cockroaches’ lives.

--- What happens to the mites if its host cockroach dies?

The mites will mate, give birth to their young and feed on the same cockroach their entire lives – so they’ll usually die within a few days after the cockroach dies, too, and not seek a new home.

---+ For more information:

UC Davis Bohart Museum of Entomology

http://bohart.ucdavis.edu/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

It’s a Bug’s Life: https://www.youtube.com/playli....st?list=PLdKlciEDdCQ

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to the following fans on our YouTube community tab who correctly identified the creature from a past episode most closely related to cockroaches - the termite!

Keroro407

John Marvin Accad

Battledroid0521

Tiny Stash

Jeanne Cabral

Termites are basically social roaches. More info:

https://gizmodo.com/termites-a....re-finally-being-rec

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Amber Miller

Aurora

Aurora Mitchell

Bethany

Bill Cass

Blanca Vides

Burt Humburg

Caitlin McDonough

Carlos Carrasco

Chris B Emrick

Chris Murphy

Cindy McGill

Companion Cube

Daisuke Goto

Daniel Weinstein

David Deshpande

Dean Skoglund

Edwin Rivas

Egg-Roll

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

Geidi Rodriguez

Gerardo Alfaro

Guillaume Morin

Jane Orbuch

Joao Ascensao

johanna reis

John King

Johnnyonnyful

Josh Kuroda

Joshua Murallon Robertson

Justin Bull

Kallie Moore

Karen Reynolds

Katherine Schick

Kathleen R Jaroma

Kendall Rasmussen

Kristy Freeman

KW

Kyle Fisher

Laura Sanborn

Laurel Przybylski

Leonhardt Wille

Levi Cai

Louis O'Neill

luna

Mary Truland

monoirre

Natalie Banach

Nathan Wright

Nicolette Ray

Nikita

Noreen Herrington

Osbaldo Olvera

Pamela Parker

Richard Shalumov

Rick Wong

Robert Amling

Robert Warner

Roberta K Wright

Sarah Khalida Mohamad

Sayantan Dasgupta

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

Silvan Wendland

Sonia Tanlimco

SueEllen McCann

Supernovabetty

Syniurge

Tea Torvinen

TierZoo

Titania Juang

Trae Wright

Two Box Fish

WhatzGames

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, the largest science and environment reporting unit in California. KQED Science is supported by The National Science Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

#hissingcockroaches #insect #deeplook

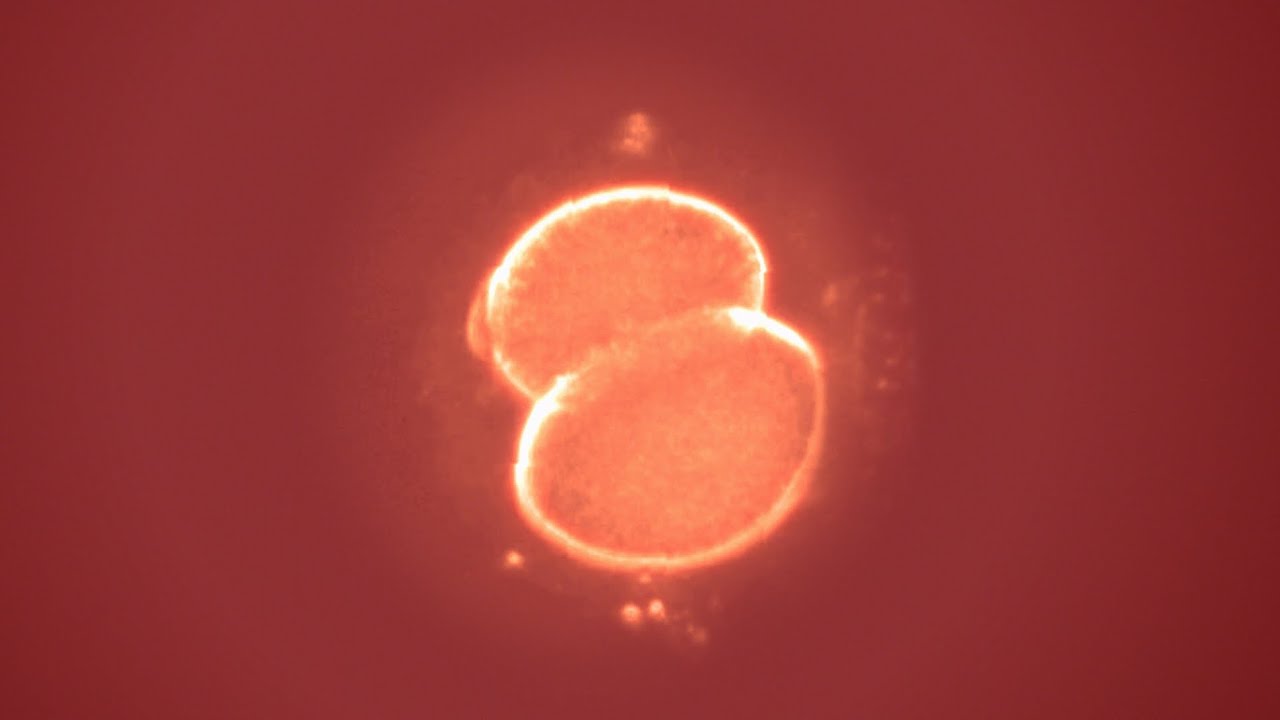

Every one of us started out as an embryo, but only a few early embryos – about one in three – grow into a baby. Researchers are unlocking the mysteries of our embryonic clock and helping patients who are struggling to get pregnant.

SUBSCRIBE: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Those hundreds of powerful suckers on octopus arms do more than just stick. They actually smell and taste. This contributes to a massive amount of information for the octopus’s brain to process, so octopuses depend on their eight arms for help. (And no, it's not 'octopi.')

