Animales y Mascotas

Why are itchy lice so tough to get rid of and how do they spread like wildfire? They have huge claws that hook on hair perfectly, as they crawl quickly from head to head.

JOIN our Deep Look community on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is an ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Head lice can only move by crawling on hair. They glue their eggs to individual strands, nice and close to the scalp, where the heat helps them hatch. They feed on blood several times a day. And even though head lice can spread by laying their eggs in sports helmets and baseball caps, the main way they get around is by simply crawling from one head to another using scythe-shaped claws.

These claws, which are big relative to a louse’s body, work in unison with a small spiky thumb-like part called a spine. With the claw and spine at the end of each of its six legs, a louse grasps a hair strand to hold on, or quickly crawl from hair to hair like a speedy acrobat.

Their drive to stay on a human head is strong because once they’re off and lose access to their blood meals, they starve and die within 15 to 24 hours.

--- How do you kill lice?

Researchers found in 2016 that lice in the U.S. have become resistant to over-the-counter insecticide shampoos, which contain natural insecticides called pyrethrins, and their synthetic version, known as pyrethroids.

Other products do still work against lice, though. Prescription treatments that contain the insecticides ivermectin and spinosad are effective, said entomologist John Clark, of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. They’re prescribed to kill both lice and their eggs. Clark said treatments such as suffocants, which block the lice’s breathing holes, and hot-air devices that dry them up, also work. He added that tea tree oil works both as a repellent and a “pretty good” insecticide. Combing lice and eggs out with a special metal comb is also a recommended treatment.

--- How long do lice survive?

It takes six to nine days for their eggs to hatch and about as long for the young lice to grow up and start laying their own eggs. Adult lice can live on a person’s head for up to 30 days, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

--- Can your pet give you lice?

No. Human head lice only live on our heads. They can’t really move to other parts of our body or onto pets.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....939435/how-lice-turn

---+ For more information:

Visit the CDC’s page on head lice: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/head/index.html

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

How Mosquitoes Use Six Needles to Suck Your Blood:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rD8SmacBUcU

How Ticks Dig In With a Mouth Full of Hooks:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_IoOJu2_FKE

---+ Shoutout!

Congratulations to ?HaileyBubs, Tiffany Haner, cjovani78z, יואבי אייל, and Bellybutton King?, who were the first to correctly ID the species and subspecies of insect in this episode over at the Deep Look Community Tab:

https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UC-3SbfTPJsL8fJAPK

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Bill Cass, Justin Bull, Daniel Weinstein, David Deshpande, Daisuke Goto, Karen Reynolds, Yidan Sun, Elizabeth Ann Ditz, KW, Shirley Washburn, Tanya Finch, johanna reis, Shelley Pearson Cranshaw, Johnnyonnyful, Levi Cai, Jeanine Womble, Michael Mieczkowski, TierZoo, James Tarraga, Willy Nursalim, Aurora Mitchell, Marjorie D Miller, Joao Ascensao, PM Daeley, Two Box Fish, Tatianna Bartlett, Monica Albe, Jason Buberel

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the Templeton Religion Trust, the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

We've all heard that each and every snowflake is unique. But in a lab in sunny southern California, a physicist has learned to control the way snowflakes grow. Can he really make twins?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

California's historic drought is finally over thanks largely to a relentless parade of powerful storms that have brought the Sierra Nevada snowpack to the highest level in six years, and guaranteed skiing into June. All that snow spurs an age-old question -- is every snowflake really unique?

“It’s one of these questions that’s been around forever,” said Ken Libbrecht, a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “I think we all learn it in elementary school, the old saying that no two snowflakes are alike.”

--- How do snowflakes form?

Snow crystals form when humid air is cooled to the point that molecules of water vapor start sticking to each other. In the clouds, crystals usually start forming around a tiny microscopic dust particle, but if the water vapor gets cooled quickly enough the crystals can form spontaneously out of water molecules alone. Over time, more water molecules stick to the crystal until it gets heavy enough to fall.

--- Why do snowflakes have six arms?

Each water molecule is each made out of one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms. As vapor, the water molecules bounce around slamming into each other. As the vapor cools, the hydrogen atom of one molecule forms a bond with the oxygen of another water molecule. This is called a hydrogen bond. These bonds make the water molecules stick together in the shape of a hexagonal ring. As the crystal grows, more molecules join fitting within that same repeating pattern called a crystal array. The crystal keeps the hexagonal symmetry as it grows.

--- Is every snowflake unique?

Snowflakes develop into different shapes depending on the humidity and temperature conditions they experience at different times during their growth. In nature, snowflakes don’t travel together. Instead, each takes it’s own path through the clouds experiencing different conditions at different times. Since each crystal takes a different path, they each turn out slightly differently. Growing snow crystals in laboratory is a whole other story.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/04/11/identical-

---+ For more information:

Ken Libbrecht’s online guide to snowflakes, snow crystals and other ice phenomena.

http://snowcrystals.com/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Can A Thousand Tiny Swarming Robots Outsmart Nature? | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dDsmbwOrHJs

What Gives the Morpho Butterfly Its Magnificent Blue? | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=29Ts7CsJDpg&list=PLdKlciEDdCQDxBs0SZgTMqhszst1jqZhp&index=48

The Amazing Life of Sand | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VkrQ9QuKprE&list=PLdKlciEDdCQDxBs0SZgTMqhszst1jqZhp&index=51

The Hidden Perils of Permafrost | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wxABO84gol8

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

The Science of Snowflakes | It’s OK to be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fUot7XSX8uA

An Infinite Number of Words for Snow | PBS Idea Channel

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CX6i2M4AoZw

Is an Ice Age Coming? | Space Time | PBS Digital Studios

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ztninkgZ0ws

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Take the PBSDS survey: https://to.pbs.org/2018YTSurvey

Explore our VR slug and support us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

