Animales y Mascotas

There are strange little towers on the forest floor. Neat, right? Nope. Inside hides a spider that's cunning, patient and ruthless.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Please follow us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Most Bay Area hikers pass right by without ever noticing, but a careful eye can spot tiny towers rising up from the forest floor. These mysterious little tubes, barely an inch high, are the homes of a particularly sneaky predator -- the California turret spider.

“To me, the turrets look just like the rook in a chess set,” said Trent Pearce, a naturalist for the East Bay Regional Park District, as he scanned the terrain at Briones Regional Park. “The spiders themselves are super burly – like a tiny tarantula the size of your pinky nail.”

Turret spiders build their towers along creek beds and under fallen trees in forested areas throughout Central and Northern California. They use whatever mud, moss, bark and leaves they can find nearby, making their turrets extremely well camouflaged.

They line the inside of their tiny castles with pearly white silk, which makes the structure supple and resilient

Each turret leads down to a burrow that can extend six inches underground. The spiders spend their days down there in the dark, protected from the sun and predators.

As night falls, they climb up to the entrance of the turrets to wait for unsuspecting prey like beetles to happen by.

Turret spiders are ambush hunters. While remaining hidden inside their turret, they’re able to sense the vibrations created by their prey’s footsteps.

That’s when the turret spider strikes, busting out of the hollow tower like an eight legged jack-in-the-box. With lightning speed the spider swings its fangs down like daggers, injecting venom into its prey before dragging it down into the burrow.

“It’s like the scene in a horror movie where the monster appears out of nowhere – you can’t not jump,” Pearce said.

--- What do turret spiders eat?

Turret spiders mostly ground-dwelling arthropods like beetles but they will also attack flying insects like moths that happen to land near their turrets.

--- Are turret spiders dangerous to people?

Turret spiders are nocturnal so it’s rare for them to interact with humans by accident. They tend to retreat into their underground burrow if they feel the vibrations of human footsteps. They do have fangs and venom but are not generally considered to be dangerous compared to other spiders. If you leave them alone, you shouldn’t have anything to fear from turret spiders.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....019/01/15/turret-spi

---+ For more information:

Learn to Look for Them, and California’s Unique “Turret Spiders” are Everywhere

https://baynature.org/article/....and-this-little-spid

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

For These Tiny Spiders, It's Sing or Get Served | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/y7qMqAgCqME

Praying Mantis Love is Waaay Weirder Than You Think | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/EHo_9wnnUTE

Why the Male Black Widow is a Real Home Wrecker | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/NpJNeGqExrc

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

---+ Shoutout!

Congratulations to ?Iset4, MidKnight Fall7,

jon pomeroy, Justin Felder3, and DrowsyTaurus26?, who were the first to correctly ID the species of spider in our episode - Antrodiaetus riversi (also known as Atypoides riversi) over at the Deep Look Community Tab:

https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UC-3SbfTPJsL8fJAPK

(hat tip to Edison Lewis10 for posting the entire family tree!)

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the Templeton Religion Trust, the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation and the members of KQED. #deeplook #spiders #wildlife

Kangaroo rats use their exceptional hearing and powerful hind legs to jump clear of rattlesnakes — or even deliver a stunning kick in the face.

Please join our community on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

---

As they forage, kangaroo rats need to continually scan the surrounding sandy environment for any predators – foxes, owls, and snakes – that could be anywhere. Once a well-camouflaged sidewinder rattlesnake strikes, aiming its venomous fangs at the furry seed-harvester, the kangaroo rat springs up, and away from the snake’s deadly bite, kicking its powerful hind legs at the snake’s face, and using its long tail to twist itself in mid-air away from the snake to safety.

Kangaroo have the uncanny ability to jump high at just the right moment. Biologists believe that this most likely comes from its keen hearing, which is 90 times more sensitive than human ears, allowing the rats to react in as little as 50 milliseconds.

In addition to their finely-tuned ears, the desert kangaroo rats’ highly-evolved musculature generates lots of force very quickly, resulting in jumps almost ten times their body height.

Muscles in kangaroo rats have a thick tendon, surrounded by large muscles, which translates directly to more power and a faster reaction time. With its powerful hind limbs, the kangaroo rat is also able to deliver a “black belt” kick to the jaw of the rattlesnake, sending the rattlesnake soaring to the ground, before landing away from the snake.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....957226/kangaroo-rats

--- Can a kangaroo rat survive without water in the desert?

The body of the kangaroo rat has evolved to be especially adapted to their harsh dry desert environments, so they are able to get all of their water from seeds they eat.

--- How high can a kangaroo rat jump?

Some kangaroo rats are able to jump as high as 9 feet, or approximately 10 times their body height.

--- Are kangaroo rats endangered?

There are 20 existing species of kangaroo rats. Six of these species are considered threatened. The two species featured in our episode, the Merriam’s kangaroo rat (Dipodomys merriami) and desert kangaroo rat (Dipodomys deserti) are not endangered, and relatively common in the desert areas they are found.

---+ For more amazing slow motion videos of kangaroo rats and rattlesnakes, visit our friends at: https://www.ninjarat.org/

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to these fans on our YouTube community tab who identified the special parts in a kangaroo rats' skull that make their hearing so exceptional... the tympanic or auditory bullae:

Lights, Camera, Ants

Rohit Kumar Reddy Reddy

Eric Fung

Hotaru

otakuman706

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Amber Miller

Aurora

Aurora Mitchell

Bethany

Bill Cass

Blanca Vides

Burt Humburg

Caitlin McDonough

Carlos Carrasco

Chris B Emrick

Chris Murphy

Cindy McGill

Companion Cube

Daisuke Goto

Daniel Weinstein

David Deshpande

Dean Skoglund

Edwin Rivas

Egg-Roll

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

Geidi Rodriguez

Gerardo Alfaro

Guillaume Morin

Jane Orbuch

Joao Ascensao

johanna reis

John King

Johnnyonnyful

Josh Kuroda

Joshua Murallon Robertson

Justin Bull

Kallie Moore

Karen Reynolds

Katherine Schick

Kathleen R Jaroma

Kendall Rasmussen

Kristy Freeman

KW

Kyle Fisher

Laura Sanborn

Laurel Przybylski

Leonhardt Wille

Levi Cai

Louis O'Neill

luna

Mary Truland

monoirre

Natalie Banach

Nathan Wright

Nicolette Ray

Nikita

Noreen Herrington

Osbaldo Olvera

Pamela Parker

Richard Shalumov

Rick Wong

Robert Amling

Robert Warner

Roberta K Wright

Sarah Khalida Mohamad

Sayantan Dasgupta

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

Silvan Wendland

Sonia Tanlimco

SueEllen McCann

Supernovabetty

Syniurge

Tea Torvinen

TierZoo

Titania Juang

Trae Wright

Two Box Fish

WhatzGames

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, the largest science and environment reporting unit in California. KQED Science is supported by The National Science Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

#kangaroorat #rattlesnake #deeplook

The silent star of classic Westerns is a plant on a mission. It starts out green and full of life. It even grows flowers. But to reproduce effectively it needs to turn into a rolling brown skeleton.