To keep up with Amy Standen, subscribe to her podcast The Leap - a podcast about people making dramatic, risky changes:

https://ww2.kqed.org/news/programs/the-leap/

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Everyone knows that an octopus has eight arms. And similar to our arms it uses them to grab things and move around. But that’s where the similarities end. Hundreds of suckers on each octopus arm give them abilities people can only dream about.

“The suckers are hands that also smell and taste,” said Rich Ross, senior biologist and octopus aquarist at the California Academy of Sciences.

Suckers are “very similar to our taste buds, from what little we know about them,” said University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, cephalopod biologist William Kier.

If these tasting, smelling suckers make you think of a human hand with a tongue and a nose stuck to it, that’s a good start. It all stems from the unique challenges an octopus faces as a result of having a flexible, soft body.

“This animal has no protection and is a wonderful meal because it’s all muscle,” said Kier.

So the octopus has adapted over time. It has about 500 million neurons (dogs have around 600 million), the cells that allow it to process and communicate information. And these neurons are distributed to make the most of its eight arms. An octopus’ central brain – located between its eyes – doesn’t control its every move. Instead, two thirds of the animal’s neurons are in its arms.

“It’s more efficient to put the nervous cells in the arm,” said neurobiologist Binyamin Hochner, of Hebrew University, in Jerusalem. “The arm is a brain of its own.”

This enables octopus arms to operate somewhat independently from the animal’s central brain. The central brain tells the arms in what direction and how fast to move, but the instructions on how to reach are embedded in each arm.

Octopuses have also evolved mechanisms that allow their muscles to move without the use of a skeleton. This same muscle arrangement enables elephant trunks and mammals’ tongues to unfurl.

“The arrangement of the muscle in your tongue is similar to the arrangement in the octopus arm,” said Kier.

In an octopus arm, muscles are arranged in different directions. When one octopus muscle contracts, it’s able to stretch out again because other muscles oriented in a different direction offer resistance – just as the bones in vertebrate bodies do. This skeleton of muscle, called a muscular hydrostat, is how an octopus gets its suckers to attach to different surfaces.

--- How many suction cups does an octopus have on each arm?

It depends on the species. Giant Pacific octopuses have up to 240 suckers on each arm.

--- Do octopuses have arms or tentacles?

Octopuses have arms, not tentacles. “The term ‘tentacle’ is used for lots of fleshy protuberances in invertebrates,” said Kier. “It just happens that the eight in octopuses are called arms.”

--- Can octopuses regrow a severed arm?

Yes!

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/02/14/if-your-ha

---+ For more information:

The octopus research group at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gN81dtxilhE

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

You're Not Hallucinating. That's Just Squid Skin.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0wtLrlIKvJE

Watch These Frustrated Squirrels Go Nuts!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZUjQtJGaSpk

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It’s Okay To Be Smart: Is This A NEW SPECIES?!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=asZ8MYdDXNc

BrainCraft: Your Brain in Numbers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FFcbnf07QZ4

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Support Deep Look on Patreon!! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Because it's hoarding protein. Not just for itself, but for the butterfly it will become and every egg that butterfly will lay. And it's about to lose its mouth... as it wriggles out of its skin during metamorphosis.

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

That caterpillar in your backyard is chewing through your best leaves for a good reason.

“Caterpillars have to store up incredible reserves of proteins,” said Carol Boggs, an ecologist at the University of South Carolina. “Nectar doesn’t have much protein. Most of the protein that goes to making eggs has to come from larval feeding.”

Caterpillars are the larval stage of a butterfly. Their complete transformation to pupa and then to butterfly is a strategy called holometaboly. Humans are in the minority among animals in that we don’t go through these very distinct, almost separate, lives. We start out as a smaller version of ourselves and grow bigger.

But from an evolutionary point of view, the way butterflies transform make sense.

“You have a larva that is an eating machine,” said Boggs. “It’s very well-suited to that. Then you’re turning it into a reproduction machine, the butterfly.”

Once it becomes a butterfly it will lose its mouth, grow a straw in its place and go on a liquid diet of sugary nectar and rotten fruit juices. Its main job will be to mate and lay eggs. Those eggs started to develop while it was a pupa, using protein that the caterpillar stored by gorging on leaves. We think of leaves as carbohydrates, but the nitrogen they contain makes them more than one quarter protein, said Boggs.

-- What are the stages of a butterfly?

Insects such as butterflies undergo a complete transformation, referred to by scientists as holometaboly. A holometabolous insect has a morphology in the juvenile state which is different from that in the adult and which undergoes a period of reorganization between the two, said Boggs. The four life stages are egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa (also known as chrysalis) and butterfly.

-- What if humans developed like butterflies?

“We’d go into a quiescent period when we developed different kind of eating organs and sensory organs,” said Boggs. “It would be as if we went into a pupa and developed straws as mouths and developed more elaborate morphology for smelling and developed wings. It brings up science fiction images.”

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/07/11/why-is-the

---+ For more information:

Monarch Watch: http://www.monarchwatch.org

California Pipevine Swallowtail Project:

https://www.facebook.com/Calif....orniaPipevineSwallow

A forum organized by Tim Wong, who cares for the butterflies in the California Academy of Sciences’ rainforest exhibit. Wong’s page has beautiful photos and videos of California pipevine swallowtail butterflies at every stage – caterpillar, pupa and butterfly – and tips to create native butterfly habitat.