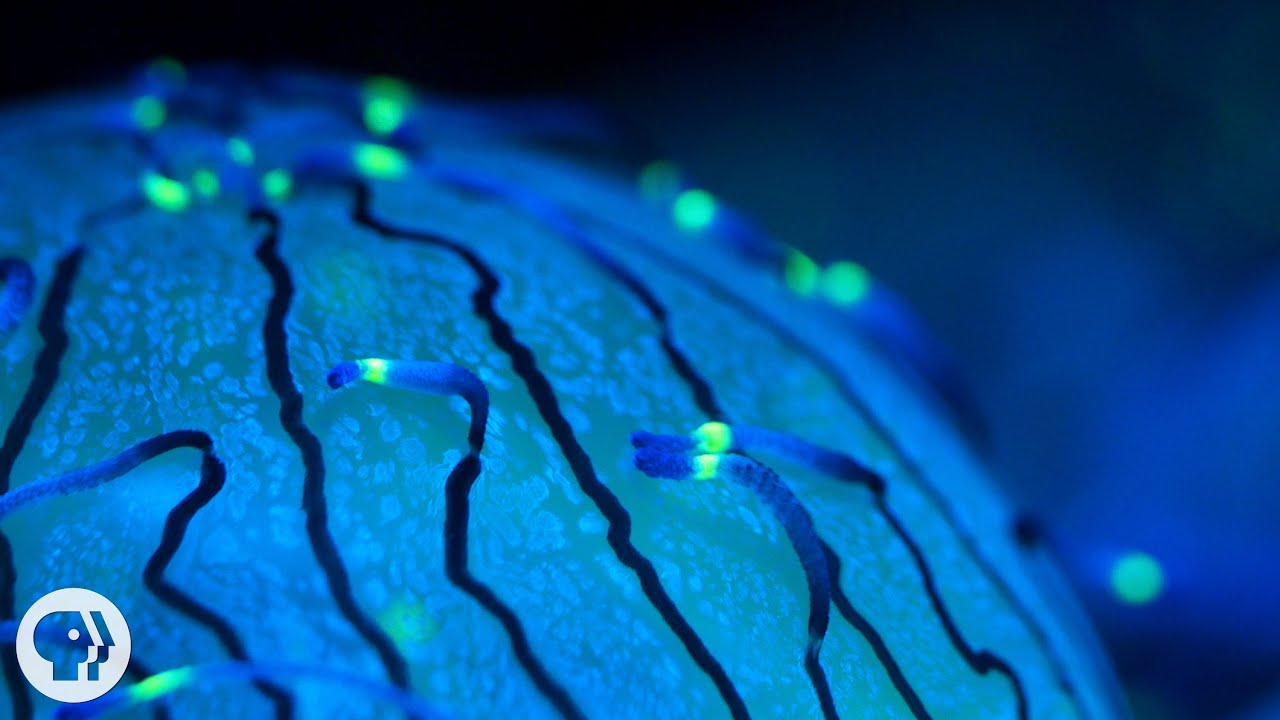

Nudibranchs may look cute, squishy and defenseless ... but watch out. These brightly-colored sea slugs aren't above stealing weapons from their prey.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

The summer months bring low morning tides along the California coast, providing an opportunity to see one of the state’s most unusual inhabitants, sea slugs.

Also called nudibranchs, many of these relatives of snails are brightly colored and stand out among the seaweed and anemones living next to them in tidepools.

“Some of them are bright red, blue, yellow -- you name it,” said Terry Gosliner, senior curator of invertebrate zoology and geology at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. “They're kind of designer slugs.”

But without a protective shell, big jaws or sharp claws, how do these squishy little creatures get away with such flamboyant colors in a habitat full of predators?

As it turns out, the nudibranchs’ colors serve as a warning to predators: These sea slugs are packing some very sophisticated defenses. And some aren’t above stealing weapons from their prey.

Gosliner and Brenna Green and Emily Otstott, graduate students at San Francisco State University, were out at dawn earlier this summer searching tidepools and floating docks around the Bay Area. They want to learn more about how these delicate little sea slugs survive and how changing ocean temperatures might threaten their futures.

Nudibranchs come in a staggering variety of shapes and sizes. Many accumulate toxic or bad-tasting chemicals from their prey, causing predators like fish and crabs to learn that the flashy colors mean the nudibranch wouldn’t make a good meal.

--- What are nudibranchs?

Nudibranchs are snails that lost their shell over evolutionary time. Since they don’t have a shell for protection, they have to use other ways to defend themselves like accumulating toxic chemicals in their flesh to make them taste bad to predators. Some species of nudibranchs eat relatives of jellyfish and accumulate the stingers within their bodies for defense.

--- Why do nudibranchs have such bright colors?

The bright colors serve as a signal to the nudibranch’s predators that they are not good to eat. If a fish or crab bites a nudibranch, it learns to associate the bad taste with the bright colors which tends to make them reluctant to bite a nudibranch with those colors in the future.

--- What does nudibranch mean?

The word nudibranch comes from Latin. It means naked gills. They got that name because some species of nudibranchs have an exposed ring of gills on their back that they use to breath.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....929993/this-adorable

---+ For more information:

Learn more about Terry Gosliner’s work with nudibranchs

https://www.calacademy.org/sta....ff/ibss/invertebrate

Learn more about Chris Lowe’s work with plankton

http://lowe.stanford.edu/

Learn more about Jessica Goodheart’s study of nematocyst sequestration

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.co....m/doi/full/10.1111/i

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

From Drifter to Dynamo: The Story of Plankton | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/jUvJ5ANH86I

For Pacific Mole Crabs It's Dig or Die | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/tfoYD8pAsMw

The Amazing Life of Sand | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/VkrQ9QuKprE

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

Why Are Hurricanes Getting Stronger? | Hot Mess

https://youtu.be/2E1Nt7JQRzc

When Fish Wore Armor | Eons

https://youtu.be/5pVTZH1LyTw

Why Do We Wash Our Hands After Going to the Bathroom? | Origin of Everything

https://youtu.be/fKlpGs34-_g

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the Templeton Religion Trust and the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #nudibranch #seaslug

Kidnapper ants raid other ant species' colonies, abduct their young and take them back to their nest. When the enslaved babies grow up, the kidnappers trick them into serving their captors – hunting, cleaning the nest, even chewing up their food for them.

Please join our community on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

A miniature drama is playing out on the forest floor in California’s preeminent mountain range, the Sierra Nevada, at this time of year. As the sun sets, look closely and you might see a stream of red ants frantically climbing over leaves and rocks.

They aren’t looking for food. They’re looking for other ants. They’re kidnappers.

“It’s hard to know who you're rooting for in this situation,” says Kelsey Scheckel, a graduate student at UC Berkeley who studies kidnapper ants. “You're just excited to be a bystander.”

On this late summer afternoon, Scheckel stares intently over the landscape at the Sagehen Creek Field Station, part of the University of California’s Natural Reserve System, near Truckee, California.“The first thing we do is try to find a colony with two very different-looking species cohabitating,” Scheckel says.

“That type of coexistence is pretty rare. As soon as we find that, we can get excited.”

--- How do ants communicate?

Ants mostly use their sense of smell to learn about the world around themselves and to recognize nestmates from intruders. They don’t have noses. Instead, they use their antennae to sense chemicals on surfaces and in the air. Ants’ antennae are porous like a kitchen sponge allowing chemicals to enter and activate receptors inside. You will often see ants tap each other with their antennae. That behavior, called antennation, helps them recognize nestmates who will share the same chemical nest signature.

---Can ants bite or sting?