You can learn more about CuriosityStream at https://curiositystream.com/deeplook.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Tumbleweeds might be the iconic props of classic Westerns. But in real life, they’re not only a noxious weed, but one that moves around. Pushed by gusts of wind, they can overwhelm entire neighborhoods, as happened recently in Victorville, California, or become a threat for drivers and an expensive nuisance for farmers.

“They tumble across highways and can cause accidents,” said Mike Pitcairn, who tracks tumbleweeds at the California Department of Food and Agriculture in Sacramento. “They pile up against fences and homes.”

And tumbleweeds aren’t even originally from the West.

Genetic tests have shown that California’s most common tumbleweed, known as Russian thistle, likely came from Ukraine, said retired plant population biologist Debra Ayres, who studied tumbleweeds at the University of California, Davis.

A U.S. Department of Agriculture employee, L. H. Dewey, wrote in 1893 that Russian thistle had arrived in the U.S. through South Dakota in flaxseed imported from Europe in the 1870s.

“It has been known in Russia many years,” Dewey wrote, “and has quite as bad a reputation in the wheat regions there as it has in the Dakotas.” This is where the name Russian thistle originates, said Ayres, although tumbleweeds aren’t thistles.

The weed spread quickly through the United States — on rail cars, through contamination of agricultural seeds and by tumbling.

“They tumble to disperse the seeds,” said Ayres, “and thereby reduce competition.”

A rolling tumbleweed spreads out tens of thousands of seeds so that they all get plenty of sunlight and space.

Tumbleweeds grow well in barren places like vacant lots or the side of the road, where they can tumble unobstructed and there’s no grass, which their seedlings can’t compete with.

--- Where does a tumbleweed come from?

Tumbleweeds start out attached to the soil. Seedlings, which look like blades of grass, sprout at the end of winter. By summer, Russian thistle plants take on their round shape and grow flowers. Inside each flower, a fruit with a seed develops.

Other plants attract animals with tasty fruits, and get them to carry away their seeds and disperse them when they poop.

Tumbleweeds developed a different evolutionary strategy. Starting in late fall, they dry out and die, their seeds nestled between prickly leaves. Gusts of wind easily break dead tumbleweeds from their roots and they roll away, spreading their seeds as they go.

--- How big do tumbleweeds grow?

Mike Pitcairn, of the California Department of Food and Agriculture, said that in the state’s San Joaquin Valley they can grow to be more than 6 feet tall.

--- Are tumbleweeds dangerous?

Yes. They can cause traffic accidents or be a fire hazard if they pile up near buildings.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....922987/why-do-tumble

---+ For more information on the history and biology of Russian thistle, here’s a paper by Debra Ayres and colleagues:

https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/28657/PDF

---+ More great Deep Look episodes:

How Ticks Dig In With a Mouth Full of Hooks

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_IoOJu2_FKE

This Giant Plant Looks Like Raw Meat and Smells Like Dead Rat

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ycUNj_Hv4_Y

Upside-Down Catfish Doesn't Care What You Think

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eurCBOJMrsE

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Above the Noise: Why Is Vaping So Popular?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P9zps5LsVXs

Hot Mess: What Happened to Nuclear Power?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_jEXZZDU6Gk

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the Templeton Religion Trust and the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Giant Malaysian leaf insects stay still – very still – on their host plants to avoid hungry predators. But as they grow up, they can't get lazy with their camouflage. They change – and even dance – to blend in with the ever-shifting foliage.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Please support us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

---

You’ll have to look closely to spot a giant Malaysian leaf insect when it’s nibbling on the leaves of a guava or mango tree. These herbivores blend in seamlessly with their surroundings because they look exactly like their favorite food: fruit leaves.

But you can definitely see these fascinating creatures at the California Academy of Sciences, located in the heart of San Francisco's Golden Gate Park, through the spring of 2022.

An ongoing interactive exhibit, ‘Color of Life,’ explores the role of color in the natural world. It's filled with a variety of critters, including Gouldian finches, green tree pythons, Riggenbach's reed frogs, and of course, giant leaf insects.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....947830/these-giant-l

--- What do giant leaf insects eat?

They’re herbivores, so they stick to eating leaves from their habitats, like guava and mango.

--- What’s one main difference between male and female giant leaf insects?

Males can actually fly as they have wings, which they use for mating.

--- But did you know that females don’t need males for mating?

They are facultatively parthenogenetic, which means they sometimes mate or sometimes reproduce asexually. If they mate with a male, they produce both males and females, but if the eggs remain unfertilized – only females are produced.

---+ For more information:

Visit California Academy of Sciences

https://calacademy.org/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

It’s a Bug’s Life: https://www.youtube.com/playli....st?list=PLdKlciEDdCQ

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to the following fans on our YouTube community tab for correctly identifying the type of reproduction female leaf insects can use in the absence of a suitable male - parthenogenesis.

Sylly

Jim Spencer

Rikki Anne

Cara Rose

GOT7 HOT7 THOT7 VISUAL7

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Trae Wright

Justin Bull

Bill Cass

Alice Kwok

Sarah Khalida Mohamad

Stefficael Uebelhart

Daniel Weinstein

Chris B Emrick

Seghan Seer

Karen Reynolds

Tea Torvinen

David Deshpande

Daisuke Goto

Amber Miller

Companion Cube

WhatzGames

Richard Shalumov

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

Robert Amling

Gerardo Alfaro

Mary Truland

Shirley Washburn

Robert Warner

johanna reis

Supernovabetty

Kendall Rasmussen

Sayantan Dasgupta

Cindy McGill

Leonhardt Wille

Joshua Murallon Robertson

Pamela Parker

Roberta K Wright

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

KW

Silvan Wendland

Two Box Fish

Johnnyonnyful

Aurora

George Koutros

monoirre

Dean Skoglund

Sonia Tanlimco

Guillaume Morin

Ivan Alexander

Laurel Przybylski

Allen

Jane Orbuch

Rick Wong

Levi Cai

Titania Juang

Nathan Wright

Syniurge

Carl

Kallie Moore

Michael Mieczkowski

Kyle Fisher

Geidi Rodriguez

JanetFromAnotherPlanet

SueEllen McCann

Daisy Trevino

Jeanne Sommer

Louis O'Neill

riceeater

Katherine Schick

Aurora Mitchell

Cory

Nousernamepls

Chris Murphy

PM Daeley

Joao Ascensao

Nicolette Ray

TierZoo

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

#leafinsects #insect #deeplook

Support Deep Look on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Dogs have a famously great sense of smell, but what makes their noses so much more powerful than ours? They're packing some sophisticated equipment inside that squishy schnozz.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

--- How much more powerful is a dog’s sense of smell compared to a human?

According to one estimate, dogs are 10,000-100,000 times more sensitive to smell than humans. They have about 15 times more olfactory neurons that send signals about odors to the brain. The neurons in a dog’s nose are spread out over a much larger and more convoluted area allowing them more easily decipher specific chemicals in the air.

--- Why are dog noses wet?