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

What Gives the Morpho Butterfly Its Magnificent Blue?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=29Ts7CsJDpg

This Vibrating Bumblebee Unlocks a Flower's Hidden Treasure

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SZrTndD1H10

Roly Polies Came From the Sea to Conquer the Earth

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sj8pFX9SOXE

In the Race for Life, Which Human Embryos Make It?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9mv_kuwQvoc

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

PBS Eons: When Did the First Flower Bloom?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=13aUo5fEjNY

CrashCourse: The History of Life on Earth - Crash Course Ecology #1

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sjE-Pkjp3u4

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #caterpillars #butterflies

Support Deep Look on Patreon!! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

The notorious death cap mushroom causes poisonings and deaths around the world. If you were to eat these unassuming greenish mushrooms by mistake, you wouldn’t know your liver is in trouble until several hours later. The death cap has been spreading across California. Can scientists find a way to stop it?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Find out more on KQED Science:

http://ww2.kqed.org/science/20....16/02/23/this-mushro

Where do death cap mushrooms grow?

In California, they grow mainly under coast live oaks. They have also been found under pines, and in Yosemite Valley under black oaks.

Why do death caps grow under trees?

As many fungi do, death cap mushrooms live off of trees, in what’s called a mycorrhizal relationship. They send filaments deep down to the trees’ roots, where they attach to the very thin root tips. The fungi absorb sugars from the trees and give them nutrients in exchange.

Where do California’s death cap mushrooms come from?

Biologist Anne Pringle, at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, has done research that shows that death caps likely snuck into California from Europe attached to the roots of imported plants, as early as 1938.

How deadly are death cap mushrooms?

Between 2010 and 2015, five people died in California and 57 became sick after eating the unassuming greenish mushrooms, according to the California Poison Control System. One mushroom cap is enough to kill a human being, and they’re also poisonous to dogs. Death caps are believed to be the number one cause of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide.

What happens if you eat a death cap mushroom?

A toxin in the mushroom destroys your liver cells. Dr. Kent Olson, co-medical director of the San Francisco Division of the California Poison Control System, said that for the first six to 12 hours after they eat the mushroom, victims of the death cap feel fine. During that time, a toxin in the mushroom is quietly injuring their liver cells. Patients then develop severe abdominal pain, diarrhea and vomiting. “They can become very rapidly dehydrated from the fluid losses,” said Olson. Dehydration can cause kidney failure, which compounds the damage to the liver. For the most severe cases, the only way to save the patient is a liver transplant.

For more information on the death cap:

Bay Area Mycological Society’s page with photos: http://bayareamushrooms.org/mu....shroommonth/amanita_

Rod Tulloss’ detailed description: http://www.amanitaceae.org/?Amanita%20phalloides

More great Deep Look episodes:

What Happens When You Zap Coral With The World's Most Powerful X-ray Laser?

https://youtu.be/aXmCU6IYnsA

These 'Resurrection Plants' Spring Back to Life in Seconds

https://youtu.be/eoFGKlZMo2g

See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay to Be Smart: Your Salad Is Trying To Kill You

https://youtu.be/8Ofgj2KDbfk

It's Okay to Be Smart: The Oldest Living Things In The World

https://youtu.be/jgspUYDwnzQ

For more content from your local PBS and NPR affiliate:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #mushroom #deathcap

Mammalian moms, you're not alone! A female tsetse fly pushes out a single squiggly larva almost as big as herself, which she nourished with her own milk.

Please join our community on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

---

Mammalian moms aren’t the only ones to deliver babies and feed them milk. Tsetse flies, the insects best known for transmitting sleeping sickness, do it too.

A researcher at the University of California, Davis is trying to understand in detail the unusual way in which these flies reproduce in order to find new ways to combat the disease, which has a crippling effect on a huge swath of Africa.

When it’s time to give birth, a female tsetse fly takes less than a minute to push out a squiggly yellowish larva almost as big as itself. The first time he watched a larva emerge from its mother, UC Davis medical entomologist Geoff Attardo was reminded of a clown car.

“There’s too much coming out of it to be able to fit inside,” he recalled thinking. “The fact that they can do it eight times in their lifetime is kind of amazing to me.”

Tsetse flies live four to five months and deliver those eight offspring one at a time. While the larva is growing inside them, they feed it milk. This reproductive strategy is extremely rare in the insect world, where survival usually depends on laying hundreds or thousands of eggs.

--- What is sleeping sickness?

Tsetse flies, which are only found in Africa, feed exclusively on the blood of humans and other domestic and wild animals. As they feed, they can transmit microscopic parasites called trypanosomes, which cause sleeping sickness in humans and a version of the disease known as nagana in cattle and other livestock. Sleeping sickness is also known as human African trypanosomiasis.

--- What are the symptoms of sleeping sickness?

The disease starts with fatigue, anemia and headaches. It is treatable with medication, but if trypanosomes invade the central nervous system they can cause sleep disruptions and hallucinations and eventually make patients fall into a coma and die.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....956004/a-tsetse-fly-

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

“Parasites Are Dynamite” Deep Look playlist:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C2Jw5ib-s_I&list=PLdKlciEDdCQACmrtvWX7hr7X7Zv8F4nEi

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to these fans on our YouTube community tab who correctly identified the function of the black protuberances on a tsetse fly larva - polypneustic lobes:

Jeffrey Kuo

Lizzie Zelaya

Art3mis YT

Garen Reynolds

Torterra Grey8

Despite looking like a head, they’re actually located at the back of the larva, which used them to breathe while growing inside its mother. The larva continues to breathe through the lobes as it develops underground.