Many ants will use their mandibles, or jaws, to defend themselves but that typically just feels like a pinch. Some ants have a stinger at the end of their abdomen that can deliver a venomous sting. While the type of venom can vary across species, many ants’ sting contains formic acid which causes a burning sensation. Some have special glands containing acid that can spray at attackers causing burning and alarming odors.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....947369/kidnapper-ant

---+ For more information:

Neil Tsutsui Lab of Evolution, Ecology and Behavior of Social Insects at the University of California, Berkeley

https://nature.berkeley.edu/tsutsuilab/

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to the following fans for correctly naming and describing the inter-species, mandible-to-mandible ant behavior we showed on our Deep Look Community Tab… "trophallaxis:"

Senpai

Ravinraven6913

CJ Thibeau

Maksimilian Tašler

Isha

https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UC-3SbfTPJsL8fJAPK

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Leonhardt Wille

Justin Bull

Bill Cass

Sarah Khalida Mohamad

Daniel Weinstein

Chris B Emrick

Karen Reynolds

Tea Torvinen

David Deshpande

Daisuke Goto

Companion Cube

WhatzGames

Richard Shalumov

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

Gerardo Alfaro

Robert Amling

Shirley Washburn

Robert Warner

Supernovabetty

johanna reis

Kendall Rasmussen

Pamela Parker

Sayantan Dasgupta

Joshua Murallon Robertson

Cindy McGill

Kenia Villegas

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

Aurora

Dean Skoglund

Silvan Wendland

Ivan Alexander

monoirre

Sonia Tanlimco

Two Box Fish

Jane Orbuch

Allen

Laurel Przybylski

Johnnyonnyful

Rick Wong

Levi Cai

Titania Juang

Nathan Wright

Carl

Michael Mieczkowski

Kyle Fisher

JanetFromAnotherPlanet

Kallie Moore

SueEllen McCann

Geidi Rodriguez

Louis O'Neill

Edwin Rivas

Jeanne Sommer

Katherine Schick

Aurora Mitchell

Cory

Ricardo Martinez

riceeater

Daisy Trevino

KW

PM Daeley

Joao Ascensao

Chris Murphy

Nicolette Ray

TierZoo

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

Jellyfish don’t have a heart, or blood, or even a brain. They’ve survived five mass extinctions. And you can find them in every ocean, from pole to pole. What’s their secret? Keeping it simple, but with a few dangerous tricks.

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

--- Why do Jellyfish Sting?

Jellyfish sting to paralyze their prey. They use special cells called nematocysts. Jellyfish don’t have a brain or a central nervous system to control these stinging cells, so each one has it’s own trip wire, called a cnidocil.

When triggered, the nematocyst cells act like a combination of fishing hook and hypodermic needle. They fire a barb into the flesh of the jellyfish’s prey at 10,000 times the force of gravity – making it one of the fastest mechanisms in the animal kingdom. As the barb latches on, a thread-like filament bathed in toxin erupts from the barb and delivers the poison.

The nematocyst only works if the barb can penetrate the skin, which is why some jellies are more dangerous to humans than others. The smooth-looking tentacles of a sea anemone (a close relative of jellies that also has nematocyst cells) feel like sandpaper to the touch. Their nematocysts are firing, but the barbs aren’t powerful enough to puncture your skin.

--- Read the article for this video on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....015/09/29/why-jellyf

--- More great DEEP LOOK episodes:

Pygmy Seahorses: Masters of Camouflage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3CtGoqz3ww

You're Not Hallucinating. That's Just Squid Skin.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0wtLrlIKvJE

The Fantastic Fur of Sea Otters

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zxqg_um1TXI

--- Related videos from the PBS Digital Studios Network!

I Don't Think You're Ready for These Jellies - It’s Okay to Be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a4DQQe5p5gc

Why Neuroscientists Love Kinky Sea Slugs - Gross Science

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QGHiyWjjhHY

What Physics Teachers Get Wrong About Tides! | Space Time

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pwChk4S99i4

--- More KQED SCIENCE:

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science: http://ww2.kqed.org/science

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

It's stealth, not speed that makes owls such exceptional hunters. Zoom way in on their phenomenal feathers to see what makes them whisper-quiet.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

--- How do owls hunt silently?

When birds flap their wings it creates turbulences in the air as it rushes over their wings. In general, the larger a bird is and the faster it flies, the larger the turbulence created and that means more sound.

The feathers at the leading edge of an owl’s wings have an unusual serrated appearance, referred to as a comb or fringe. The tiny hooked projections stick out and break up the wind as it flows over the owl’s wings reducing the size and sound of the turbulences.

Owl feathers go one step further to control sound. When viewed up-close, owl feathers appear velvety. The furry texture absorbs and dampens sound like a sound blanket. It also allows the feathers to quietly slide past each other in flight, reducing rusting sounds.

--- Why do owls hunt at night?

Owls belong to a group called raptors which also so includes with hawks, eagles and falcons. Most of these birds of prey hunt during the day and rely on. But unlike most other raptors, the roughly 200 species of owl are generally nocturnal while others are crepuscular, meaning that they’re active around dawn and dusk.

They have extremely powerful low-light vision, and finely tuned hearing which allows them to locate the source of even the smallest sound. Owls simply hide and wait for their prey to betray its own location. As ambush hunters, owls tend to rely on surprise more often than their ability to give chase.

--- Why do owls hoot?

With Halloween around the corner, you might have noticed a familiar sound in the night. It’s mating season for owls and the sound of their hooting fills the darkness.

According to Chris Clark, an an assistant professor of biology at UC Riverside,, “The reason why owls are getting ready to breed right now in the late fall is because they breed earlier than most birds. The bigger the bird the longer it takes for them to incubate their eggs and for the nestlings to hatch out and or the fledglings to leave the nest. Owls try to breed really early because they want their babies to be leaving the nest and practicing hunting right when there are lots of baby animals around like baby rabbits that are easy prey.”

--- More great DEEP LOOK episodes:

Halloween Special: Watch Flesh-Eating Beetles Strip Bodies to the Bone

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Np0hJGKrIWg

What Happens When You Put a Hummingbird in a Wind Tunnel?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JyqY64ovjfY

You're Not Hallucinating. That's Just Squid Skin.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0wtLrlIKvJE

--- Super videos from the PBS Digital Studios Network!

Did Dinosaurs Really Go Extinct? - It's Okay to be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3_RLz0whDv4

The Surprising Ways Death Shapes Our Lives - BrainCraft

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Joalg73L_gw

Crazy pool vortex - Physics Girl

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pnbJEg9r1o8

--- More KQED SCIENCE:

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Conceived in the open sea, tiny spaceship-shaped sea urchin larvae search the vast ocean to find a home. After this incredible odyssey, they undergo one of the most remarkable transformations in nature.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Every summer, millions of people head to the coast to soak up the sun and play in the waves. But they aren’t alone. Just beyond the crashing surf, hundreds of millions of tiny sea urchin larvae are also floating around, preparing for one of the most dramatic transformations in the animal kingdom.