Dog noses secrete mucus which traps odors in the air and on the ground. When a dog licks its nose, the tongue brings those odors into the mouth allowing it to sample those smells. Dogs mostly cool themselves by panting but the mucus on their noses and sweat from their paws cool through evaporation.

--- Why do dog nostrils have slits on the side?

Dogs sniff about five times per second. The slits on the sides allows exhaled air to vent towards the sides and back. That air moving towards the back of the dog creates a low air pressure region in front of it. Air from in front of the dog rushes in to fill that low pressure region. That allows the nose to actively bring odors in from in front and keeps the exhaled air from contaminating new samples.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....019/02/26/how-your-d

---+ For more information:

The Odor Navigation Project funded NSF Brain Initiative

https://odornavigation.org/

Jacobs Lab of Cognitive Biology at UC Berkeley

http://jacobs.berkeley.edu/

Ecological Fluid Dynamics Lab at University of Colorado Boulder

https://www.colorado.edu/lab/ecological-fluids/

The fluid dynamics of canine olfaction: unique nasal airflow patterns as an explanation of macrosmia (Brent A. Craven, Eric G. Paterson, and Gary S. Settles)

https://royalsocietypublishing.....org/doi/full/10.109

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

The Fantastic Fur of Sea Otters | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zxqg_um1TXI

You've Heard of a Murder of Crows. How About a Crow Funeral? | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ixYVFZnNl6s&t=85s

Newt Sex: Buff Males! Writhing Females! Cannibalism! | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5m37QR_4XNY

What Makes Owls So Quiet and So Deadly? | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a68fIQzaDBY

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

How James Brown Invented Funk | Sound Field

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AihgZv1D5-4

How To Suck Carbon Dioxide Out of the Sky | Hot Mess

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tKtXojkwlK8

What’s the Real Cost of Owning A Pet? | Two Cents

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ma3Mt5BPlTE

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ? to Branden W., Edison Lewis, Vampire Wolf, Haithem Ghanem and Droidtigger who won our GIF CHALLENGE over at the Deep Look Community Tab, by identifying the special region in the canine skull which houses much of the smell ability: https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UC-3SbfTPJsL8fJAPK

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)

Bill Cass

Justin Bull

Daniel Weinstein

David Deshpande

Daisuke Goto

Karen Reynolds

Yidan Sun

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

KW

Shirley Washburn

Tanya Finch

johanna reis

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

Johnnyonnyful

Levi Cai

Jeanine Womble

Michael Mieczkowski

SueEllen McCann

TierZoo

James Tarraga

Willy Nursalim

Aurora Mitchell

Marjorie D Miller

Joao Ascensao

PM Daeley

Two Box Fish

Tatianna Bartlett

Monica Albe

Jason Buberel

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the Templeton Religion Trust, the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

With rows of Dr. Seuss-like flowers hidden deep inside, the corpse flower plays dead to lure some unusual pollinators.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

For a plant that emits an overpowering stench of rotting carcass, you’d think the corpse flower would have a PR problem.

But it’s quite the opposite: Anytime a corpse flower opens up at a botanical garden somewhere in the world visitors flock to catch a whiff and get a glimpse of the giant plant, which can grow up to 10 feet tall when it blooms and generally only does so every two to 10 years.

A corpse flower’s whole survival strategy is based on deception. It’s not a flower and it’s not a rotting dead animal, but it mimics both. Pollination remains out of sight, deep within the plant. KQED’s Deep Look staff was able to film inside a corpse flower, revealing the rarely-seen moment when the plant’s male flowers release glistening strings of pollen.

It’s not that the corpse flower is the only plant to attract pollinators like flies and beetles by putting out bad smells. Nor is it the only one that produces male and female flowers at the same time.

“The fact that it does all of this at this outsized scale – all of this together – is what’s so unique about it, biologically,” said Pati Vitt, senior scientist at the Chicago Botanic Garden.

When a titan arum is ready to flower, a stalk starts to grow out of the soil. Once it has reached four to 10 feet, a red “skirt” unfurls. Though it has the appearance of a petal, it’s really a modified leaf called a spathe that looks like a raw steak.

The yellow stalk underneath is called the spadix and it gives the plant its scientific name, Amorphophallus titanum, or roughly “giant deformed phallus.”

In its native Sumatra, the corpse flower opens for only 24 hours. In captivity, it often lasts longer. With just a day to reproduce, the stakes are high.

--- How many chemicals make up the smell of the corpse flower?

More than 30 chemicals make up the scent of the corpse flower, according to the 2017 paper “Studies on the floral anatomy and scent chemistry of titan arum” by researchers at the University of Mississippi, University of Florida, Gainsville, and Anadolu University in Turkey:

http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr..../botany/issues/bot-1

Some of the chemicals have a pleasant scent. But mostly, the corpse flower at first smells like funky cheese and rotting garlic, as a result of sulphur-smelling compounds. Hours later, the stink changes to what Vanessa Handley, at the University of California Botanical Garden at Berkeley describes as “dead rat in the walls of your house.”

---+ Read the entire article:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....018/01/23/this-giant

---+ For more information:

Great illustration on the lifecycle of the corpse flower by the Chicago Botanic Garden:

https://www.chicagobotanic.org/titan/faq

University of California Davis Botanical Conservatory:

http://greenhouse.ucdavis.edu/conservatory/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

This Mushroom Starts Killing You Before You Even Realize It

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bl9aCH2QaQY

A Real Alien Invasion Is Coming to a Palm Tree Near You

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S6a3Q5DzeBM

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

It’s Okay To Be Smart: How to Figure Out the Day of the Week For Any Date Ever

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=714LTMNJy5M

Above The Noise: Can Genetically Engineered Mosquitoes Help Fight Disease?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CB_h7aheAEM

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Bats have a brilliant way to find prey in the dark: echolocation. But to many of the moths they eat, that natural sonar is as loud as a jet engine. So some bats have hit on a sneakier, scrappier way to hunt.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Bats have been the only flying mammals for about 50 million years. Most species, with the exception of the fruit bats, use echolocation -- their built-in sonar -- to detect prey and snatch it from the air.

But not pallid bats. They hunt insects and arachnids that live on the ground by tracking their movements with another sense: hearing. In the final moments of their attack, they land and pluck their prey from the ground, a behavior called gleaning.

It took millions of years for bats to develop the lethal pairing of flight and echolocation. Why would a bat “go back” to a more primitive hunting style?

Many scientists believe the answer may have less to do with the bats alone than with moths, their principal food. In what these scientists describe as an “arms race” of evolution, many moth species have adapted to hear when they’re being tracked and to deploy counter-measures to bat echolocation.

These developments have driven some bats to seek alternate means of catching a meal – in part by keeping their sonar volume down. Pallid bats and other so-called “whispering bats” still use their echolocation to navigate. The volume navigational sonar is much quieter, more like a dishwasher.

For the pallid bat, part of occupying that niche has also meant evolving immunity scorpion venom. Another arms race.

--- Do all bats drink blood?