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Alice Kwok

Allen

Amber Miller

Aurora

Aurora Mitchell

Bethany

Bill Cass

Blanca Vides

Burt Humburg

Caitlin McDonough

Cameron

Carlos Carrasco

Chris B Emrick

Chris Murphy

Cindy McGill

Companion Cube

Daisuke Goto

Daniel Weinstein

David Deshpande

Dean Skoglund

Edwin Rivas

Egg-Roll

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

Geidi Rodriguez

Gerardo Alfaro

Guillaume Morin

Jane Orbuch

Joao Ascensao

johanna reis

Johnnyonnyful

Josh Kuroda

Joshua Murallon Robertson

Justin Bull

Kallie Moore

Karen Reynolds

Katherine Schick

Kathleen R Jaroma

Kendall Rasmussen

Kristy Freeman

KW

Kyle Fisher

Laura Sanborn

Laurel Przybylski

Leonhardt Wille

Levi Cai

Louis O'Neill

luna

Mary Truland

monoirre

Natalie Banach

Nathan Wright

Nicolette Ray

Noreen Herrington

Osbaldo Olvera

Pamela Parker

Richard Shalumov

Rick Wong

Robert Amling

Robert Warner

Roberta K Wright

Sarah Khalida Mohamad

Sayantan Dasgupta

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

Silvan Wendland

Sonia Tanlimco

SueEllen McCann

Supernovabetty

Syniurge

Tea Torvinen

TierZoo

Titania Juang

Trae Wright

Two Box Fish

WhatzGames

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

#tsetsefly #sleepingsickness #deeplook

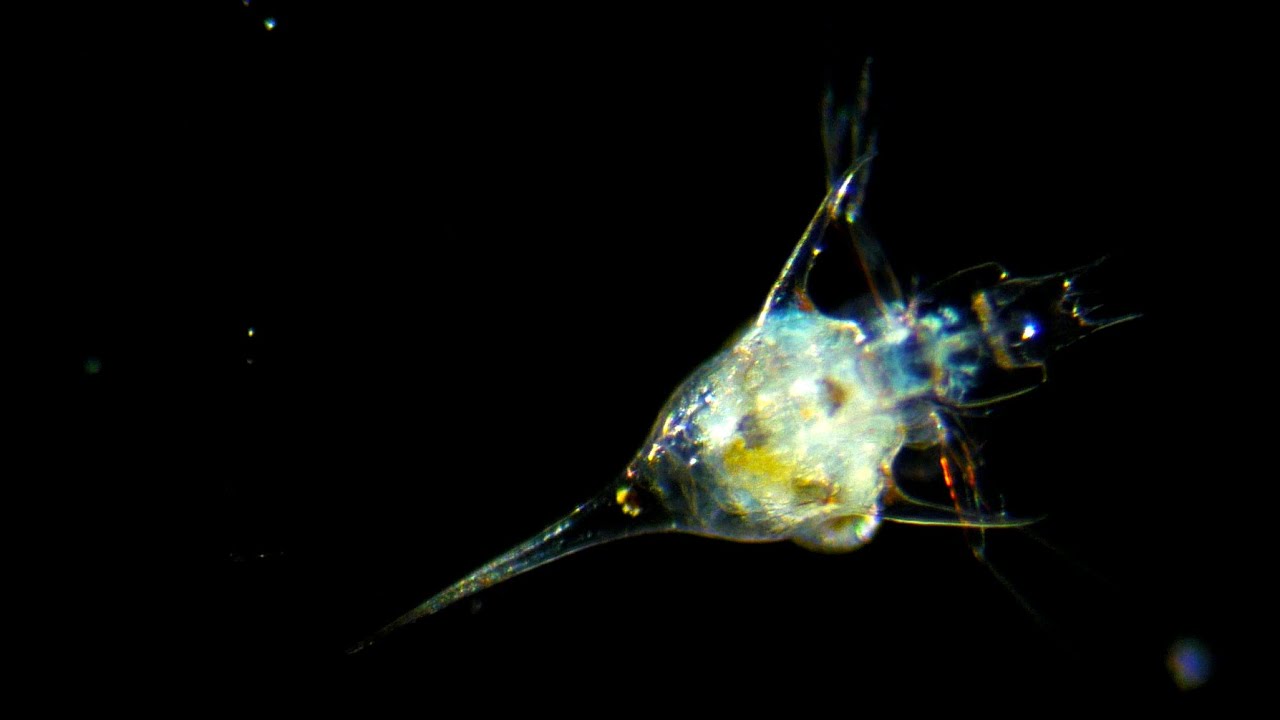

Most plankton are tiny drifters, wandering in a vast ocean. But where wind and currents converge they become part of a grander story … an explosion of vitality that affects all life on Earth, including our own.

SUBSCRIBE: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

For thousands of years, mysterious bacteria have remained dormant in the Arctic permafrost. Now, a warming climate threatens to bring them back to life. What does that mean for the rest of us?

SUBSCRIBE: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

What if you had to grow 20 pounds of bone on your forehead each year just to find a mate? In a bloody, itchy process, males of the deer family grow a new set of antlers every year, use them to fend off the competition, and lose their impressive crowns when breeding season ends.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* WE’RE TAKING A BREAK FOR THE HOLIDAYS. WATCH OUR NEXT EPISODE ON JAN. 17, 2017. *

Antlers are bones that grow right out of an animal’s head. It all starts with little knobs called pedicles. Reindeer, elk, and their relatives in the cervid family, like moose and deer, are born with them. But in most species pedicles only sprout antlers in males, because antlers require testosterone.

The little antlers of a young tule elk, or a reindeer, are called spikes. Every year, a male grows a slightly larger set of antlers, until he becomes a “senior” and the antlers start to shrink.

While it’s growing, the bone is hidden by a fuzzy layer of skin and fur called velvet that carries blood rich in calcium and phosphorous to build up the bone inside.

When the antlers get hard, the blood stops flowing and the velvet cracks. It gets itchy and males scratch like crazy to get it off. From underneath emerges a clean, smooth antler.

Males use their antlers during the mating season as a warning to other males to stay away from females, or to woo the females. When their warnings aren’t heeded, they use them to fight the competition.

Once the mating season is over and the male no longer needs its antlers, the testosterone in its body drops and the antlers fall off. A new set starts growing almost right away.

--- What are antlers made of?

Antlers are made of bone.

--- What is antler velvet?

Velvet is the skin that covers a developing antler.

--- What animals have antlers?