Scientists along the Pacific coast are investigating how these microscopic ocean drifters, which look like tiny spaceships, find their way back home to the shoreline, where they attach themselves, grow into spiny creatures and live out a slow-moving life that often exceeds 100 years.“These sorts of studies are absolutely crucial if we want to not only maintain healthy fisheries but indeed a healthy ocean,” says Jason Hodin, a research scientist at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories.

http://staff.washington.edu/hodin/

http://depts.washington.edu/fhl/

Sea urchins reproduce by sending clouds of eggs and sperm into the water. Millions of larvae are formed, but only a handful make it back to the shoreline to grow into adults.

--- What are sea urchins?

Sea urchins are spiny invertebrate animals. Adult sea urchins are globe-shaped and show five-point radial symmetry. They move using a system of tube feet. Sea urchins belong to the phylum Echinodermata along with their relatives the sea stars (starfish), sand dollars and sea slugs.

--- What do sea urchins eat?

Sea urchins eat algae and can reduce kelp forests to barrens if their numbers grow too high. A sea urchin’s mouth, referred to as Aristotle’s lantern, is on the underside and has five sharp teeth. The urchin uses the tube feet to move the food to its mouth.

--- How do sea urchins reproduce?

Male sea urchins release clouds of sperm and females release huge numbers of eggs directly into the ocean water. The gametes meet and the sperm fertilize the eggs. The fertilized eggs grow into free-swimming embryos which themselves develop into larvae called plutei. The plutei swim through the ocean as plankton until they drop to the seafloor and metamorphosize into the globe-shaped adult urchins.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....016/08/23/sea-urchin

---+ For more information:

Marine Larvae Video Resource

http://marinedevelopmentresource.stanford.edu/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

From Drifter to Dynamo: The Story of Plankton | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jUvJ5ANH86I

Pygmy Seahorses: Masters of Camouflage | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3CtGoqz3ww

The Fantastic Fur of Sea Otters | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zxqg_um1TXI

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay To Be Smart: Can Coral Reefs Survive Climate Change?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P7ydNafXxJI

Gross Science: White Sand Beaches Are Made of Fish Poop

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1SfxgY1dIM4

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #seaurchin #urchins

Honey bees make honey from nectar to fuel their flight – and our sweet tooth. But they also need pollen for protein. So they trap, brush and pack it into baskets on their legs to make a special food called bee bread.

JOIN our Deep Look community on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Spring means honey bees flitting from flower to flower. This frantic insect activity is essential to growing foods like almonds, raspberries and apples. Bees move pollen, making it possible for plants to grow the fruit and seeds they need to reproduce.

But honey bees don’t just move pollen from plant to plant. They also keep a lot for themselves. They carry it around in neat little balls, one on each of their hind legs. Collecting, packing and making pollen into something they can eat is a tough, intricate job that’s essential to the colony’s well-being.

Older female adult bees collect pollen and mix it with nectar or honey as they go along, then carry it back to the hive and deposit it in cells next to the developing baby bees, called larvae. This stored pollen, known as bee bread, is the colony’s main source of protein.

“You don’t have bees flying along snacking on pollen as they’re collecting it,” said Mark Carroll, an entomologist at the US Department of Agriculture’s Carl Hayden Bee Research Center in Tucson. “This is the form of pollen that bees are eating.”

--- What is bee bread?

It’s the pollen that worker honey bees have collected, mixed with a little nectar or honey and stored within cells in the hive.

--- What is bee bread used for?

Bee bread is the main source of protein for adult bees and larvae. Young adult bees eat bee bread to make a liquid food similar to mammal’s milk that they feed to growing larvae; they also feed little bits of bee bread to older larvae.

--- How do honey bees use their pollen basket?

When a bee lands on a flower, it nibbles and licks off the pollen, which sticks to its head. It wipes the pollen off its eyes and antennae with a brush on each of its front legs, using them in tandem like windshield wipers. It also cleans the pollen off its mouth part, and as it does this, it mixes it with some saliva and a little nectar or honey that it carries around in a kind of stomach called a crop.

Then the bee uses brushes on its front, middle and hind legs to move the pollen, conveyor-belt style, front to middle to back. As it flies from bloom to bloom, the bee combs the pollen very quickly and moves it into baskets on its hind legs. Each pollen basket, called a corbicula, is a concave section of the hind leg covered by longish hairs that bend over and around the pollen.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....940898/honey-bees-ma

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to spqr0a, A D2, James Peirce, Armageddonchampion, and Даниил Мерзликин for identifying what our worker bee was putting in a honeycomb cell (and why) - Bee Bread! See more on our Community Tab: https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UC-3SbfTPJsL8fJAPK

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Ahegao Comics, Allen, Aurora Mitchell, Beckie, Ben Espey, Bill Cass, Breanna Tarnawsky, Carlos Zepeda, Chris B Emrick, Chris Murphy, Companion Cube, Cooper Caraway, Daisuke Goto, Daniel Weinstein, David Deshpande, Edwin Rivas, Elizabeth Ann Ditz, Elizabeth Wolden, Ivan Alexander, Iver Soto, Jane Orbuch, JanetFromAnotherPlanet, Jason Buberel, Jeanine Womble, Jenn's Bowtique, Jeremy Lambert, Jiayang Li, Joao Ascensao, johanna reis, Johnnyonnyful, Joshua Murallon Robertson, Justin Bull, Karen Reynolds, Kristell Esquivel , KW, Kyle Fisher, Laurel Przybylski, Levi Cai, Lyall Talarico, Mario Rahmani, Marjorie D Miller, Mark Joshua Bernardo, Michael Mieczkowski, Monica Albe, Nathan Padilla, Nathan Wright, Pamela Parker, PM Daeley, Ricardo Martinez, Robert Amling, Robert Warner, Sayantan Dasgupta, Sean Tucker, Shelley Pearson Cranshaw, Shirley Washburn, SueEllen McCann, Tatianna Bartlett, Tea Torvinen, TierZoo, Tommy Tran, Two Box Fish, WhatzGames, Willy Nursalim

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED. #honeybees #bee bread #deeplook

Join Deep Look on Patreon NOW!

https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Cone Snails have an arsenal of tools and weapons under their pretty shells. These reef-dwelling hunters nab their prey in microseconds, then slowly eat them alive.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

New research shows that cone snails — ocean-dwelling mollusks known for their brightly colored shells — attack their prey faster than almost any member of the animal kingdom.

There are hundreds of species of these normally slow-moving hunters found in oceans across the world. They take down fish, worms and other snails using a hollow, harpoon-like tooth that acts like a spear and a hypodermic needle. When they impale their prey, cone snails inject a chemical cocktail that subdues their meal and gives them time to dine at their leisure.

Cone snails launch their harpoons so quickly that scientists were previously unable to capture the movement on camera, making it impossible to calculate just how speedy these snails are. Now, using super-high-speed video, researchers have filmed the full flight of the harpoon for the first time.

From start to finish, the harpoon’s flight takes less than 200 micro-seconds. That’s one five-thousandth of a second. It launches with an acceleration equivalent to a bullet fired from a pistol.