No, only three bat species are exclusive “hemovores” (blood-eaters), and only one of those, the common vampire bat, prefers mammals.

--- Why can’t humans hear echolocation?

Bat echolocation calls, whether for hunting or navigation – are too high-pitched for our ears to hear.

--- Do all bats carry rabies?

Only ½ to one percent of bats carry rabies. If a bat seems sick, rabies could be the cause. You should never touch any bat that you find.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/10/10/these-whis

---+ For more information:

Visit the Razak Lab at UC Riverside:

http://www.faculty.ucr.edu/~khaleel/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

A Real Alien Invasion Is Coming to a Palm Tree Near You

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S6a3Q5DzeBM

How Mosquitoes Use Six Needles to Suck Your Blood

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rD8SmacBUcU

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Origin Of Everything: The True Origin of Killer Clowns

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T5_Li2whOHA

Physics Girl: Fire in Freefall

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VAA_dNq_-8c

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

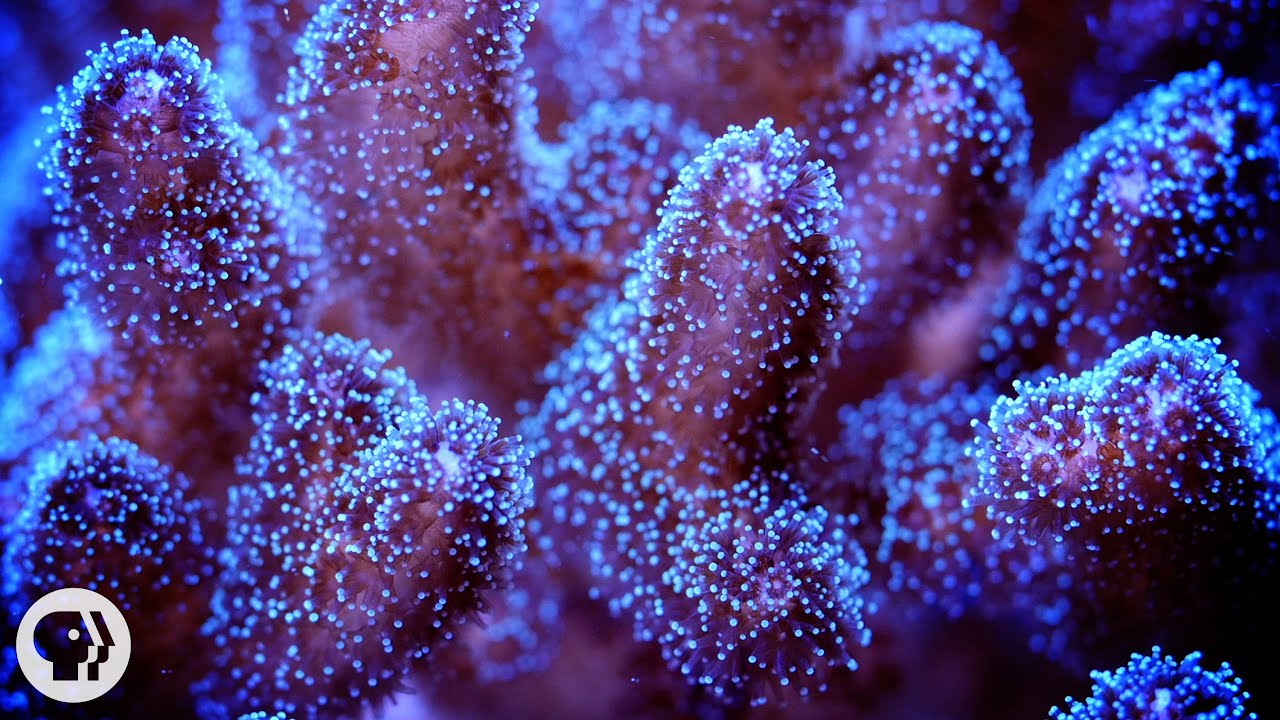

Some corals look like undersea gardens, gently blowing in the breeze. Others look like alien brains. But in their skeletons are clues that promise to give scientists a detailed picture of the weather from 500 years ago. Reading these bones? Easy. As long as you have the world's most powerful X-ray laser.

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Is coral a plant or animal?

Corals are unusual creatures. They are actually a partnership- or symbiosis- between an animal (a polyp) and a plant (algae) in which they work together to survive and thrive.

How does coral grow?

Tiny animals called polyps form an exoskeleton to live in. When one polyp dies, another builds a new home right on top of the old one. Beneath lies the abandoned exoskeletons, like an ancient city made of layer upon layer of old dwellings.

What is coral made of?

Coral exoskeletons are mostly made of calcium carbonate. But sometimes the polyps incorporate tiny amounts of other elements from the surrounding water, including the element strontium. Biologists don’t fully understand why polyps absorb strontium, but it’s a phenomenon that happens consistently across the world’s oceans.

When sea surface temperatures are warmer, corals absorb less strontium into their exoskeletons. When they are colder, they absorb more. By comparing the strontium-to-calcium ratio over time, scientists are able to reconstruct sea surface temperatures from the past. They also can chart long-term climate cycles that occurred over the lifespan of the coral. Since these corals can live for over 500 years, this gives us insights into the weather hundreds of years before written scientific records.

Read the article for this video on KQED Science:

http://ww2.kqed.org/science/20....15/07/07/what-happen

--

More great Deep Look episodes:

Where Are the Ants Carrying All Those Leaves?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-6oKJ5FGk24

What Happens When You Put a Hummingbird in a Wind Tunnel?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JyqY64ovjfY

Pygmy Seahorses: Masters of Camouflage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3CtGoqz3ww

See also another great video from the PBS Digital Studios!

It’s Okay to Be Smart: The Oldest Living Things In The World

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgspUYDwnzQ

More KQED Science:

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science: http://ww2.kqed.org/science

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

The archerfish hunts by spitting water at terrestrial targets with weapon-like precision, and can even tell human faces apart. Is this fish smarter than it looks?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Humans always have assumed we’ve cornered the market on intelligence. But because of archerfish and other bright lights in the animal kingdom, that idea is itself evolving.

Archerfish normally make their living in the mangrove forests of Southeast Asia and Australia, where they spit water at ants, beetles and other insects living on the trees’ half-submerged roots. The fish’s high-pressure projectiles knock prey from their perches into the water, and the fish swoops in.

This novel feeding behavior, restricted to only seven species of fish, has attracted the attention of researchers ever since it was first described in 1764.

The jet’s tip and tail unite at the moment of impact, which is critical to the success of the attack, especially as the target distance approaches the limit of the fish’s maximum spitting range of about six feet. The fish accomplishes this feat of timing through deliberate control of its highly-evolved mouthparts, in particular its lips, which act like an adjustable hose that can expand and contract while releasing the water.

So in a way, to hit a target that’s further away, the fish doesn’t spit harder. It spits smarter. But just how smart is an archerfish?

Using the archerfish’s spitting habits as a starting point, one researcher trained some lab fish to spit at an image of one human face with food rewards. Then, on a monitor suspended over the fish tank, she showed them a series of other faces, in pairs, adding in the familiar one.

When the trained fish saw that familiar face, they would spit, to a high degree of accuracy. In a sense, the fish “recognized” the face, which should have been beyond the capacity of its primitive brain.

--- Where do archerfish live?

In Thailand, Australia, and other parts of Southeast Asia, usually in mangrove forests.

--- What do archerfish eat?

Insects and spiders that live close to the waterline. Archerfish won’t eat anything once it’s sinks too far below the surface.

--- How do archerfish spit?

They squeeze water through their mouth opening, using specially evolved mouthparts.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/01/31/archerfish

---+ For more information:

Visit the California Academy of Sciences: http://www.calacademy.org/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Sea Urchins Pull Themselves Inside Out to be Reborn

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ak2xqH5h0YY

Sticky. Stretchy. Waterproof. The Amazing Underwater Tape of the Caddisfly

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z3BHrzDHoYo

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Gross Science: Sea Cucumbers Have Multipurpose Butts

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjnvRKDdaWY

Physics Girl: DIY Lightning Experiment! Make a SHOCKING Capacitor

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rG7N_Zv6_gQ

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

To protect herself and her eggs, female webspinners shoot super-fine silk from their front feet. They weave the strands to build a shelter that serves as a tent, umbrella and invisibility cloak. But shooting silk from her feet requires her to moonwalk to get around.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Please support us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

---

With the holidays just around the corner, it’s that time of year when you’re ready to burn off Thanksgiving turkey and Christmas cookie calories by heading outdoors for a hike. Maybe you’ve noticed what looks like spider webs woven in between weeds alongside the trail, or poking out from under rocks or draped across logs.

But take a closer look – those webs might actually not be spider webs. A lot of them are silken habitats, known as 'galleries,' created by insects called webspinners.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1949380/

--- Where do webspinners live?

You find them living in a variety of habitats all over the world, from humid tropical rain forests to dry, hotter areas.

--- Do only adults spin silk?

Actually, everybody spins silk, the males, females and the nymphs. It’s completely unique for insects to have that ability.

--- Who is briefly featured in the episode turning over the log?

While only her hands make a short cameo in the video, Janice Edgerly-Rooks, is a professor of biology at Santa Clara University. She’s been studying these insects for most of her career and was invaluable to us in the production of our episode.

---+ For more information:

Janice Edgerly-Rooks’ at Santa Clara University

https://www.scu.edu/cas/biolog....y/faculty/edgerly-ro

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

It’s a Bug’s Life: https://www.youtube.com/playli....st?list=PLdKlciEDdCQ

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to the following fans on our YouTube community tab for correctly identifying the insects *besides webspinners* that produce silk with their front feet: the balloon flies of the Empididae family, such as Hilara maura.

João Farminhão

TheWhiteScatterbug

Ryan Stuart

Anthony Nguyen

henry chu

biozcw

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Alice Kwok

Allen

Amber Miller

Aurora

Aurora Mitchell

Bethany

Bill Cass

Blanca Vides

Burt Humburg

Caitlin McDonough

Cameron

Carlos Carrasco

Chris B Emrick

Chris Murphy

Cindy McGill

Companion Cube

Cory

Daisuke Goto

Daniel Weinstein

David Deshpande

David Esperanza

Dean Skoglund

Edwin Rivas

Egg-Roll

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

Geidi Rodriguez

Gerardo Alfaro

Guillaume Morin

Ivan Alexander

Jacob Stone

Jane Orbuch

JanetFromAnotherPlanet

Jeanne Sommer

Joao Ascensao

johanna reis

Johnnyonnyful

Joshua Murallon Robertson

Justin Bull

Kallie Moore

Karen Reynolds

Katherine Schick

Kathleen R Jaroma

Kendall Rasmussen

Kristy Freeman

KW

Kyle Fisher

Laura Sanborn

Laurel Przybylski

Leonhardt Wille

Levi Cai

Louis O'Neill

lunafaaye

Mary Truland

monoirre

Natalie Banach

Nathan Wright

Nicolette Ray

Nikita

Noreen Herrington

Nousernamepls

Osbaldo Olvera

Pamela Parker

PM Daeley

raspberry144mb

riceeater

Richard Shalumov

Rick Wong

Robert Amling

Robert Warner

Roberta K Wright

Sarah Khalida Mohamad

Sayantan Dasgupta

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

Shirley Washburn

Silvan Wendland

Simone Galavazi

Sonia Tanlimco

Stefficael Uebelhart

SueEllen McCann

Supernovabetty

Syniurge

Tea Torvinen

TierZoo

Titania Juang

Trae Wright

Two Box Fish

WhatzGames

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

#webspinners #insect #deeplook

There's a chemical arms race going on in the Sonoran Desert between a highly venomous scorpion and a particularly ferocious mouse. The outcome of their battle may one day change the way doctors treat pain in people.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Commonly found in the Sonoran Desert, the Arizona bark scorpion (Centruroides sculpturatus) is the most dangerous scorpion in the continental United States. According to Keith Boesen, Director of the Arizona Poison & Drug Information Center, about 15,000 Americans report being stung by scorpions every year in the U.S. The worst stings, about 200 annually, are attributed to this one species. Its sting can cause sharp pain along with tingling, swelling, numbness, dizziness, shortness of breath, muscular convulsions, involuntary eye movements, coughing and vomiting. Children under two years old are especially vulnerable. Since 2000, three human deaths have been attributed to the Arizona bark scorpion in the United States, all within Arizona.

But there is one unlikely creature that appears unimpressed. While it may not look the part, the Southern grasshopper mouse (Onychomys torridus) is an extremely capable hunter. It fearlessly stalks and devours any beetles or grasshoppers that have the misfortune to cross its path. But this mouse has a particular taste for scorpions.

The scorpion venom contains neurotoxins that target sodium and potassium ion channels, proteins embedded within the surface of the nerve and muscle cells that play an important role in regulating the sensation of pain. Activating these channels sends signals down the nerves to the brain. That’s what causes the excruciating pain that human victims have described as the feeling like getting jabbed with a hot needle. Others compare the pain to an electric shock. But the grasshopper mouse has an entirely different reaction when stung.

Within the mouse, a special protein in one of the sodium ion channels binds to the scorpion’s neurotoxin. Once bound, the neurotoxin is unable to activate the sodium ion channel and send the pain signal. Instead it has the entirely opposite effect. It shuts down the channel, keeping it from sending any signals, which has a numbing effect for the mouse.

--- How many species of scorpion are there?

There are almost 2,000 scorpion species, but only 30 or 40 have strong enough poison to kill a person.

--- Are scorpions insects?

Scorpions are members of the class Arachnida and are closely related to spiders, mites, and ticks.

--- Where do Arizona bark scorpions live?

Commonly found in the Sonoran Desert, the Arizona bark scorpion (Centruroides sculpturatus) is the most dangerous scorpion in the continental United States. The Arizona bark scorpion’s preference for hanging to the underside of objects makes dangerous encounters with humans more likely.

Read the entire article on KQED Science:

http://ww2.kqed.org/science/20....16/03/08/stinging-sc

For more information:

Michigan State University Venom Evolution: http://venomevolution.zoology.msu.edu/

Institute for Biodiversity Science and Sustainability at the California Academy of Sciences: http://www.calacademy.org/scientists

More great Deep Look episodes:

What Happens When You Zap Coral With The World's Most Powerful X-ray Laser?

https://youtu.be/aXmCU6IYnsA

These 'Resurrection Plants' Spring Back to Life in Seconds

https://youtu.be/eoFGKlZMo2g

See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay to Be Smart: Your Salad Is Trying To Kill You

https://youtu.be/8Ofgj2KDbfk

It's Okay to Be Smart: The Oldest Living Things In The World

https://youtu.be/jgspUYDwnzQ

For more content from KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Most flowering plants are more than willing to spread their pollen around. But some flowers hold out for just the right partner. Bumblebees and other buzz pollinators know just how to handle these stubborn flowers. They vibrate the blooms, shaking them until they give up the nutritious pollen.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

In the summertime, the air is thick with the low humming of bees delivering pollen from one flower to the next. If you listen closely, a louder buzz may catch your ear.

This sound is the key to a secret stash of pollen that some flowers hide deep within their anthers, the male parts of the plant. Only pollinators that buzz in just the right way can vibrate tiny grains out of minuscule holes at the top of the anthers for a protein-rich snack.

The strategy, called buzz-pollination, is risky. But it’s also critical to human agriculture. Tomatoes, potatoes and eggplants need wild populations of buzz pollinators, such as bumblebees, to produce fruit. Honeybees can’t do it.

Plants need a way to get the pollen — basically sperm — to the female parts of another flower. Most plants lure animal pollinators to spread these male gametes by producing sugary nectar. The bee laps up the sweet reward, is dusted with pollen and passively delivers it to the next bloom.

In contrast, buzz-pollinated flowers encourage bees to eat the pollen directly and hope some grains will make it to another flower. The evolutionary strategy is baffling to scientists.

“The flower is almost like playing hard to get,” says Anne Leonard, a biologist at the University of Nevada, Reno who studies buzz pollination. “It’s intriguing because these buzz-pollinated plants ask for a huge energy investment from the bees, but don’t give much back.”

--- What is buzz pollination?

Most flowering plants use sugary nectar as bait to attract bees and other pollinators, which get coated in pollen along the way. And since bees are messy, they inadvertently scatter some of that pollen onto the female part of the next flower they visit.

But some flowers lock their pollen up in their anthers, the male parts of the flower, instead of giving it away freely. The only way for the pollen to escape is through small holes called pores. Some pollinators like bumblebees (but not honeybees) are able to vibrate the flower’s anthers which shakes up the pollen and causes it to spew out of the pores.

The bumblebee collects the pollen and uses it as a reliable and protected source of protein.

--- What important crops use buzz pollination to make food?

The most important crops that use buzz pollination are potatoes, tomatoes, pumpkins, eggplants, cranberries and blueberries

--- What animals are capable of buzz pollination?

Many types of bees engage in buzz pollination, also called sonication. The most common is probably the bumblebee. Honeybees generally don’t use buzz pollination.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....016/07/19/this-vibra

---+ For more information:

Anne Leonard Lab, University of Nevada, Reno | Department of Biology

http://www.anneleonard.com/buzz-pollination/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

These Lizards Have Been Playing Rock-Paper-Scissors for 15 Million Years | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rafdHxBwIbQ

Winter is Coming For These Argentine Ant Invaders | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=boyzWeHdtiI

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay to Be Smart: Why Don't Other Animals Wear Glasses?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LhubEq6W9GE

Gross Science: The World's Most Expensive Fungus

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iV4WHFU2Id8

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

You may think that you've got the house to yourself, but chances are you have about 100 different types of animals living with you. Many of them are harmless, but a few can be dangerous in ways you wouldn't expect. New research explores exactly whom you share your home with and how they got there.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

---+ About Dust Mites

With the warming weather it’s the season for spring cleaning. But before you reach for the broom and mop, take a moment to look at who else is sharing your home with you. The number of uninvited guests you find in your dustpan may surprise you.

A recent study published in the journal PeerJ took up the challenge of cataloging the large numbers of tiny animals that live in human dwellings. The researchers found that the average home contains roughly 100 different species of arthropods, including familiar types like flies, spiders and ants, but also some kinds that are less well known like gall wasps and book lice. And no matter how much human residents may clean, there will always be a considerable number of mini-roommates.

“Even as entomologists we were really surprised. We live in our houses all the time, so we thought we’d be more familiar with the kind of things we’d come across. There was a surprising level of biodiversity,” said Michelle Trautwein, assistant curator of entomology at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco.

---+ What are dust mites?

Dust mites are tiny animals, related to spiders, that are usually too small to be seen with the naked eye. They feed on dead skin that humans shed every day and their droppings may cause allergic reactions and may aggravate asthma, especially in children.

---+ How do you minimize dust mites?

It’s practically impossible to completely rid a home of dust mites, but frequent cleaning and removing carpeting can help. Wet cleaning like mopping helps keep from stirring up dust while cleaning. The most effective way to keep dust mite populations down is to keep the indoor humidity level low. Dust mites can only survive in humid environments.

---+ How do you see dust mites?

Dust mites are about .2mm long. You can see dust mites with a powerful magnifying glass, but you can get a better view by using a microscope.

Read the entire article on KQED Science:

http://ww2.kqed.org/science/20....16/04/05/meet-the-du

---+ More great DEEP LOOK episodes:

The Bombardier Beetle And Its Crazy Chemical Cannon

http://ww2.kqed.org/science/20....16/04/05/meet-the-du

Where Are the Ants Carrying All Those Leaves?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-6oKJ5FGk24

Banana Slugs: Secret of the Slime

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mHvCQSGanJg

--- Super videos from the PBS Digital Studios Network!

It's Okay To Be Smart: How Do Bees Make Honey?

https://youtu.be/nZlEjDLJCmg

Gross Science: What's Living On Your Contact Lenses?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wRMKzsU9zec

Gross Science: You Have Mites Living On Your Face

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oMmCWx8vySs

--- More content from KQED Science, Northern California's PBS and NPR affiliate:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

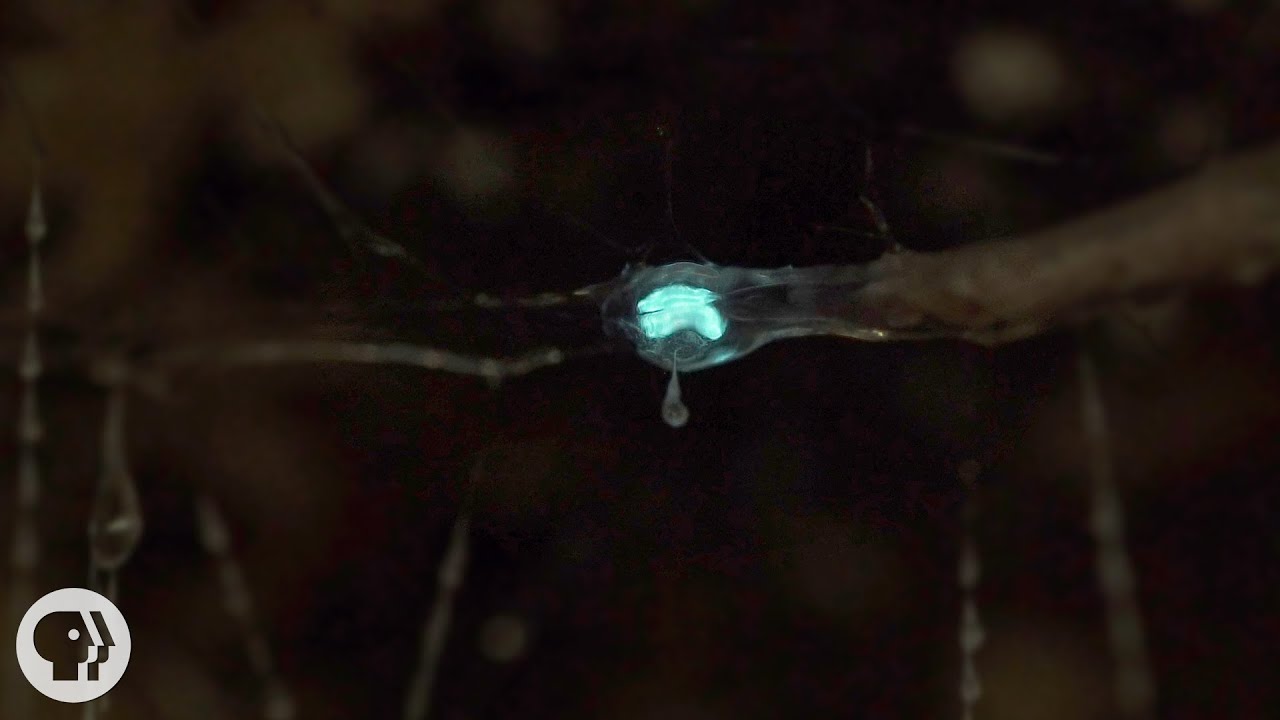

The glow worm colonies of New Zealand's Waitomo Caves imitate stars to confuse flying insects, then trap them in sticky snares and eat them alive.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is science up close - really, really close. An ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Like fireflies, the spectacular worms of New Zealand’s Waitomo Caves glow by breaking down a light-emitting protein. But unlike the yellow mating flashes of fireflies, the glow worms’ steady blue light has a more insidious purpose: it’s bait.

The strategy is simple. Many of the glow worms’ prey are insects, including moths, that navigate by starlight. With imposter stars all around, the insects become disoriented and fly into a waiting snare. Once the victim has exhausted itself trying to get free, the glow worm reels in the catch.

The prey is typically still alive when it arrives at the glow worm’s mouth, which has teeth sharp enough to bore through insect exoskeletons.

Glow worms live in colonies, and researchers have noticed that individual worms seem to sync their lights to the members of their colony, brightening and dimming on a 24-hour cycle. There can be several colonies of glow worms in a cave, and studies have shown that different colonies are on different cycles, taking turns at peak illumination, when they’re most attractive to prey.

Not surprisingly, the worms glow brighter when they’re hungry.

--- How do glow worms glow?

Their light is the result of a chemical reaction. The worms break down a protein called luciferin using an enzyme, luciferase, in a specialized section of their digestive tract. The glow shines through their translucent skin.

--- Why do glow worms live in caves?

The glow worms need to be in a dark environment where their light can be seen. Caves also shelter them from the wind, which can tangle their dangling snares.

--- Where can I see glow worms?

The Waitomo Caves are on New Zealand’s North Island. Other New Zealand glow worm sites include the Te Anau caves, Lake Rotoiti, Paparoa National Park, and Waipu. A related species inhabits similar caves in eastern Australia.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....016/06/28/these-carn

---+ For more information:

Discover Waitomo: http://www.waitomo.com/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Winter is Coming For These Argentine Ant Invaders

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=boyzWeHdtiI

The Bombardier Beetle And Its Crazy Chemical Cannon

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BWwgLS5tK80

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay to Be Smart: Are You Smarter Than A Slime Mold?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K8HEDqoTPgk

Gross Science: Hookworms and the Myth of the "Lazy Southerner"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7BwgpYexMjk

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Check out America From Scratch: https://youtu.be/LVuEJ15J19s

A rattlesnake's rattle isn't like a maraca, with little bits shaking around inside. So how exactly does it make that sound?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Please support us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Watch America From Scratch: https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UClSZ6wHgU2h1W7eAG

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Rattlesnakes are ambush predators, relying on staying hidden to get close to their prey. They don’t sport the bright colors that some venomous snakes use as a warning to predators.

Fortunately, rattlesnakes have an unmistakable warning, a loud buzz made to startle any aggressor and hopefully avoid having to bite.

If you hear the rattlesnake’s rattle here’s what to do: First, stop moving! You want to figure out which direction the sound is coming from. Once you do, slowly back away.

If you do get bitten, immobilize the area and don't overly exert yourself. Immediately seek medical attention. You may need to be treated with antivenom.

DO NOT try to suck the venom out using your mouth or a suction device.

DO NOT try to capture the snake and stay clear of dead rattlesnakes, especially the head.

--- How do rattlesnakes make that buzzing sound?

The rattlesnake’s rattle is made up of loosely interlocking segments made of keratin, the same strong fibrous protein in your fingernails. Each segment is held in place by the one in front and behind it, but the individual segments can move a bit. When the snake shakes its tail, it sends undulating waves down the length of the rattle, and they click against each other. It happens so fast that all you hear is a buzz and all you see is a blur.

--- Why do rattlesnakes flick their tongue?

Like other snakes, rattlesnakes flick their tongues to gather odor particles suspended in liquid. The snake brings those scent molecules back to a special organ in the roof of their mouth called the vomeronasal organ or Jacobson's organ. The organ detects pheromones originating from prey and other snakes.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....945648/5-things-you-

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Stinging Scorpion vs. Pain-Defying Mouse | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w-K_YtWqMro&t=35s

---+ ?Congratulations ?to the following fans for coming up with the *best* new names for the Jacobson's organ in our community tab challenge:

Pigeon Fowl - "Noodle snoofer"

alex jackson - "Ye Ol' Factory"

Aberrant Artist - "Tiny boi sniffer whiffer"

vandent nguyen - "Smeller Dweller" and "Flicker Snicker"

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Allen, Aurora Mitchell, Beckie, Ben Espey, Bill Cass, Bluapex, Breanna Tarnawsky, Carl, Chris B Emrick, Chris Murphy, Cindy McGill, Companion Cube, Cory, Daisuke Goto, Daisy Trevino , Daniel Voisine, Daniel Weinstein, David Deshpande, Dean Skoglund, Edwin Rivas, Elizabeth Ann Ditz, Eric Carter, Geidi Rodriguez, Gerardo Alfaro, Ivan Alexander, Jane Orbuch, JanetFromAnotherPlanet, Jason Buberel, Jeanine Womble, Jeanne Sommer, Jiayang Li, Joao Ascensao, johanna reis, Johnnyonnyful, Joshua Murallon Robertson, Justin Bull, Kallie Moore, Karen Reynolds, Katherine Schick, Kendall Rasmussen, Kenia Villegas, Kristell Esquivel, KW, Kyle Fisher, Laurel Przybylski, Levi Cai, Mark Joshua Bernardo, Michael Mieczkowski, Michele Wong, Nathan Padilla, Nathan Wright, Nicolette Ray, Pamela Parker, PM Daeley, Ricardo Martinez, riceeater, Richard Shalumov, Rick Wong, Robert Amling, Robert Warner, Samuel Bean, Sayantan Dasgupta, Sean Tucker, Shelley Pearson Cranshaw, Shirley Washburn, Sonia Tanlimco, SueEllen McCann, Supernovabetty, Tea Torvinen, TierZoo, Titania Juang, Two Box Fish, WhatzGames, Willy Nursalim, Yvan Mostaza,

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

When attacked, this beetle sets off a rapid chemical reaction inside its body, sending predators scrambling. This amazing chemical defense has some people scratching their heads: How could such a complex system evolve gradually—without killing the beetle too?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

The bombardier beetle, named for soldiers who once operated artillery cannons, has a surprising secret to use against potential predators.

When attacked, the beetle mixes a cocktail of compounds inside its body that produces a fast-moving chemical reaction. The reaction heats the mix to the boiling point, then propels it through a narrow abdominal opening with powerful force. By turning the end of its abdomen on an assailant, the beetle can even aim the spray.

The formidable liquid, composed of three main ingredients, both burns and stings the attacker. It can kill a small adversary, such as an ant, and send larger foes, like spiders, frogs, and birds, fleeing in confusion.

How do bombardier beetles defend themselves?

They manufacture and combine three reactive substances inside their bodies. The chemical reaction is exothermic, meaning it heats the combination to the boiling point, producing a hot, stinging spray, which the beetle can point at an enemy.

What does a bombardier beetle spray?

It’s a combination of hydroquinone and hydrogen peroxide (like what you can buy in the store). The reaction between these two is catalyzed by an enzyme, produced by glands in the beetle, which is the spark that makes the reaction so explosive.

Why is it called a bombardier beetle?

“Bombardier” is an old French word for a solider who operates artillery.

Read the entire article on KQED Science:

http://ww2.kqed.org/science/20....16/03/22/kaboom-this

--- More great DEEP LOOK episodes:

Halloween Special: Watch Flesh-Eating Beetles Strip Bodies to the Bone

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Np0hJGKrIWg

What Happens When You Put a Hummingbird in a Wind Tunnel?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JyqY64ovjfY

Nature's Scuba Divers: How Beetles Breathe Underwater

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T-RtG5Z-9jQ

--- Super videos from the PBS Digital Studios Network!

Nature's Most Amazing Animal Superpowers | It's Okay to Be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e69yaWDkVGs

Why Don’t These Cicadas Have Butts? | Gross Science

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IDBkj3DjNSM

--- For more content from your local PBS and NPR affiliate:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Support Deep Look on Patreon!!

https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Why can't you just flick a tick? Because it attaches to you with a mouth covered in hooks, while it fattens up on your blood. For days. But don't worry – there *is* a way to pull it out.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Spring is here. Unfortunately for hikers and picnickers out enjoying the weather, the new season is prime time for ticks, which can transmit bacteria that cause Lyme disease.

How they latch on – and stay on – is a feat of engineering that scientists have been piecing together. Once you know how a tick’s mouth works, you understand why it’s impossible to simply flick a tick.

The key to their success is a menacing mouth covered in hooks that they use to get under the surface of our skin and attach themselves for several days while they fatten up on our blood.

“Ticks have a lovely, evolved mouth part for doing exactly what they need to do, which is extended feeding,” said Kerry Padgett, supervising public health biologist at the California Department of Public Health in Richmond. “They're not like a mosquito that can just put their mouth parts in and out nicely, like a hypodermic needle.”

Instead, a tick digs in using two sets of hooks. Each set looks like a hand with three hooked fingers. The hooks dig in and wriggle into the skin. Then these “hands” bend in unison to perform approximately half-a-dozen breaststrokes that pull skin out of the way so the tick can push in a long stubby part called the hypostome.

“It’s almost like swimming into the skin,” said Dania Richter, a biologist at the Technische Universität Braunschweig in Germany, who has studied the mechanism closely. “By bending the hooks it’s engaging the skin. It’s pulling the skin when it retracts.”

The bottom of their long hypostome is also covered in rows of hooks that give it the look of a chainsaw. Those hooks act like mini-harpoons, anchoring the tick to us for the long haul.

“They’re teeth that are backwards facing, similar to one of those gates you would drive over but you're not allowed to back up or else you'd puncture your tires,” said Padgett.

--- How to remove a tick.

Kerry Padgett, at the California Department of Public Health, recommends grabbing the tick close to the skin using a pair of fine tweezers and simply pulling straight up.

“No twisting or jerking,” she said. “Use a smooth motion pulling up.”

Padgett warned against using other strategies.

“Don't use Vaseline or try to burn the tick or use a cotton swab soaked in soft soap or any of these other techniques that might take a little longer or might not work at all,” she said. “You really want to remove the tick as soon as possible.”

--- What happens if the mouth of a tick breaks off in your skin?

Don’t worry if the tick’s mouth parts stay behind when you pull.

“The mouth parts are not going to transmit disease to people,” said Padgett.

If the mouth stayed behind in your skin, it will eventually work its way out, sort of like a splinter does, she said. Clean the bite area with soap and water and apply antibiotic ointment.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science: https://www.kqed.org/science/1....920972/how-ticks-dig

---+ For more information:

Centers for Disease Control information on Lyme disease:

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/

Mosquito & Vector Control District for San Mateo County, California:

https://www.smcmvcd.org/ticks

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

How Mosquitoes Use Six Needles to Suck Your Blood

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rD8SmacBUcU

So … Sometimes Fireflies Eat Other Fireflies

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oWdCMFvgFbo

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Above the Noise: Are Energy Drinks Really that Bad?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5l0cjsZS-eM

It’s Okay To Be Smart: Inside an ICE CAVE! - Nature's Most Beautiful Blue

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P7LKm9jtm8I

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #ticks #tickbite

Termites cause billions of dollars in damage annually – but they need help to do it. So they carry tiny organisms around with them in their gut. Together, termites and microorganisms can turn the wood in your house into a palace of poop.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Termites such as dampwood termites use their cardboard-like poop pellets to build up their nests, turning a human house into a termite toilet. “They build their own houses out of their own feces,” said entomologist Michael Scharf, of Purdue University, in Indiana.

And while they’re using their poop as a building material, termites are also feeding on the wood. They’re one of the few animals that can extract nutrients from wood. But it turns out that they need help to do this.