Male members of the cervid, or deer, family grow antlers. The only species of deer in which females also grow antlers are reindeer.

--- Are antlers horns?

No. Horns, which are made of keratin (the same material our nails are made from), stay on an animal its entire life. Antlers fall off and grow back again each year.

---+ Read an article on KQED Science about how neuroscientists are investigating the potential of the nerves in antler velvet to return mobility to damaged human limbs, and perhaps one day even help paralyzed people:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....016/12/06/rudolphs-a

---+ For more information on tule elk

https://www.nps.gov/pore/learn/nature/tule_elk.htm

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

The Sex Lives of Christmas Trees

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xEji9I4Tcjo

Watch These Frustrated Squirrels Go Nuts!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZUjQtJGaSpk

This Mushroom Starts Killing You Before You Even Realize It

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bl9aCH2QaQY

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

The REAL Rudolph Has Bloody Antlers and Super Vision - Gross Science

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gB6ND8nXgjA

Global Weirding with Katharine Hayhoe: Texans don't care about climate change, right?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P_r_6D2LXVs&list=PL1mtdjDVOoOqJzeaJAV15Tq0tZ1vKj7ZV&index=25

It’s Okay To Be Smart: Why Don’t Woodpeckers Get Concussions?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bqBxbMWd8O0

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

You might suppose this catfish is sick, or just confused. But swimming belly-up actually helps it camouflage and breathe better than its right-side-up cousins.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Normally, an upside-down fish in your tank is bad news. As in, it’s time for a new goldfish.

That’s because most fish have an internal air sac called a “swim bladder” that allows them to control their buoyancy and orientation. They fill the bladder with air when they want to rise, and deflate it when they want to sink. Fish without swim bladders, like sharks, have to swim constantly to keep from dropping to the bottom.

If an aquarium fish is listing to one side or flops over on its back, it often means it has swim bladder disease, a potentially life-threatening condition usually brought on parasites, overfeeding, or high nitrate levels in the water.

But for a few remarkable fish, being upside-down means everything is great.

In fact, seven species of catfish native to Central Africa live most of their lives upended. These topsy-turvy swimmers are anatomically identical to their right-side up cousins, despite having such an unusual orientation.

People’s fascination with the odd alignment of these fish goes back centuries. Studies of these quizzical fish have found a number of reasons why swimming upside down makes a lot of sense.

In an upside-down position, fish produce a lot less wave drag. That means upside-down catfish do a better job feeding on insect larvae at the waterline than their right-side up counterparts, who have to return to deeper water to rest.

There’s something else at the surface that’s even more important to a fish’s survival than food: oxygen. The gas essential to life readily dissolves from the air into the water, where it becomes concentrated in a thin layer at the waterline — right where the upside-down catfish’s mouth and gills are perfectly positioned to get it.

Scientists estimate that upside-down catfishes have been working out their survival strategy for as long at 35 million years. Besides their breathing and feeding behavior, the blotched upside-down catfish from the Congo Basin has also evolved a dark patch on its underside to make it harder to see against dark water.

That coloration is remarkable because it’s the opposite of most sea creatures, which tend to be darker on top and lighter on the bottom, a common adaptation called “countershading” that offsets the effects of sunlight.

The blotched upside-down catfish’s “reverse” countershading has earned it the scientific name negriventris, which means black-bellied.

--- How many kinds of fish swim upside down?

A total of seven species in Africa swim that way. Upside-down swimming may have evolved independent in a few of the species – and at least one more time in a catfish from Asia.

--- How do fish stay upright?

They have an air-filled swim bladder on the inside that that they can fill or deflate to maintain balance or to move up or down in the water column.

--- What are the benefits of swimming upside down?

Upside down, a fish swims more efficiently at the waterline, where there’s more oxygen and better access to some prey.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....922038/the-mystery-o

---+ For more information:

The California Academy of Sciences has upside-down catfish in its aquarium collection: https://www.calacademy.org/exh....ibits/steinhart-aqua

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Take Two Leeches and Call Me in the Morning

https://youtu.be/O-0SFWPLaII

This Is Why Water Striders Make Terrible Lifeguards

https://youtu.be/E2unnSK7WTE

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

PBS Eons: What a Dinosaur Looks Like Under a Microscope

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4rvgiDXc12k

Origin of Everything: The Origin of Race in the USA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CVxAlmAPHec

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

How does a group of animals -- or cells, for that matter -- work together when no one’s in charge? Tiny swarming robots--called Kilobots--work together to tackle tasks in the lab, but what can they teach us about the natural world?

↓ More info, videos, and sources below ↓

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

More KQED SCIENCE:

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science: http://ww2.kqed.org/science

About Kilobots

How do you simultaneously control a thousand robots in a swarm? The question may seem like science fiction, but it’s one that has challenged real robotics engineers for decades.

In 2010, the Kilobot entered the scene. Now, engineers are programming these tiny independent robots to cooperate on group tasks. This research could one day lead to robots that can assemble themselves into machines, or provide insights into how swarming behaviors emerge in nature.

In the future, this kind of research might lead to collaborative robots that could self-assemble into a composite structure. This larger robot could work in dangerous or contaminated areas, like cleaning up oil spills or conducting search-and-rescue activities.

What is Emergent Behavior?

The universe tends towards chaos, but sometimes patterns emerge, like a flock of birds in flight. Like termites building skyscrapers out of mud, or fish schooling to avoid predators.

It’s called emergent behavior. Complex behaviors that arise from interactions between simple things. And you don’t just see it in nature.

What’s so interesting about kilobots is that individually, they’re pretty dumb.

They’re designed to be simple. A single kilobot can do maybe... three things: Respond to light. Measure a distance, sense the presence of other kilobots.

But these are swarm robots. They work together.

How do Kilobots work?