So how do these sedentary snails pull off such a high-octane feat? Hydrostatic pressure — the pressure from fluid — builds within the half of the snail’s proboscis closest to its body, locked behind a tight o-ring of muscle. When it comes time to strike, the muscle relaxes, and the venom-laced fluid punches into the harpoon’s bulbous base. This pressure launches the harpoon out into the snail’s unsuspecting prey.

As fast as the harpoon launches, it comes to an even more abrupt stop. The base of the harpoon gets caught at the end of the proboscis so the snail can reel in its meal.

The high-speed action doesn’t stop with the harpoon. Cone snail venom acts fast, subduing fish in as little as a few seconds. The venom is filled with unique molecules, broadly referred to as conotoxins.

The composition of cone snail venom varies from species to species, and even between individuals of the same species, creating a library of potential new drugs that researchers are eager to mine. In combination, these chemicals work together to rapidly paralyze a cone snail’s prey. Individually, some molecules from cone snail venom can provide non-opioid pain relief, and could potentially treat Parkinson’s disease or cancer.

--- Where do cone snails live?

There are 500 species of cone snails living in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, the Caribbean and Red Seas, and the Florida coast.

--- Can cone snails kill humans?

Most of them do not. Only eight of those 500 species, including the geography cone, have been known to kill humans.

--- Why are scientists interested in cone snails?

Cone snail venom is derived from thousands of small molecules call peptides that the snail makes under its shell. These peptides produce different effects on cells, which scientists hope to manipulate in the treatment of various diseases.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://wp.me/p6iq8L-84uC

---+ For more information:

Here’s what WebMD says about treating a cone snail sting:

https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-g....uides/cone-snail-sti

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

This Mushroom Starts Killing You Before You Even Realize It

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bl9aCH2QaQY

Take Two Leeches and Call Me in the Morning

https://youtu.be/O-0SFWPLaII

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Space Time: Quantum Mechanics Playlist

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-IfmgyXs7z8&list=PLsPUh22kYmNCGaVGuGfKfJl-6RdHiCjo1

Above The Noise: Endangered Species: Worth Saving from Extinction?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h5eTqjzQZDY

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the Templeton Religion Trust and the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Pacific mole crabs, also known as sand crabs, make their living just under the surface of the sand, where they're safe from breaking waves and hungry birds. Some very special physics help them dig with astonishing speed.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Among the surfers and beach-casting anglers, there’s a new visitor to San Francisco’s Ocean Beach shoreline.

Benjamin McInroe is there for only one reason -- to find Pacific mole crabs, a creature commonly known as “sand crabs” -- and the tiny animals whose burrowing causes millions of small bubbles to appear on the beach as the tide comes in and out.

McInroe is a graduate student from UC Berkeley studying biophysics. He wants to know what makes these little creatures so proficient at digging their way through the wet sand.

McInroe hopes that he can one day copy their techniques to build a new generation of digging robots.

-- What are Pacific Mole Crabs?

Pacific mole crabs, also known as sand crabs, are crustaceans, related to shrimp and lobsters. They have four pairs of legs and one pair of specialized legs in the front called uropods that look like paddles for digging in sand. Pacific mole crabs burrow through wet sand and stick their antennae out to catch bits of kelp and other debris kicked up by the breaking waves.

-- What makes those holes in the sand at the beach?

When the waves recede, mole crabs burrow down into the sand to keep from being exposed. They dig tail-first very quickly leaving holes in the wet sand. The holes bubble as water seeps into the holes and the air escapes.

-- What do birds eat in the wet beach sand?

Shore birds like seagulls rush down the beach as the waves recede to catch mole crabs that haven’t burrowed down quickly enough to escape. The birds typically run or fly away as the next wave breaks and rolls in.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....018/02/13/for-pacifi

---+ For more information:

Benjamin McInroe, a Ph.D. student at UC Berkeley, studies how Pacific mole crabs burrow

https://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~bmcinroe/

Professor Robert Full directs the Poly-PEDAL Lab at UC Berkeley, where researchers study the physics of how animals and use that knowledge to build mechanical systems like robots based on their findings.

http://polypedal.berkeley.edu/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Decorator Crabs Make High Fashion at Low Tide | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/OwQcv7TyX04

These Fish Are All About Sex on the Beach | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/j5F3z1iP0Ic

Sea Urchins Pull Themselves Inside Out to be Reborn | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/ak2xqH5h0YY

There's Something Very Fishy About These Trees ... | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rZWiWh5acbE&t=1s

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Why Do We Eat Artificial Flavors? | Origin of Everything

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iNaJ31EV13U

The Facts About Dinosaurs & Feathers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOeFRg_1_Yg

Why Is Blue So Rare In Nature?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3g246c6Bv58

---+ Follow KQED Science

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

At night, these parasites crawl onto your bed, bite you and suck your blood. Then they find a nearby hideout where they leave disgusting telltale signs. But these pests have an Achilles’ heel that stops them cold.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Join our community on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Adult bed bugs are about the size and color of an apple seed. After biting, they hide in a nearby cranny, like the seam of the mattress.

At the University of California, Irvine, biologist and engineer Catherine Loudon is working to create synthetic surfaces that could trap bed bugs. She was inspired by the tiny hooked hairs that grow from the leaves of some varieties of beans, such as kidney and green beans. In nature, these hairs, called trichomes, pierce through the feet of the aphids and leafhoppers that like to feed on the plants.

Researchers have found that these pointy hairs are just as effective against bed bugs, even though the bloodsucking parasites don’t feed on leaves. Loudon’s goal is to mimic a bean leaf’s mechanism to create an inexpensive, portable bed bug trap.

“You could imagine a strip that would act as a barrier that could be placed virtually anywhere: across the portal to a room, behind the headboard, on subway seats, an airplane,” Loudon said. “They have six legs, so that’s six opportunities to get trapped.”

--- Where do bed bugs come from?

Bed bugs don’t fly or jump or come in from the garden. They crawl very quickly and hide in travelers’ luggage. They also move around on secondhand furniture, or from apartment to apartment.

--- How can I avoid bringing bed bugs home?

“It would probably be a prudent thing to do a quick bed check if you’re sleeping in a strange bed,” said Potter. His recommendation goes for hotel rooms, as well as dorms and summer camp bunk beds. He suggests pulling back the sheet at the head of the bed and checking the seams on the top and bottom of the mattress and the box spring.