Kilobots were designed by Michael Rubenstein, a research scientist in the Self Organizing Systems Research Group at Harvard. Each robot consists of about $15 worth of parts: a microprocessor that is about as smart as a calculator, sensors for visible and infrared light, and two tiny cell-phone vibration units that allow it to move across a table. They are powered by a rechargeable lithium-ion battery, like those found in small electronics or watches.

The kilobots are programed all at once, as a group, using infrared light. Each kilobot gets the same set of instructions as the next. With just a few lines of programming, the kilobots, together, can act out complex natural processes.

The same kinds of simple instructions that kilobots use to self-assemble into shapes can make them mimic natural swarming behaviors, too. For example, kilobots can sync their flashing lights like a swarm of fireflies, differentiate similar to cells in an embryo and follow a scent trail like foraging ants.

Read the article for this video on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....015/07/21/can-a-thou

More great DEEP LOOK episodes:

Where Are the Ants Carrying All Those Leaves?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-6oKJ5FGk24

What Happens When You Put a Hummingbird in a Wind Tunnel?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JyqY64ovjfY

Pygmy Seahorses: Masters of Camouflage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3CtGoqz3ww

Related videos from the PBS Digital Studios Network!

Is Ultron Inevitable? | It’s Okay to Be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Irmtk5QG8s

A History Of Robots | The Good Stuff

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TK-h4oATYSI

When Will We Worry About the Well-Being of Robots? | Idea Channel https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FLieeAUQWMs

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Alfalfa leafcutting bees are way better at pollinating alfalfa flowers than honeybees. They don’t mind getting thwacked in the face by the spring-loaded blooms. And that's good, because hungry cows depend on their hard work to make milk.

Join our community on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Please take our annual PBSDS Survey, for a chance to win a T-shirt! https://www.pbsresearch.org/c/r/DL_YTvideo

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

---

Sure, cows are important. But next time you eat ice cream, thank a bee.

Every summer, alfalfa leafcutting bees pollinate alfalfa in an intricate process that gets them thwacked by the flowers when they release the pollen that allows the plants to make seeds. The bees’ hard work came to fruition last week when growers in California finished harvesting the alfalfa seeds that will be grown to make nutritious hay for dairy cows.

This is how it works.

To produce alfalfa seeds, farmers let their plants grow until they bloom. They need help pollinating the tiny purple flowers, so that the female and male parts of the flower can come together and produce fertile seeds. That’s where the grayish, easygoing alfalfa leafcutting bees come in. Seed growers in California release the bees – known simply as cutters – in June and they work hard for a month.

Alfalfa’s flowers keep their reproductive organs hidden away inside a boat-shaped bottom petal called the keel petal, which is held closed by a thin membrane that creates a spring mechanism.

Cutter bees come up to the flower looking for nectar and pollen to feed on. When they land on the flower, the membrane holding the keel petal breaks and the long reproductive structure pops right up and smacks the upper petal or the bee, releasing its yellow pollen. This process is called “tripping the flower.”

When the flower is tripped, pollen falls on its female reproductive organ and fertilizes it; bees also carry pollen away on their hairy bodies and help fertilize other flowers. In a few weeks, each flower turns into a curly pod with seven to 10 seeds growing inside.

Cutters trip 80 percent of flowers they visit, compared to honeybees, which only trip about 10 percent.

---

--- What kind of a plant is alfalfa?

Alfalfa is a legume, like beans and chickpeas. Other legumes also hold their reproductive organs within a keel petal.

--- What do bees use leaves for?

Alfalfa leafcutting bees and other leafcutter bees cut leaf and petal pieces to build their nest inside a hole, such as a nook and cranny in a log. Alfalfa farmers provide bees with holes in styrofoam boards.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....946996/this-bee-gets

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to the following fans for correctly identifying the bee body part coated in pollen, on our Leafcutting Bee - the scopa or scopae!

Punkonthego

GamingCuzWhyNot

Galatians 4:16

Gil AGA

Edison Lewis

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Leonhardt Wille

Justin Bull

Bill Cass

Sarah Khalida Mohamad

Daniel Weinstein

Chris B Emrick

Karen Reynolds

Tea Torvinen

David Deshpande

Daisuke Goto

Companion Cube

WhatzGames

Richard Shalumov

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

Gerardo Alfaro

Robert Amling

Shirley Washburn

Robert Warner

Supernovabetty

johanna reis

Kendall Rasmussen

Pamela Parker

Sayantan Dasgupta

Joshua Murallon Robertson

Cindy McGill

Kenia Villegas

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

Aurora

Dean Skoglund

Silvan Wendland

Ivan Alexander

monoirre

Sonia Tanlimco

Two Box Fish

Jane Orbuch

Allen

Laurel Przybylski

Johnnyonnyful

Rick Wong

Levi Cai

Titania Juang

Nathan Wright

Carl

Michael Mieczkowski

Kyle Fisher

JanetFromAnotherPlanet

Kallie Moore

SueEllen McCann

Geidi Rodriguez

Louis O'Neill

Edwin Rivas

Jeanne Sommer

Katherine Schick

Aurora Mitchell

Cory

Ricardo Martinez

riceeater

Daisy Trevino

KW

PM Daeley

Joao Ascensao

Chris Murphy

Nicolette Ray

TierZoo

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

#leafcutter #bees #deeplook

Beneath the towering redwoods lives one of the most peculiar creatures in California: the banana slug. They're coated with a liquid crystal ooze that solves many problems slugs face in the forest -- and maybe some of our own.

SUBSCRIBE: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Banana slugs are important members of the redwood forest community, even if they aren't the most exalted. They eat animal droppings, leaves and other detritus on the forest floor, and then generate waste that fertilizes new plants. Being slugs, they don't move very quickly, and without a shell, they need other protection to keep themselves from becoming food and then fertilizer. Their main defense: slime. Slime refers to mucus-the same stuff that coats your nose and lungs-found on the outside of an animal's body. Banana slug slime contains nasty chemicals that numb the tongue of any animal that attempts to nibble it, discouraging predators like raccoons, who have to go to the trouble of removing the slime if they want to eat the slug. But this is just one of many ways slugs depend on slime, and they use it for everything from locomotion to nutrition.

Read more in our article on KQED Science:

http://blogs.kqed.org/science/....2015/02/17/banana-sl

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Join Deep Look on Patreon NOW!

https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

They may be dressed in black, but crow funerals aren't the solemn events that we hold for our dead. These birds cause a ruckus around their fallen friend. Are they just scared, or is there something deeper going on?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

It’s a common site in many parks and backyards: Crows squawking. But groups of the noisy black birds may not just be raising a fuss, scientists say. They may be holding a funeral.

Kaeli Swift, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Washington’s Avian Conservation Lab in Seattle, is studying how crows learn about danger from each other and how they respond to seeing one of their own who has died.

Unlike the majority of animals, crows react strongly to seeing a fellow member of their species has died, mobbing together and raising a ruckus.

Only a few animals like whales, elephants and some primates, have such strong reactions.

To study exactly what may be going on on, Swift developed an experiment that involved exposing local crows in Seattle neighborhoods to a dead taxidermied crow in order to study their reaction.

“It’s really incredible,” she said. “They’re all around in the trees just staring at you and screaming at you.”

Swift calls these events ‘crow funerals’ and they are the focus of her research.

--- What do crows eat?

Crows are omnivores so they’ll eat just about anything. In the wild they eat insects, carrion, eggs seeds and fruit. Crows that live around humans eat garbage.

--- What’s the difference between crows and ravens?

American crows and common ravens may look similar but ravens are larger with a more robust beak. When in flight, crow tail feathers are approximately the same length. Raven tail feathers spread out and look like a fan.

Ravens also tend to emit a croaking sound compared to the caw of a crow. Ravens also tend to travel in pairs while crows tend to flock together in larger groups. Raven will sometimes prey on crows.

--- Why do crows chase hawks?

Crows, like animals whose young are preyed upon, mob together and harass dangerous predators like hawks in order to exclude them from an area and protect their offspring. Mobbing also teaches new generations of crows to identify predators.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....923458/youve-heard-o

---+ For more information:

Kaeli Swift’s Corvid Research website

https://corvidresearch.blog/

University of Washington Avian Conservation Laboratory

http://sefs.washington.edu/research.acl/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Why Do Tumbleweeds Tumble? | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dATZsuPdOnM

Upside-Down Catfish Doesn't Care What You Think | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eurCBOJMrsE

Take Two Leeches and Call Me in the Morning | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O-0SFWPLaII

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

Why Climate Change is Unjust | Hot Mess

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q5KjpYK12_c

Is Breakfast the Most Important Meal? | Origin Of Everything

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AxIOGqHQqZM

How the Squid Lost Its Shell | PBS Eons

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S4vxoP-IF2M

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the Templeton Religion Trust and the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Male jumping spiders perform courtship dances that would make Bob Fosse proud. But if they bomb, they can wind up somebody's dinner instead of their mate.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

During courtship, the male jumping spider performs an exuberant dance to get the female’s attention. Like a pint-sized Magic Mike working for twenties, he shimmies from side to side, waves his legs, and flaps his front appendages (called pedipalps) in her direction.

If she likes what she sees, the female may allow him to mate. But things can also go terribly wrong for these eight-legged suitors. She might decide to attack him, or even eat him for lunch. Cannibalism is the result about seven percent of the time.

These mating rituals were first described more than 100 years ago. Their study took on a new dimension, however, when scientists discovered that the males also sing when they attempt to woo their lady loves.

By rubbing together their two body segments, equipped with a comb-shaped instrument, the males create vibrations that travel through the ground. The female spiders can “hear” the male songs through ear-like slits in their legs, called sensilla.

A male spider’s coordination of the dance and the song seems to affect his reproductive success — in other words, his ability to stay alive during this risky courtship trial. But what exactly the signals mean remains mysterious to scientists.

Scientists ultimately hope to understand how a female decides whether she’s looking at a stud — or a dud.

--- Where do jumping spiders get their name?

Jumping spiders don’t spin webs to catch food. They stalk their prey like cats. They use their silk as a drag line while they hop around.

--- What do jumping spiders eat?

Jumping spiders are carnivorous and eat insects like flies, bees, and crickets.

--- Where do jumping spiders live?

A map of jumping spider habitat looks like the whole world! Tropical forests contain the greatest number, but they live just about everywhere, even the Himalayan Mountains.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....016/10/04/for-these-

---+ For more information:

Elias Lab at U.C. Berkeley: https://nature.berkeley.edu/eliaslab/

---+ More great Deep Look episodes:

This Vibrating Bumblebee Unlocks a Flower's Hidden Treasure

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SZrTndD1H10

The Ladybug Love-In: A Valentine's Special

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c-Z6xRexbIU

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Idea Channel: Do You Pronounce it GIF or GIF?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bmqy-Sp0txY

Gross Science: Are There Dead Wasps In Figs?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9DQTjv_u3Vc

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Support Deep Look on Patreon!! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

(FYI - This episode is a *bit* more bloody that usual – especially a little after the 2-minute mark. Just letting you know in case flesh wounds aren’t your thing)

The same blood-sucking leeches feared by hikers and swimmers are making a comeback... in hospitals. Once used for questionable treatments, leeches now help doctors complete complex surgeries to reattach severed body parts.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Leeches get a bad rap—but they might not deserve it. Yes, they’re creepy crawly blood-suckers. And they can instill an almost primal sense of disgust and revulsion. Humphrey Bogart’s character in the 1951 film The African Queen even went so far as to call them “filthy little devils.”