---+ For more tips, read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....944245/watch-bed-bug

---+ More Great Deep Look Episodes:

‘Parasites are Dynamite’ Playlist: https://www.youtube.com/playli....st?list=PLdKlciEDdCQ

---+ ?Congratulations ?to the following fans for correctly identifying the creature's species name in our community tab challenge:

Stay in Your Layne

Brian Lee

Brad Denney

Elise Wade

Raminta’s Photography

https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UC-3SbfTPJsL8fJAPK

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Allen, Aurora Mitchell, Beckie, Ben Espey, Bill Cass, Bluapex, Breanna Tarnawsky, Carl, Chris B Emrick, Chris Murphy, Cindy McGill, Companion Cube, Cory, Daisuke Goto, Daisy Trevino , Daniel Voisine, Daniel Weinstein, David Deshpande, Dean Skoglund, Edwin Rivas, Elizabeth Ann Ditz, Eric Carter, Geidi Rodriguez, Gerardo Alfaro, Ivan Alexander, Jane Orbuch, JanetFromAnotherPlanet, Jason Buberel, Jeanine Womble, Jeanne Sommer, Jiayang Li, Joao Ascensao, johanna reis, Johnnyonnyful, Joshua Murallon Robertson, Justin Bull, Kallie Moore, Karen Reynolds, Katherine Schick, Kendall Rasmussen, Kenia Villegas, Kristell Esquivel, KW, Kyle Fisher, Laurel Przybylski, Levi Cai, Mark Joshua Bernardo, Michael Mieczkowski, Michele Wong, Nathan Padilla, Nathan Wright, Nicolette Ray, Pamela Parker, PM Daeley, Ricardo Martinez, riceeater, Richard Shalumov, Rick Wong, Robert Amling, Robert Warner, Samuel Bean, Sayantan Dasgupta, Sean Tucker, Shelley Pearson Cranshaw, Shirley Washburn, Sonia Tanlimco, SueEllen McCann, Supernovabetty, Tea Torvinen, TierZoo, Titania Juang, Two Box Fish, WhatzGames, Willy Nursalim, Yvan Mostaza

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

#bedbug #bedbugtrap #bedbugbite

They may look serene as they glide across the surface of a stream, but don't be fooled by water striders. They're actually searching for prey for whom a babbling brook quickly becomes an inescapable death trap.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

With the drought officially over and the summer heat upon us, people all across California are heading outdoors. For many, that means a day on the river or relaxing by the lake. The wet winter means there’s plenty of habitat for one of nature’s most curious creatures.

Water striders, also called pond skaters, seem to defy gravity. You’ve probably seen them flitting across the water’s surface, dodging ripples as they patrol streams and quiet backwater eddies.

Scientists like David Hu at Georgia Institute of Technology study how water striders move and how they make their living as predators lurking on the water’s surface. It’s an amazing combination of biology and physics best understood by looking up close. Very close.

--- What are water striders?

The common water strider (Gerris lacustris) is an insect typically found in slowly moving freshwater streams and ponds. They are able to move on the water's surface without sinking. They are easy to spot because they create circular waves on the surface of the water.

--- How do water striders walk on water?

Water tends to stick to itself (cohesion), especially at the surface where it meets the air (surface tension). Water striders don’t weigh very much and they spread their weight out with their long legs. Striders are also covered in microscopic hairs called micro-setae that repel water. Instead of sinking into the water, their legs push down and create dimples.

--- What do water striders eat?

Water striders are predators and scavengers. They use their ability to walk on water to their advantage, primarily eating other insects that fall into the water at get trapped by the surface tension. A water strider uses its tube-shaped proboscis to penetrate their prey’s exoskeleton, inject digestive enzymes and suck out the prey’s pre-digested innards.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/08/01/this-is-wh

---+ For more information:

http://www.nature.com/nature/j....ournal/v424/n6949/ab

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

These Fish Are All About Sex on the Beach | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j5F3z1iP0Ic&list=PLdKlciEDdCQDxBs0SZgTMqhszst1jqZhp&index=3

How Do Pelicans Survive Their Death-Defying Dives? | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BfEboMmwAMw

Decorator Crabs Make High Fashion at Low Tide | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OwQcv7TyX04

Why Is The Very Hungry Caterpillar So Dang Hungry? | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=el_lPd2oFV4&list=PLdKlciEDdCQDxBs0SZgTMqhszst1jqZhp

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Beavers: The Smartest Thing in Fur Pants | It’s Okay To Be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zm6X77ShHa8

Can Genetically Engineered Mosquitoes Help Fight Disease? | Above The Noise

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CB_h7aheAEM

How Do Glaciers Move? | It’s Okay To Be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RnlPrdMoQ1Y

Your Biological Clock at Work | BrainCraft

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Q8djfQlYwQ

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate based in San Francisco, serves the people of Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial media. Home to one of the most listened-to public radio station in the nation, one of the highest-rated public television services and an award-winning education program, KQED is also a leader and innovator in interactive media and technology, taking people of all ages on journeys of exploration — exposing them to new people, places and ideas.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Straight out of science fiction, the fearsome wormlion ambushes prey at the bottom of a tidy - and terrifying - sand pit, then flicks their carcasses out. These meals fuel its transformation into something unexpected.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Join our community on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

---

Ominous creatures that lurk deep underground in the desert, like the sandworms in the classic science fiction novel "Dune," aren’t just make-believe. For ants and other prey, wormlions are a terrifying reality.

While quite small—they can grow up to an inch—wormlions are fly larvae that curl up their bodies like slingshots. Usually found under rock or log overhangs in dry, sandy landscapes, they’ll energetically fling soil, sand and pebbles out of the way to dig pit traps.

Once an unlucky critter falls in, wormlions move at lightning speed and quickly wrap their bodies around their victims. Squeezing them like boa constrictors, they also inject them with a paralyzing venom. They feed this way for several years, until they transform into adults.

Joyce Gross, a computer programmer for the UC Berkeley Natural History Museums, is fascinated by their unique hunting behavior.

“They have such a weird life history," she said. "They're the only flies that dig pits like this, and wait for prey to fall in, just like antlions.”

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....941850/meeting-a-wor

--- Are antlions and wormlions related?

While they use a similar hunting technique with pitfall traps, they’re actually two separate species.

--- How are antlions and wormlions different from each other?

Antlions have big jaws, while wormlions have tiny mouthparts typical of other flies. They also dig pits differently. Antlions (genus Myrmeleon) create deeper pits by digging backwards in a spiral-shaped path.

---+ For more information:

Read "Demons of the Dust" (1930) by William Morton Wheeler: https://books.google.com/books..../about/Demons_of_the

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Creepy Crawly Videos: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yb26BBvAAWU&list=PLdKlciEDdCQBYF3x2RYLhPH0-tP_u2nRX

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to the following fans for correctly identifying the creature's genus in our community tab challenge: Gar Báge, Phil Conti, Pikaia Battaile, Trinidadmax, and BorderLander .