But the humble leech is making a comeback. Contrary to the typical, derogatory definition of a human “leech,” this critter is increasingly playing a key role as a sidekick for scientists and doctors, simply by being its bloodthirsty self.

Distant cousins of the earthworm, most leech species are parasites that feed on the blood of animals and humans alike. They are often found in freshwater and navigate either by swimming or by inching themselves along, using two suckers—one at each end of their body—to anchor themselves.

Upon reaching an unsuspecting host, a leech will surreptitiously attach itself and begin to feed. It uses a triangular set of three teeth to cut in, and secretes a suite of chemicals to thin the blood and numb the skin so its presence goes undetected.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science: https://www.kqed.org/science/1....921659/take-two-leec

---+ For more information:

David Weisblat at UC Berkeley studies leeches development and evolution

https://mcb.berkeley.edu/labs/....weisblat/research.ht

Biologists recently reported that leeches in that region can provide a valuable snapshot of which animals are present in a particular area

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14772000.2018.1433729?journalCode=tsab20&

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Why the Male Black Widow is a Real Home Wrecker | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NpJNeGqExrc

For Pacific Mole Crabs It's Dig or Die | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tfoYD8pAsMw

Praying Mantis Love is Waaay Weirder Than You Think | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NHf47gI8w04&t=83s

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios! Above the Noise:

Cow Burps Are Warming the Planet | Reactions

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MnRFUSGz_ZM

What a Dinosaur Looks Like Under a Microscope | Eons

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4rvgiDXc12k

Hawking Radiation | Space Time

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qPKj0YnKANw

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Support Deep Look on Patreon!! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Scientists have used a high-speed camera to film hummingbirds' aerial acrobatics at 1000 frames per second. They can see, frame by frame, how neither wind nor rain stop these tiniest of birds from fueling up.

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

How do hummingbirds eat?

With spring in full bloom, hummingbirds can be spotted flitting from flower to flower and lapping up the sugary nectar inside. These tiniest of birds have the highest metabolism of any warm-blooded animal, requiring them to consume their own body weight in nectar each day to survive.

By comparison, if a 150-pound human had the metabolism of a hummingbird, he or she would need to consume the caloric equivalent of more than 300 hamburgers a day.

But it's not just an extreme appetite that sets hummingbirds apart from other birds. These avian acrobats are the only birds that can fly sideways, backwards and hover for long stretches of time. In fact, hovering is essential to hummingbirds' survival since they have to keep their long, thin beaks as steady as a surgeon's scalpel while probing flowers for nectar.

How do Hummingbirds fly?

Hummingbirds don't just hover to feed when the weather is nice. They have to keep hovering and feeding even if it's windy or raining, a remarkable feat considering most of these birds weigh less than a nickel.

More great Deep Look episodes:

Newt Sex: Buff Males! Writhing Females! Cannibalism!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5m37QR_4XNY

Pygmy Seahorses: Masters of Camouflage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3CtGoqz3ww

Banana Slugs: Secret of the Slime

https://youtu.be/mHvCQSGanJg

--

See also another great video from the PBS Digital Studios!

Where Do Birds Go In Winter? - It's Okay to be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ds2XFvSQzBg

Read the extended article on how hummingbirds hover at KQED Science:

http://blogs.kqed.org/science/....2015/03/31/what-happ

SUBSCRIBE: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

KQED Science: http://kqed.org/science

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #hummingbirds #wings

When predators attack, daddy longlegs deliberately release their limbs to escape. They can drop up to three and still get by just fine.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

We all know it’s not nice to pull the legs off of bugs.

Daddy longlegs don’t wait for that to happen. These arachnids, related to spiders, drop them deliberately. A gentle pinch is enough to trigger an internal system that discharges the leg. Whether it hurts is up for debate, but most scientists think not, given the automatic nature of the defense mechanism.

It’s called autotomy, the voluntary release of a body part.

Two of their appendages have evolved into feelers, which leaves the other six legs for locomotion. Daddy longlegs share this trait with insects, and have what scientists call the “alternate tripod gate,” where three legs touch the ground at any given point.

That elegant stride is initially hard-hit by the loss of a leg. In the daddy longlegs’ case, the lost leg doesn’t grow back.

But they persevere: A daddy longlegs that is one, two, or even three legs short can recover a surprising degree of mobility by learning to walk differently. And given time, the daddy longlegs can regain much of its initial mobility on fewer legs.

Once these adaptations are better understood, they may have applications in the fields of robotics and prosthetic design.

--- Are daddy longlegs a type of spider?

No, though they are arachnids, as spiders are. Daddy longlegs are more closely related to scorpions.

--- How can I tell a daddy longlegs from a spider?

Daddy longlegs have one body segment (like a pea), while spiders have two (like a peanut). Also, you won’t find a daddy longlegs in a web, since they don’t make silk.

--- Can a daddy longlegs bite can kill you?

Daddy longlegs are not venomous. And despite what you’ve heard about their mouths being too small, they could bite you, but they prefer fruit.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/08/22/daddy-long

---+ For more information:

Visit the Elias Lab at UC Berkeley:

https://nature.berkeley.edu/eliaslab/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Stinging Scorpion vs. Pain-Defying Mouse | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w-K_YtWqMro

For These Tiny Spiders, It's Sing or Get Served | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y7qMqAgCqME

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Gross Science: What Happens When You Get Rabies?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eiUUpF1UPJc

Physics Girl: Mantis Shrimp Punch at 40,000 fps! - Cavitation Physics

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m78_sOEadC8

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate based in San Francisco, serves the people of Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial media. Home to one of the most listened-to public radio station in the nation, one of the highest-rated public television services and an award-winning education program, KQED is also a leader and innovator in interactive media and technology, taking people of all ages on journeys of exploration — exposing them to new people, places and ideas.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #daddylonglegs #harvestman