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

ThePeaceOfBread, Jeremy Gutierrez, Bill Cass, Justin Bull, Daniel Weinstein, Chris B Emrick, Karen Reynolds, Tea Torvinen, m_drunk, David Deshpande, Noah Hess, Daisuke Goto, Companion Cube, WhatzGames, Edwin, ThePeaceOfBread, Richard Shalumov, Elizabeth Ann Ditz, pearsryummy, Samuel Bean, Shirley Washburn, Kristell Esquivel , Jiayang Li, Jeremy Gutierrez, Carlos Zepeda, KW, johanna reis, Robert Warner, Monica Albe, Elizabeth Wolden, Cindy McGill, Sayantan Dasgupta, Robert Amling, Kilillith, Shelley Pearson Cranshaw, Pamela Parker, Kendall Rasmussen, Joshua Murallon Robertson, Kenia Villegas, Breanna Tarnawsky, Sonia Tanlimco, Bluapex, Ivan Alexander, Allen, Michele Wong, Johnnyonnyful, Tommy Tran, Rick Wong, Dean Skoglund, Laurel Przybylski, Levi Cai, Beckie, Jane Orbuch, Nathan Wright, Nathan Padilla, Jason Buberel, Sean Tucker, Carl, Mark Joshua Bernardo, Titania Juang, Daniel Voisine, Michael Mieczkowski, Kyle Fisher, Kirtan Patel, Jeanine Womble, JanetFromAnotherPlanet, Kallie Moore, SueEllen McCann, Jeanne Sommer, Edwin Rivas, Geidi Rodriguez, Benjamin Ip, Willy Nursalim, Katherine Schick, Aurora Mitchell, Two Box Fish, Daisy Trevino , Ricardo Martinez, Marjorie D Miller, Ben Espey, Cory, Eric Carter, PM Daeley, Ahegao Comics, Iver Soto, Chris Murphy, Joao Ascensao, Nicolette Ray, Yvan Mostaza, TierZoo, Gerzon

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the Templeton Religion Trust, the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#wormlion #insect #deeplook

Male side-blotched lizards have more than one way to get the girl. Orange males are bullies. Yellows are sneaks. Blues team up with a buddy to protect their territories. Who wins? It depends - on a genetic game of roshambo.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Every spring, keen-eyed biologists carrying fishing poles search the rolling hills near Los Banos, about two hours south of San Francisco. But they’re not looking for fish. They’re catching rock-paper-scissors lizards.

The research team collects Western side-blotched lizards, which come in different shades of blue, orange and yellow.

Barry Sinervo, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz, leads the team. Their intricate mating strategies reminded the the researchers of the rock-paper-scissors game where rock beats scissors, scissors beats paper and paper beats rock.

It’s all about territories. Orange males tend to be the biggest and most aggressive. They hold large territories with several females each and are able to oust the somewhat smaller and less aggressive blues. Blue males typically hold smaller territories and more monogamous, each focusing his interest on a single female. Yellow males tend not to even form exclusive territories Instead they use stealth to find unaccompanied females with whom to mate.

The yellow males are particularly successful with females that live in territories held by their more aggressive orange competitors. Because the orange males spread their attention among several females, they aren’t able to guard each individual female against intruding yellow males. But the more monogamous blues males are more vigilant and chase sneaky yellow males away.

Their different strategies keep each other in check making the system stable. Sinervo believes this game has likely been in play for at least 15 million years.

--- How do side-blotched lizards choose a mate?

The males compete with each other, sometimes violently, for access to females. The females generally prefer males of their own color but also give preference to whichever color male is more rare that mating season.

--- Why do lizards do push up and down?

Male lizards do little pushups as a territorial display meant to tell competitors to back off. It’s best to use a warning instead of fighting right away because there’s always a danger of getting hurt in a fight. Some lizards like side-blotched lizards also use slow push ups to warn their neighbors of an incoming threat.

--- Why do side-blotched lizards fight?

Sometimes aggressive territorial displays are not enough to dissuade invaders so side-blotched lizards will resort to fighting. They have small sharp teeth and will lunge at each other inflicting bites and headbutts.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science: https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....016/05/17/these-liza

---+ For more information:

The Lab of Dr. Barry Sinervo, LizardLand, University of California, Santa Cruz http://bio.research.ucsc.edu/~....barrylab/lizardland/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Meet the Dust Mites, Tiny Roommates That Feast On Your Skin

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ACrLMtPyRM0

Stinging Scorpion vs. Pain-Defying Mouse

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w-K_YtWqMro

These Crazy Cute Baby Turtles Want Their Lake Back

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YTYFdpNpkMY

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay to Be Smart: The Cosmic Afterglow

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZvrHL7-c1Ys

It's Okay to Be Smart: The Most Important Moment in the History of Life

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jf06MlX8yik

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate based in San Francisco, serves the people of Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial media. KQED is also a leader and innovator in interactive media and technology, taking people of all ages on journeys of exploration — exposing them to new people, places and ideas.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #lizards #rockpaperscissorslizardspock

Their skeletons are prized by beachcombers, but sand dollars look way different in their lives beneath the waves. Covered in thousands of purple spines, they have a bizarre diet that helps them exploit the turbulent waters of the sandy sea floor.

Please follow us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Pristine white sand dollars have long been the souvenir to commemorate a successful day at the beach. But most people who pick them up don’t realize that they’ve collected the skeleton of an animal, washed up at the end of a long life.

As it turns out, scientists say there’s a lot to be said about a sand dollar’s life. That skeleton -- also known as a test -- is really a tool, a remarkable feat of engineering that allows sand dollars to thrive on the shifting bottom of the sandy seafloor, an environment that most other sea creatures find inhospitable.

“They've done something really amazing and different,” said Rich Mooi, a researcher with the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. “They’re a pile of novelties, and they’ve gone way off the deep end in modifying their bodies to adapt to where they live.”

Mooi studies echinoderms, a word that roughly translates to “hedgehog skin.” It’s an aptly-fitting name for a group that includes sea urchins, sand dollars, sea stars and sea cucumbers. But Mooi says sand dollars really have his heart, in part because of their incredible adaptations.

--- What are sand dollars?

Sand dollars belong to a group of animals called Echinoderms that includes some more familiar animals like starfish and sea urchins. Sand dollars are actually a type of flattened sea urchin with miniaturized spines and tube feet more suited to sandy seafloors.

--- What do sand dollars eat?

Sand dollars consume sand but they get actual nutrition from the layer of algae and bacteria that coat the grains, not the sand itself.

--- Are sand dollars alive? Why do they Turn White?

When sand dollars are alive, they are covered in tiny tube feet and spines that make them appear like fuzzy discs. When they die, they lose their spines and tube feet exposing their white skeleton that scientists call a test. That skeleton is typically what people find on the beach.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....932072/a-sand-dollar

---+ For more information:

Learn more about Chris Lowe’s work with plankton including sand dollars and their relatives

http://lowe.stanford.edu/

Rich Mooi’s research into sand dollars for California Academy of Sciences

https://www.calacademy.org/lea....rn-explore/science-h

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

The Amazing Life of Sand | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/VkrQ9QuKprE

For Pacific Mole Crabs It's Dig or Die | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/tfoYD8pAsMw

This Adorable Sea Slug is a Sneaky Little Thief | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KLVfWKxtfow&t=112s

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

These Tiny Cells Shape Your Life | BrainCraft

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fnx-Qvx_fA8

What are Eye Boogers? | Reactions

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w3M8p-QCC7I

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the Templeton Religion Trust and the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

---+ SHOUT OUTS

Here are the winners from our episode image quiz posted in our channel Community Tab:

https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UC-3SbfTPJsL8fJAPK

?#1: Tektyx

Was the first to correctly ID the creature in our episode was a sand dollar.

?#2: tichu7

Was the first to ID what kind of sand dollar it was, the Pacific sand dollar.

?#3: Miguel Gomez

Also posted what kind of sand dollar it was was, but by another name: Eccentric sand dollar.

?#4: Gir Gremlin

The first viewer to identify the sand dollar by its scientific name: Dendraster excentricus!

Plenty of animals build their homes in oak trees. But some very teeny, tricky wasps make the tree do all the work. And each miniature mansion the trees build for the wasps' larvae is weirder and more flamboyant than the next.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

“What nerve!” you might say. What… gall! And you’d be right. The wasps are called gall-inducers.

---+ What do oak galls look like?

If you’ve ever spent a Summer or Fall around oak trees – such as the stalwart Valley Oak – Quercus lobata, or the stately Blue Oak, Quercus douglasii – you may be familiar with the large, vaguely fruity-looking objects clinging to the branches and leaves. Commonly called oak apples, these growths are the last thing you’d want to put in your mouth. They are intensely bitter, loaded with tannin compounds – the same compounds that in modest amounts give red wine its pleasant dryness, and tea its refreshing earthy tang.

That said, the oak apple’s powerful astringency has been prized for millennia. Tanning leather, making ink or dye, and cleaning wounds have been but a few of the gall’s historical uses.

But on closer inspection of these oaks – and many other plants and trees such as willows, alders, manzanitas, or pines – you can find a rogue’s gallery of smaller galls. Carefully peeking under leaves, along the stems and branches, or around the flower buds and acorns will likely lead you to unexpected finds. Smooth ones. Spiky ones. Long skinny ones, flat ones, lumpy, boxy ones. From the size of a golf ball down to that of a poppy seed. These structures wear shades of yellow, green, brown, purple, pink and red – and sometimes all of the above. A single tree may be host to dozens of types of gall, each one caused by a specific organism. And their shapes range from the sublime to the downright creepy. One tree may be encrusted with them, like a Christmas tree laden with ornaments and tinsel; and the next tree over may be almost completely free of galls. Why? It’s a mystery.

---+ How do oak galls form?

Galls are generally formed when an insect, or its larvae, introduce chemicals into a specific location, to push the plant’s growth hormones into overdrive. This can result in a great profusion of normal cells, increased size of existing cells, or the alteration of entire plant structures into new, alien forms.

Lots of creatures cause them; midges, mites, aphids, flies, even bacteria and viruses. But the undisputed champs are a big family of little wasps called Cynipids– rarely exceeding the size of a mosquito, a quarter of an inch in length.

“These tiny wasps cannot sting,” says Dr. Kathy Schick, Assistant Specialist/Curatorial Assistant at the Essig Museum of Entomology at UC Berkeley. “Gall-inducers are fascinating in that they are very specialized to their organ of the host plant.”

---+ What are oak galls?

These wasp houses are not homes exactly, but more akin to nurseries. The galls serve as an ideal environment for wasp larvae, whether it is a single offspring, or dozens. The tree is tricked into generating outsize amounts of soft, pillowy tissue inside each gall, on which the larvae gladly gorge themselves as they grow.

Full article: http://blogs.kqed.org/science/....2014/11/18/what-gall

---+ See more great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay to Be Smart: Inside the World of Fire Ants!

https://youtu.be/rz3UdLEWQ60

Gross Science: Can Spider Venom Cure Erectile Dysfunction?

https://youtu.be/5i9X8h17VNM

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

These Lizards Have Been Playing Rock-Paper-Scissors for 15 Million Years

https://youtu.be/rafdHxBwIbQ

Stinging Scorpion vs. Pain-Defying Mouse

https://youtu.be/w-K_YtWqMro

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Argentine ants are spreading across the globe, eliminating local ants with their take-no-prisoners tactics: invade, dismember, repeat. But this ruthless killer seems to have met its match in the winter ant, a California native with a formidable secret weapon.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

--- About Argentine Ants and Winter Ants

For about 200 years, the Argentine ant expansion story has been the slow-moving train wreck of myrmecology, the study of ants.

Wherever they go, Argentine ants eliminate the competition with a take-no-prisoners approach. Invade, attack, dismember, consume. Repeat. The basic wisdom among ant scientists is that if you see Argentines, it’s already too late.

As early as the 1970s, scientists began to notice a peculiar fact about the Argentine ant. Usually, when ants from different colonies are put together, even from the same species, they fight. But Argentine worker ants can be combined from colonies in Spain, Japan and California, and they will recognize each other — they won’t fight.

Without this natural check, researchers say, a single colony of ants from Argentina has spread across continents and oceans.

But Jasper Ridge near Stanford is different. In 1993, ant biologist Deborah Gordon’s laboratory began tracking ant populations there. Jasper Ridge was unconquered territory for the Argentines, but they already had been spotted.

The Ph.D students conducting field research began to notice one species of native ant was holding its own inside the boundary of the Argentine advance. What, the Stanford researchers wondered, was different here?

In 2008, students in Gordon’s invasion ecology class studying the ants claimed to have made a novel discovery. The students watched the winter ants wave their abdomens at their enemies, known as “gaster-flagging” in ant circles, before a cloudy liquid blob appeared at the tip.

Approaching the secretion sent the Argentines reeling away. Touching it could kill them. Over the next two years, the students repeated and studied the winter ant’s apparently novel defensive behavior. They also analyzed the secretion. (Turns out it comes from the same gland used by the ants’ ancestors, wasps, to sting.)

They confirmed that in fact, with this amazing defense, the preserve’s winter ants were not only surviving, they’re now pushing back, opening up space for other native ant populations to rebound.

--- Do Argentine ants bite?

Not people. Too small to hurt a human, they’re far more dangerous to their competitors, from other ants about their size to some small birds(!).

--- How do you kill Argentine ants?

Pest control companies usually recommend slow-acting, fat or protein-based bait that allows the workers to carry the poison back to the nest.

--- Why are winter ants called that?

In areas where temperatures dip below freezing, winter ants remain active while most ant species hibernate.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

http://ww2.kqed.org/science/20....16/05/03/winter-is-c

---+ For more information:

Gordon Lab’s at Stanford University: http://web.stanford.edu/~dmgordon/

Neil Tsutsui Lab’s at Berkeley: https://ourenvironment.berkele....y.edu/people/neil-ts

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes: