Top Vídeos

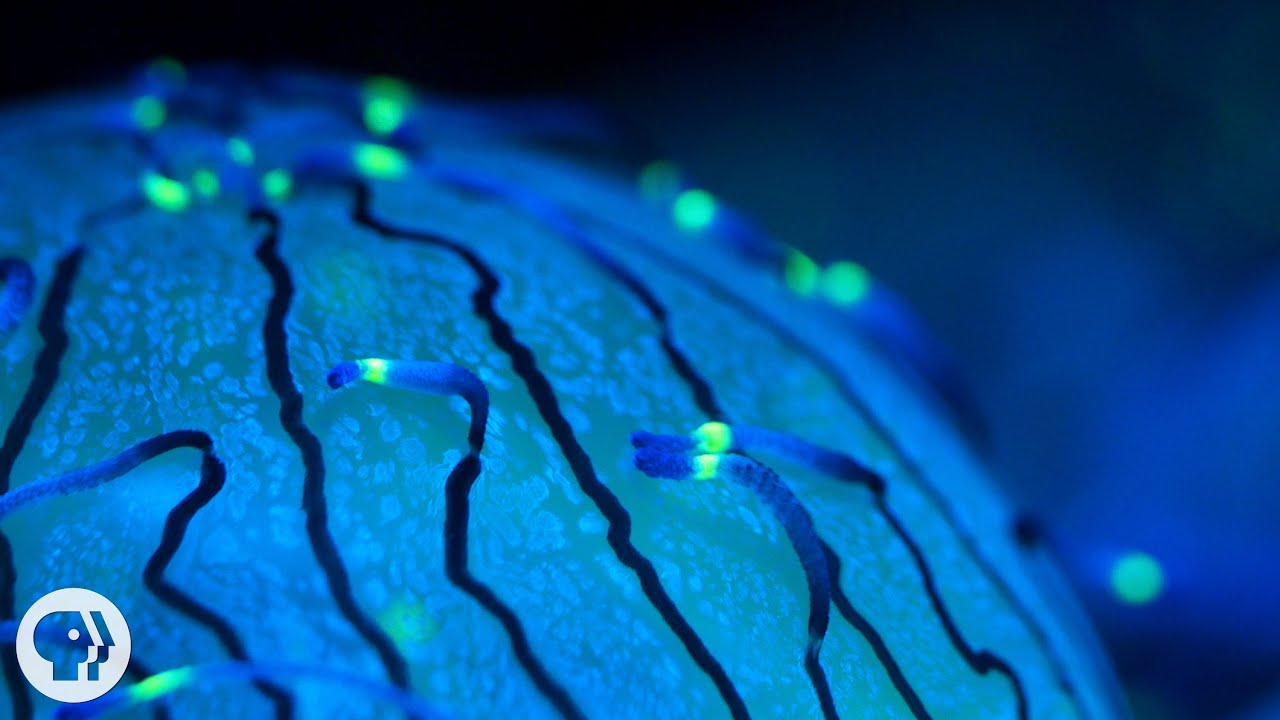

Jellyfish don’t have a heart, or blood, or even a brain. They’ve survived five mass extinctions. And you can find them in every ocean, from pole to pole. What’s their secret? Keeping it simple, but with a few dangerous tricks.

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

--- Why do Jellyfish Sting?

Jellyfish sting to paralyze their prey. They use special cells called nematocysts. Jellyfish don’t have a brain or a central nervous system to control these stinging cells, so each one has it’s own trip wire, called a cnidocil.

When triggered, the nematocyst cells act like a combination of fishing hook and hypodermic needle. They fire a barb into the flesh of the jellyfish’s prey at 10,000 times the force of gravity – making it one of the fastest mechanisms in the animal kingdom. As the barb latches on, a thread-like filament bathed in toxin erupts from the barb and delivers the poison.

The nematocyst only works if the barb can penetrate the skin, which is why some jellies are more dangerous to humans than others. The smooth-looking tentacles of a sea anemone (a close relative of jellies that also has nematocyst cells) feel like sandpaper to the touch. Their nematocysts are firing, but the barbs aren’t powerful enough to puncture your skin.

--- Read the article for this video on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....015/09/29/why-jellyf

--- More great DEEP LOOK episodes:

Pygmy Seahorses: Masters of Camouflage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3CtGoqz3ww

You're Not Hallucinating. That's Just Squid Skin.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0wtLrlIKvJE

The Fantastic Fur of Sea Otters

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zxqg_um1TXI

--- Related videos from the PBS Digital Studios Network!

I Don't Think You're Ready for These Jellies - It’s Okay to Be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a4DQQe5p5gc

Why Neuroscientists Love Kinky Sea Slugs - Gross Science

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QGHiyWjjhHY

What Physics Teachers Get Wrong About Tides! | Space Time

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pwChk4S99i4

--- More KQED SCIENCE:

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science: http://ww2.kqed.org/science

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

We've all heard that each and every snowflake is unique. But in a lab in sunny southern California, a physicist has learned to control the way snowflakes grow. Can he really make twins?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

California's historic drought is finally over thanks largely to a relentless parade of powerful storms that have brought the Sierra Nevada snowpack to the highest level in six years, and guaranteed skiing into June. All that snow spurs an age-old question -- is every snowflake really unique?

“It’s one of these questions that’s been around forever,” said Ken Libbrecht, a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “I think we all learn it in elementary school, the old saying that no two snowflakes are alike.”

--- How do snowflakes form?

Snow crystals form when humid air is cooled to the point that molecules of water vapor start sticking to each other. In the clouds, crystals usually start forming around a tiny microscopic dust particle, but if the water vapor gets cooled quickly enough the crystals can form spontaneously out of water molecules alone. Over time, more water molecules stick to the crystal until it gets heavy enough to fall.

--- Why do snowflakes have six arms?

Each water molecule is each made out of one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms. As vapor, the water molecules bounce around slamming into each other. As the vapor cools, the hydrogen atom of one molecule forms a bond with the oxygen of another water molecule. This is called a hydrogen bond. These bonds make the water molecules stick together in the shape of a hexagonal ring. As the crystal grows, more molecules join fitting within that same repeating pattern called a crystal array. The crystal keeps the hexagonal symmetry as it grows.

--- Is every snowflake unique?

Snowflakes develop into different shapes depending on the humidity and temperature conditions they experience at different times during their growth. In nature, snowflakes don’t travel together. Instead, each takes it’s own path through the clouds experiencing different conditions at different times. Since each crystal takes a different path, they each turn out slightly differently. Growing snow crystals in laboratory is a whole other story.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/04/11/identical-

---+ For more information:

Ken Libbrecht’s online guide to snowflakes, snow crystals and other ice phenomena.

http://snowcrystals.com/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Can A Thousand Tiny Swarming Robots Outsmart Nature? | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dDsmbwOrHJs

What Gives the Morpho Butterfly Its Magnificent Blue? | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=29Ts7CsJDpg&list=PLdKlciEDdCQDxBs0SZgTMqhszst1jqZhp&index=48

The Amazing Life of Sand | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VkrQ9QuKprE&list=PLdKlciEDdCQDxBs0SZgTMqhszst1jqZhp&index=51

The Hidden Perils of Permafrost | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wxABO84gol8

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

The Science of Snowflakes | It’s OK to be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fUot7XSX8uA

An Infinite Number of Words for Snow | PBS Idea Channel

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CX6i2M4AoZw

Is an Ice Age Coming? | Space Time | PBS Digital Studios

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ztninkgZ0ws

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Why are itchy lice so tough to get rid of and how do they spread like wildfire? They have huge claws that hook on hair perfectly, as they crawl quickly from head to head.

JOIN our Deep Look community on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is an ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Head lice can only move by crawling on hair. They glue their eggs to individual strands, nice and close to the scalp, where the heat helps them hatch. They feed on blood several times a day. And even though head lice can spread by laying their eggs in sports helmets and baseball caps, the main way they get around is by simply crawling from one head to another using scythe-shaped claws.

These claws, which are big relative to a louse’s body, work in unison with a small spiky thumb-like part called a spine. With the claw and spine at the end of each of its six legs, a louse grasps a hair strand to hold on, or quickly crawl from hair to hair like a speedy acrobat.

Their drive to stay on a human head is strong because once they’re off and lose access to their blood meals, they starve and die within 15 to 24 hours.

--- How do you kill lice?

Researchers found in 2016 that lice in the U.S. have become resistant to over-the-counter insecticide shampoos, which contain natural insecticides called pyrethrins, and their synthetic version, known as pyrethroids.

Other products do still work against lice, though. Prescription treatments that contain the insecticides ivermectin and spinosad are effective, said entomologist John Clark, of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. They’re prescribed to kill both lice and their eggs. Clark said treatments such as suffocants, which block the lice’s breathing holes, and hot-air devices that dry them up, also work. He added that tea tree oil works both as a repellent and a “pretty good” insecticide. Combing lice and eggs out with a special metal comb is also a recommended treatment.

--- How long do lice survive?

It takes six to nine days for their eggs to hatch and about as long for the young lice to grow up and start laying their own eggs. Adult lice can live on a person’s head for up to 30 days, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

--- Can your pet give you lice?

No. Human head lice only live on our heads. They can’t really move to other parts of our body or onto pets.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....939435/how-lice-turn

---+ For more information:

Visit the CDC’s page on head lice: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/head/index.html

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

How Mosquitoes Use Six Needles to Suck Your Blood:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rD8SmacBUcU

How Ticks Dig In With a Mouth Full of Hooks:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_IoOJu2_FKE

---+ Shoutout!

Congratulations to ?HaileyBubs, Tiffany Haner, cjovani78z, יואבי אייל, and Bellybutton King?, who were the first to correctly ID the species and subspecies of insect in this episode over at the Deep Look Community Tab:

https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UC-3SbfTPJsL8fJAPK

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Bill Cass, Justin Bull, Daniel Weinstein, David Deshpande, Daisuke Goto, Karen Reynolds, Yidan Sun, Elizabeth Ann Ditz, KW, Shirley Washburn, Tanya Finch, johanna reis, Shelley Pearson Cranshaw, Johnnyonnyful, Levi Cai, Jeanine Womble, Michael Mieczkowski, TierZoo, James Tarraga, Willy Nursalim, Aurora Mitchell, Marjorie D Miller, Joao Ascensao, PM Daeley, Two Box Fish, Tatianna Bartlett, Monica Albe, Jason Buberel

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the Templeton Religion Trust, the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

With their big heads and beady black eyes, Jerusalem crickets aren't winning any beauty contests. But that doesn't stop them from finding mates. They use their bulbous bellies to serenade each other with some furious drumming.

Support Deep Look on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Come join us on our Deep Look Communty Tab: https://www.youtube.com/user/K....QEDDeepLook/communit

--

DEEP LOOK is an ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Potato Bug. Child of the Earth. Old Bald-Headed Man. Skull Insects. Devil’s Baby. Spawn of Satan. There’s a fairly long list of imaginative nicknames that refer to Jerusalem crickets, those six-legged insects with eerily humanlike faces and prominent striped abdomens. And they can get quite large, too: Some measure over 3 inches long and weigh more than a mouse, so they can be quite unnerving if you see them crawling around in your backyard in summertime.

One individual who finds them compelling, and not creepy, has been studying Jerusalem crickets for over 40 years: David Weissman, a research associate in entomology affiliated with the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. He’s now considered the world’s foremost expert, since no one else has been as captivated or singlemindedly devoted to learning more about them.

While much of their general behavior is still not widely understood, Jerusalem crickets typically live solitary lives underground. They’ll emerge at night to scavenge for roots, tubers and smaller insects for their meals. And it’s also when they come out to serenade potential partners with a musical ritual: To attract a mate, adult crickets use their abdomens to drum the ground and generate low-frequency sound waves.

If a male begins drumming and a female senses the vibrations, she’ll respond with a longer drumming sequence so that he’ll have enough time to track her down. The drumming can vary between one beat every other second up to 40 beats per second.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....932923/jerusalem-cri

---+ For more information:

JERUSALEM! CRICKET? (Orthoptera: Stenopelmatidae: Stenopelmatus); Origins of a Common Name https://goo.gl/Y49GAK

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

The House Centipede is Fast, Furious, and Just So Extra | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/q2RtbP1d7Kg

Roly Polies Came From the Sea to Conquer the Earth | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/sj8pFX9SOXE

Turret Spiders Launch Sneak Attacks From Tiny Towers | Deep Look

https://youtu.be/9bEjYunwByw

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ? to Piss Dog, Trent Geer, Mario Stankovski, Jelani Shillingford,

and Chaddydaddy who were the first to correctly 3 the species of Jerusalem Cricket relatives of the Stenopelmatoidea superfamily in our episode, over at the Deep Look Community Tab:

https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UC-3SbfTPJsL8fJAPK

(hat tip to Antonio Garcia, who shared 3 full species names)

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the Templeton Religion Trust, the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation and the members of KQED. #deeplook #jerusalemcrickets #wildlife

Rain falls and within seconds dried-up moss that's been virtually dead for decades unfurls in an explosion of green. The microscopic creatures living in the moss come out to feed. Scientists say the genes in these “resurrection plants” might one day protect crops from drought.

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

How does moss grow?

Mosses don’t have roots. Their porous cells absorb water like a sponge, whenever it’s available.

When there’s no rain, mosses dry out completely and stop photosynthesizing. That is, they stop using carbon dioxide and the light of the sun to grow. They’re virtually dead, reduced to a pile of chemicals, and can stay that way for years. Researchers have found dry, 100-year-old moss samples in a museum that came back to life when water was added.

Read an extended article on how scientists hope to use resurrection plants to create crops that can survive drought:

http://ww2.kqed.org/science/20....15/06/25/these-resur

--

More great Deep Look episodes:

Where Are the Ants Carrying All Those Leaves?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-6oKJ5FGk24

What Happens When You Put a Hummingbird in a Wind Tunnel?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JyqY64ovjfY

Pygmy Seahorses: Masters of Camouflage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3CtGoqz3ww

See also another great video from the PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay to Be Smart: Where Does the Smell of Rain Come From?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lGcE5x8s0B8

KQED Science: http://ww2.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Please follow us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Take the PBSDS survey: https://to.pbs.org/2018YTSurvey

CORRECTION, 9/26/2018: This episode of Deep Look contains an error in the scientific name of the house centipede. It is Scutigera coleoptrata, not coleoptera. We regret the error. The viewers who caught the mistake will receive a free Deep Look T-shirt, and our gratitude. Thanks for keeping tabs on us!

Voracious, venomous and hella leggy, house centipedes are masterful predators with a knack for fancy footwork. But not all their legs are made for walking, they put some to work in other surprising ways.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Recognizable for their striking (some might say, repulsive) starburst-like shape, house centipedes have far fewer than the 100 legs their name suggests. They’re born with a modest eight, a count that grows to 30 as they reach adulthood.

If 30 legs sound like more than one critter really needs – perhaps it is. Over the last 450 million years or so, when centipedes split off from other arthropods, evolution has turned some of those walking limbs into other useful and versatile tools.

When it hunts, for example, the house centipede uses its legs as a rope to restrain prey in a tactic called “lassoing.” The tip of each leg is so finely segmented and flexible that it can coil around its victim to prevent escape.

The centipede’s venom-injecting fangs, called forciples, are also modified legs. Though shorter and thicker than the walking limbs, they are multi-jointed , which makes them far more dexterous than the fangs of insects and spiders, which hinge in only one plane.

Because of this dexterity, the centipede’s forciples not only inject venom, but also hold prey in place while the centipede feeds. Then they take a turn as a grooming tool. The centipede passes its legs through the forciples to clean and lubricate their sensory hairs.

Scientists have long noticed that because of their length and the fact that the centipede holds them aloft when it walks, these back legs give the appearance of a second pair antennae. The house centipede looks like it has two heads.

In evolution, when an animal imitates itself, it’s called automimicry. Automimicry occurs in some fish, birds and butterflies, and usually serves to divert predators.

New research suggests that’s not the whole story with the house centipede. Electron microscopy conducted on the centipede’s legs has revealed as many sensory hairs, or sensilla, on them as on the antennae.

The presence of so many sensory hairs suggest the centipede’s long back legs are not merely dummies used in a defensive ploy, but serve a special function, possibly in mate selection. During courtship, both the male and female house centipede slowly raise and lower their antennae and back legs, followed by mutual tapping and probing.

--- Are house centipedes dangerous?

Though they do have venom, house centipedes don’t typically bite humans.

--- Where do house centipedes live?

House centipedes live anywhere where the humidity hovers around 90 percent. That means the moist places in the house: garages, bathrooms, basements. Sometimes their presence can indicate of a leaky roof or pipe.

--- Do house centipedes have 100 legs?

No. An adult house centipede has 30. Only one group of centipedes, called the soil centipedes, actually have a hundred legs or more.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....018/09/25/the-house-

---+ For more information:

Visit the centipede page of the Natural History Museum, London:

http://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-scien....ce/our-work/origins-

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

How Kittens Go From Clueless to Cute

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o1xRlkNwQy8

This Adorable Sea Slug is a Sneaky Little Thief

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KLVfWKxtfow

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Origin of Everything: Why Do People Have Pets?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k2nW7_2VUMc

Hot Mess: What if Carbon Emissions Stopped Tomorrow?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A4kX9xKGeEw

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the Templeton Religion Trust and the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

Octopuses and cuttlefish are masters of underwater camouflage, blending in seamlessly against a rock or coral. But squid have to hide in the open ocean, mimicking the subtle interplay of light, water, and waves. How do they do it? (And it is NOT OCTOPI)

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

--- How do squid change color?

For an animal with such a humble name, market squid have a spectacularly hypnotic appearance. Streaks and waves of color flicker and radiate across their skin. Other creatures may posses the ability to change color, but squid and their relatives are without equal when it comes to controlling their appearance and new research may illuminate how they do it.

To control the color of their skin, cephalopods use tiny organs in their skin called chromatophores. Each tiny chromatophore is basically a sac filled with pigment. Minute muscles tug on the sac, spreading it wide and exposing the colored pigment to any light hitting the skin. When the muscles relax, the colored areas shrink back into tiny spots.

--- Why do squid change color?

Octopuses, cuttlefish and squid belong to a class of animals referred to as cephalopods. These animals, widely regarded as the most intelligent of the invertebrates, use their color change abilities for both camouflage and communication. Their ability to hide is critical to their survival since, with the exception of the nautiluses, these squishy and often delicious animals live without the protection of protective external shells.

But squid often live in the open ocean. How do you blend in when there's nothing -- except water -- to blend into? They do it by changing the way light bounces off their their skin -- actually adjust how iridescent their skin is using light reflecting cells called iridophores. They can mimic the way sunlight filters down from the surface. Hide in plain sight.

Iridophores make structural color, which means they reflect certain wavelengths of light because of their shape. Most familiar instances of structural color in nature (peacock feathers, mother of pearl) are constant–they may shimmer when you change your viewing angle, but they don't shift from pink to blue.

--- Read the article for this video on KQED Science:

http://ww2.kqed.org/science/20....15/09/08/youre-not-h

--- More great DEEP LOOK episodes:

What Gives the Morpho Butterfly Its Magnificent Blue?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=29Ts7CsJDpg

Nature's Mood Rings: How Chameleons Really Change Color

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kp9W-_W8rCM

Pygmy Seahorses: Masters of Camouflage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3CtGoqz3ww

--- Related videos from the PBS Digital Studios Network!

Cuttlefish: Tentacles In Disguise - It’s Okay to Be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lcwfTOg5rnc

Why Neuroscientists Love Kinky Sea Slugs - Gross Science

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QGHiyWjjhHY

The Psychology of Colour, Emotion and Online Shopping - YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=THTKv6dT8rU

--- More KQED SCIENCE:

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science: http://ww2.kqed.org/science

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #squid #octopus

Dragonflies might rule the skies, but their babies grow up underwater in a larva-eat-larva world. Luckily for them, they have a killer lip that snatches prey, Alien-style, at lightning speed.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

If adult dragonflies are known to be precise hunters, capable of turning on a dime and using their almost-360-degree vision to nab mosquitoes and flies in midair, their dragon-looking babies are even more fearsome.

Dragonflies and damselflies lay their eggs in water. After they hatch, their larvae, also known as nymphs, spend months or years underwater growing wings on their backs.

Without those versatile four wings that adults use to chase down prey, nymphs rely on a mouthpart they shoot out. It’s like a long, hinged arm that they keep folded under their head and it’s eerily similar to the snapping tongue-like protuberance the alien shoots out at Ripley in the sci-fi movie Aliens.

A nymph’s eyesight is almost as precise as an adult dragonfly’s and when they spot something they want to eat, they extrude this mouthpart, called a labium, to engulf, grab, or impale their next meal and draw it back to their mouth. Only dragonfly and damselfly nymphs have this special mouthpart.

“It’s like a built-in spear gun,” said Kathy Biggs, the author of guides to the dragonflies of California and the greater Southwest.

With their labium, nymphs can catch mosquito larvae, worms and even small fish and tadpoles.

“It’s obviously an adaptation to be a predator underwater, where it’s not easy to trap things,” said Dennis Paulson, a dragonfly biologist retired from the University of Puget Sound.

Also known among biologists as a “killer lip,” the labium comes in two versions. There’s the spork-shaped labium that scoops up prey, and a flat one with a pair of pincers on the end that can grab or impale aquatic insects.

-- How many years have dragonflies been around?

Dragonflies have been around for 320 million years, said Ed Jarzembowski, who studies fossil dragonflies at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology. That means they were here before the dinosaurs.

-- How big did dragonflies used to be?

Prehistoric dragonflies had a wingspan of 0.7 meters (almost 28 inches). That’s the wingspan of a small hawk today.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/09/12/a-baby-dra

---+ For more information:

This web site, run by Kathy and David Biggs, has photos and descriptions of California dragonflies and damselflies and information on building a pond to attract the insects to your backyard: http://bigsnest.members.sonic.net/Pond/dragons/

The book "A Dazzle of Dragonflies," by Forrest Mitchell and James Lasswell, has good information on dragonfly nymphs.

---+ More great Deep Look episodes:

Why Is The Very Hungry Caterpillar So Dang Hungry?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=el_lPd2oFV4

This Mushroom Starts Killing You Before You Even Realize It

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bl9aCH2QaQY&t=57s

Daddy Longlegs Risk Life ... and Especially Limb ... to Survive

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tjDmH8zhp6o

This Is Why Water Striders Make Terrible Lifeguards

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E2unnSK7WTE

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

PBS Eons: The Biggest Thing That Ever Flew

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=scAp-fncp64

PBS Infinite Series: A Breakthrough in Higher Dimensional Spheres

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ciM6wigZK0w

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate based in San Francisco, serves the people of Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial media. Home to one of the most listened-to public radio stations in the nation, one of the highest-rated public television services and an award-winning education program, KQED is also a leader and innovator in interactive media and technology, taking people of all ages on journeys of exploration – exposing them to new people, places and ideas.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #dragonflies #dragonflynymph

Termites cause billions of dollars in damage annually – but they need help to do it. So they carry tiny organisms around with them in their gut. Together, termites and microorganisms can turn the wood in your house into a palace of poop.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Termites such as dampwood termites use their cardboard-like poop pellets to build up their nests, turning a human house into a termite toilet. “They build their own houses out of their own feces,” said entomologist Michael Scharf, of Purdue University, in Indiana.

And while they’re using their poop as a building material, termites are also feeding on the wood. They’re one of the few animals that can extract nutrients from wood. But it turns out that they need help to do this.

A termite’s gut is host to a couple dozen species of protists, organisms that are neither animals, nor plants, nor fungi. Scientists have found that several of them help termites break down wood.

When some protists are eliminated from the termite’s gut, the insect can’t get any nutrition out of the wood. This is a weakness that biologists hope to exploit as a way to get rid of termites using biology rather than chemicals.

Louisiana State University entomologist Chinmay Tikhe is working to genetically engineer a bacterium found in the Formosan termite’s gut so that the bacterium will destroy the gut protists. The idea would be to sneak these killer bacteria into the termite colony on some sort of bait the termites would eat and carry back with them.

“It’s like a Trojan Horse,” said Tikhe, referring to the strategy used by the Greeks to sneak their troops into the city of Troy using a wooden horse that was the city’s emblem.

The bacteria would then kill the protists that help the termite derive nutrition from wood. The termites would eventually starve.

--- How do termites eat wood?

Termites gnaw on the wood. Then they mix it with enzymes that start to break it down. But they need help turning the cellulose in wood into nutrients. They get help from hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of species of microbes that live inside their guts. One bacterium, for example, combines nitrogen from the air and calories from the wood to make protein for the termites. A termite’s gut is also host to a couple dozen species of protists. In the termite’s hindgut, protists ferment the wood into a substance called acetate, which gives the termite energy.

--- How do termites get into our houses?

Termites can crawl up into a house from the soil through specialized tubes made of dirt and saliva, or winged adults can fly in, or both. This depends on the species and caste member involved.

--- What do termites eat in our houses?

Once they’re established in our houses, termites attack and feed on sources of cellulose, a major component of wood, says entomologist Vernard Lewis, of the University of California, Berkeley. This could include anything from structural wood and paneling, to furniture and cotton clothing. Termites also will eat dead or living trees, depending on the species.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....016/10/18/these-term

---+ For more information:

University of California Integrated Pest Management Program’s web page on termites:

http://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/PESTNOTES/pn7415.html

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

How Mosquitoes Use Six Needles to Suck Your Blood:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rD8SmacBUcU

For These Tiny Spiders, It’s Sing or Get Served:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y7qMqAgCqME

Where are the Ants Carrying All Those Leaves?:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-6oKJ5FGk24

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

It’s Okay To Be Smart: The Donald Trump Caterpillar and Nature’s Masters of Disguise

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VTUCTT6I1TU

Gross Science: Why Do Dogs Eat Poop?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z3pB-xZGM1U

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media. macro pest control

#deeplook

Check out America From Scratch: https://youtu.be/LVuEJ15J19s

A rattlesnake's rattle isn't like a maraca, with little bits shaking around inside. So how exactly does it make that sound?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Please support us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Watch America From Scratch: https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UClSZ6wHgU2h1W7eAG

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Rattlesnakes are ambush predators, relying on staying hidden to get close to their prey. They don’t sport the bright colors that some venomous snakes use as a warning to predators.

Fortunately, rattlesnakes have an unmistakable warning, a loud buzz made to startle any aggressor and hopefully avoid having to bite.

If you hear the rattlesnake’s rattle here’s what to do: First, stop moving! You want to figure out which direction the sound is coming from. Once you do, slowly back away.

If you do get bitten, immobilize the area and don't overly exert yourself. Immediately seek medical attention. You may need to be treated with antivenom.

DO NOT try to suck the venom out using your mouth or a suction device.

DO NOT try to capture the snake and stay clear of dead rattlesnakes, especially the head.

--- How do rattlesnakes make that buzzing sound?

The rattlesnake’s rattle is made up of loosely interlocking segments made of keratin, the same strong fibrous protein in your fingernails. Each segment is held in place by the one in front and behind it, but the individual segments can move a bit. When the snake shakes its tail, it sends undulating waves down the length of the rattle, and they click against each other. It happens so fast that all you hear is a buzz and all you see is a blur.

--- Why do rattlesnakes flick their tongue?

Like other snakes, rattlesnakes flick their tongues to gather odor particles suspended in liquid. The snake brings those scent molecules back to a special organ in the roof of their mouth called the vomeronasal organ or Jacobson's organ. The organ detects pheromones originating from prey and other snakes.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....945648/5-things-you-

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Stinging Scorpion vs. Pain-Defying Mouse | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w-K_YtWqMro&t=35s

---+ ?Congratulations ?to the following fans for coming up with the *best* new names for the Jacobson's organ in our community tab challenge:

Pigeon Fowl - "Noodle snoofer"

alex jackson - "Ye Ol' Factory"

Aberrant Artist - "Tiny boi sniffer whiffer"

vandent nguyen - "Smeller Dweller" and "Flicker Snicker"

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Allen, Aurora Mitchell, Beckie, Ben Espey, Bill Cass, Bluapex, Breanna Tarnawsky, Carl, Chris B Emrick, Chris Murphy, Cindy McGill, Companion Cube, Cory, Daisuke Goto, Daisy Trevino , Daniel Voisine, Daniel Weinstein, David Deshpande, Dean Skoglund, Edwin Rivas, Elizabeth Ann Ditz, Eric Carter, Geidi Rodriguez, Gerardo Alfaro, Ivan Alexander, Jane Orbuch, JanetFromAnotherPlanet, Jason Buberel, Jeanine Womble, Jeanne Sommer, Jiayang Li, Joao Ascensao, johanna reis, Johnnyonnyful, Joshua Murallon Robertson, Justin Bull, Kallie Moore, Karen Reynolds, Katherine Schick, Kendall Rasmussen, Kenia Villegas, Kristell Esquivel, KW, Kyle Fisher, Laurel Przybylski, Levi Cai, Mark Joshua Bernardo, Michael Mieczkowski, Michele Wong, Nathan Padilla, Nathan Wright, Nicolette Ray, Pamela Parker, PM Daeley, Ricardo Martinez, riceeater, Richard Shalumov, Rick Wong, Robert Amling, Robert Warner, Samuel Bean, Sayantan Dasgupta, Sean Tucker, Shelley Pearson Cranshaw, Shirley Washburn, Sonia Tanlimco, SueEllen McCann, Supernovabetty, Tea Torvinen, TierZoo, Titania Juang, Two Box Fish, WhatzGames, Willy Nursalim, Yvan Mostaza,

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

When predators attack, daddy longlegs deliberately release their limbs to escape. They can drop up to three and still get by just fine.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

We all know it’s not nice to pull the legs off of bugs.

Daddy longlegs don’t wait for that to happen. These arachnids, related to spiders, drop them deliberately. A gentle pinch is enough to trigger an internal system that discharges the leg. Whether it hurts is up for debate, but most scientists think not, given the automatic nature of the defense mechanism.

It’s called autotomy, the voluntary release of a body part.

Two of their appendages have evolved into feelers, which leaves the other six legs for locomotion. Daddy longlegs share this trait with insects, and have what scientists call the “alternate tripod gate,” where three legs touch the ground at any given point.

That elegant stride is initially hard-hit by the loss of a leg. In the daddy longlegs’ case, the lost leg doesn’t grow back.

But they persevere: A daddy longlegs that is one, two, or even three legs short can recover a surprising degree of mobility by learning to walk differently. And given time, the daddy longlegs can regain much of its initial mobility on fewer legs.

Once these adaptations are better understood, they may have applications in the fields of robotics and prosthetic design.

--- Are daddy longlegs a type of spider?

No, though they are arachnids, as spiders are. Daddy longlegs are more closely related to scorpions.

--- How can I tell a daddy longlegs from a spider?

Daddy longlegs have one body segment (like a pea), while spiders have two (like a peanut). Also, you won’t find a daddy longlegs in a web, since they don’t make silk.

--- Can a daddy longlegs bite can kill you?

Daddy longlegs are not venomous. And despite what you’ve heard about their mouths being too small, they could bite you, but they prefer fruit.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/08/22/daddy-long

---+ For more information:

Visit the Elias Lab at UC Berkeley:

https://nature.berkeley.edu/eliaslab/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Stinging Scorpion vs. Pain-Defying Mouse | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w-K_YtWqMro

For These Tiny Spiders, It's Sing or Get Served | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y7qMqAgCqME

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Gross Science: What Happens When You Get Rabies?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eiUUpF1UPJc

Physics Girl: Mantis Shrimp Punch at 40,000 fps! - Cavitation Physics

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m78_sOEadC8

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate based in San Francisco, serves the people of Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial media. Home to one of the most listened-to public radio station in the nation, one of the highest-rated public television services and an award-winning education program, KQED is also a leader and innovator in interactive media and technology, taking people of all ages on journeys of exploration — exposing them to new people, places and ideas.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #daddylonglegs #harvestman

Join Deep Look on Patreon NOW!

https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

They may be dressed in black, but crow funerals aren't the solemn events that we hold for our dead. These birds cause a ruckus around their fallen friend. Are they just scared, or is there something deeper going on?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

It’s a common site in many parks and backyards: Crows squawking. But groups of the noisy black birds may not just be raising a fuss, scientists say. They may be holding a funeral.

Kaeli Swift, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Washington’s Avian Conservation Lab in Seattle, is studying how crows learn about danger from each other and how they respond to seeing one of their own who has died.

Unlike the majority of animals, crows react strongly to seeing a fellow member of their species has died, mobbing together and raising a ruckus.

Only a few animals like whales, elephants and some primates, have such strong reactions.

To study exactly what may be going on on, Swift developed an experiment that involved exposing local crows in Seattle neighborhoods to a dead taxidermied crow in order to study their reaction.

“It’s really incredible,” she said. “They’re all around in the trees just staring at you and screaming at you.”

Swift calls these events ‘crow funerals’ and they are the focus of her research.

--- What do crows eat?

Crows are omnivores so they’ll eat just about anything. In the wild they eat insects, carrion, eggs seeds and fruit. Crows that live around humans eat garbage.

--- What’s the difference between crows and ravens?

American crows and common ravens may look similar but ravens are larger with a more robust beak. When in flight, crow tail feathers are approximately the same length. Raven tail feathers spread out and look like a fan.

Ravens also tend to emit a croaking sound compared to the caw of a crow. Ravens also tend to travel in pairs while crows tend to flock together in larger groups. Raven will sometimes prey on crows.

--- Why do crows chase hawks?

Crows, like animals whose young are preyed upon, mob together and harass dangerous predators like hawks in order to exclude them from an area and protect their offspring. Mobbing also teaches new generations of crows to identify predators.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....923458/youve-heard-o

---+ For more information:

Kaeli Swift’s Corvid Research website

https://corvidresearch.blog/

University of Washington Avian Conservation Laboratory

http://sefs.washington.edu/research.acl/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Why Do Tumbleweeds Tumble? | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dATZsuPdOnM

Upside-Down Catfish Doesn't Care What You Think | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eurCBOJMrsE

Take Two Leeches and Call Me in the Morning | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O-0SFWPLaII

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

Why Climate Change is Unjust | Hot Mess

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q5KjpYK12_c

Is Breakfast the Most Important Meal? | Origin Of Everything

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AxIOGqHQqZM

How the Squid Lost Its Shell | PBS Eons

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S4vxoP-IF2M

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the Templeton Religion Trust and the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

What if you had to grow 20 pounds of bone on your forehead each year just to find a mate? In a bloody, itchy process, males of the deer family grow a new set of antlers every year, use them to fend off the competition, and lose their impressive crowns when breeding season ends.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* WE’RE TAKING A BREAK FOR THE HOLIDAYS. WATCH OUR NEXT EPISODE ON JAN. 17, 2017. *

Antlers are bones that grow right out of an animal’s head. It all starts with little knobs called pedicles. Reindeer, elk, and their relatives in the cervid family, like moose and deer, are born with them. But in most species pedicles only sprout antlers in males, because antlers require testosterone.

The little antlers of a young tule elk, or a reindeer, are called spikes. Every year, a male grows a slightly larger set of antlers, until he becomes a “senior” and the antlers start to shrink.

While it’s growing, the bone is hidden by a fuzzy layer of skin and fur called velvet that carries blood rich in calcium and phosphorous to build up the bone inside.

When the antlers get hard, the blood stops flowing and the velvet cracks. It gets itchy and males scratch like crazy to get it off. From underneath emerges a clean, smooth antler.

Males use their antlers during the mating season as a warning to other males to stay away from females, or to woo the females. When their warnings aren’t heeded, they use them to fight the competition.

Once the mating season is over and the male no longer needs its antlers, the testosterone in its body drops and the antlers fall off. A new set starts growing almost right away.

--- What are antlers made of?

Antlers are made of bone.

--- What is antler velvet?

Velvet is the skin that covers a developing antler.

--- What animals have antlers?

Male members of the cervid, or deer, family grow antlers. The only species of deer in which females also grow antlers are reindeer.

--- Are antlers horns?

No. Horns, which are made of keratin (the same material our nails are made from), stay on an animal its entire life. Antlers fall off and grow back again each year.

---+ Read an article on KQED Science about how neuroscientists are investigating the potential of the nerves in antler velvet to return mobility to damaged human limbs, and perhaps one day even help paralyzed people:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....016/12/06/rudolphs-a

---+ For more information on tule elk

https://www.nps.gov/pore/learn/nature/tule_elk.htm

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

The Sex Lives of Christmas Trees

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xEji9I4Tcjo

Watch These Frustrated Squirrels Go Nuts!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZUjQtJGaSpk

This Mushroom Starts Killing You Before You Even Realize It

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bl9aCH2QaQY

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

The REAL Rudolph Has Bloody Antlers and Super Vision - Gross Science

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gB6ND8nXgjA

Global Weirding with Katharine Hayhoe: Texans don't care about climate change, right?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P_r_6D2LXVs&list=PL1mtdjDVOoOqJzeaJAV15Tq0tZ1vKj7ZV&index=25

It’s Okay To Be Smart: Why Don’t Woodpeckers Get Concussions?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bqBxbMWd8O0

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Mammalian moms, you're not alone! A female tsetse fly pushes out a single squiggly larva almost as big as herself, which she nourished with her own milk.

Please join our community on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

---

Mammalian moms aren’t the only ones to deliver babies and feed them milk. Tsetse flies, the insects best known for transmitting sleeping sickness, do it too.

A researcher at the University of California, Davis is trying to understand in detail the unusual way in which these flies reproduce in order to find new ways to combat the disease, which has a crippling effect on a huge swath of Africa.

When it’s time to give birth, a female tsetse fly takes less than a minute to push out a squiggly yellowish larva almost as big as itself. The first time he watched a larva emerge from its mother, UC Davis medical entomologist Geoff Attardo was reminded of a clown car.

“There’s too much coming out of it to be able to fit inside,” he recalled thinking. “The fact that they can do it eight times in their lifetime is kind of amazing to me.”

Tsetse flies live four to five months and deliver those eight offspring one at a time. While the larva is growing inside them, they feed it milk. This reproductive strategy is extremely rare in the insect world, where survival usually depends on laying hundreds or thousands of eggs.

--- What is sleeping sickness?

Tsetse flies, which are only found in Africa, feed exclusively on the blood of humans and other domestic and wild animals. As they feed, they can transmit microscopic parasites called trypanosomes, which cause sleeping sickness in humans and a version of the disease known as nagana in cattle and other livestock. Sleeping sickness is also known as human African trypanosomiasis.

--- What are the symptoms of sleeping sickness?

The disease starts with fatigue, anemia and headaches. It is treatable with medication, but if trypanosomes invade the central nervous system they can cause sleep disruptions and hallucinations and eventually make patients fall into a coma and die.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....956004/a-tsetse-fly-

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

“Parasites Are Dynamite” Deep Look playlist:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C2Jw5ib-s_I&list=PLdKlciEDdCQACmrtvWX7hr7X7Zv8F4nEi

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to these fans on our YouTube community tab who correctly identified the function of the black protuberances on a tsetse fly larva - polypneustic lobes:

Jeffrey Kuo

Lizzie Zelaya

Art3mis YT

Garen Reynolds

Torterra Grey8

Despite looking like a head, they’re actually located at the back of the larva, which used them to breathe while growing inside its mother. The larva continues to breathe through the lobes as it develops underground.

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Alice Kwok

Allen

Amber Miller

Aurora

Aurora Mitchell

Bethany

Bill Cass

Blanca Vides

Burt Humburg

Caitlin McDonough

Cameron

Carlos Carrasco

Chris B Emrick

Chris Murphy

Cindy McGill

Companion Cube

Daisuke Goto

Daniel Weinstein

David Deshpande

Dean Skoglund

Edwin Rivas

Egg-Roll

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

Geidi Rodriguez

Gerardo Alfaro

Guillaume Morin

Jane Orbuch

Joao Ascensao

johanna reis

Johnnyonnyful

Josh Kuroda

Joshua Murallon Robertson

Justin Bull

Kallie Moore

Karen Reynolds

Katherine Schick

Kathleen R Jaroma

Kendall Rasmussen

Kristy Freeman

KW

Kyle Fisher

Laura Sanborn

Laurel Przybylski

Leonhardt Wille

Levi Cai

Louis O'Neill

luna

Mary Truland

monoirre

Natalie Banach

Nathan Wright

Nicolette Ray

Noreen Herrington

Osbaldo Olvera

Pamela Parker

Richard Shalumov

Rick Wong

Robert Amling

Robert Warner

Roberta K Wright

Sarah Khalida Mohamad

Sayantan Dasgupta

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

Silvan Wendland

Sonia Tanlimco

SueEllen McCann

Supernovabetty

Syniurge

Tea Torvinen

TierZoo

Titania Juang

Trae Wright

Two Box Fish

WhatzGames

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

#tsetsefly #sleepingsickness #deeplook

Support Deep Look on Patreon!! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

The notorious death cap mushroom causes poisonings and deaths around the world. If you were to eat these unassuming greenish mushrooms by mistake, you wouldn’t know your liver is in trouble until several hours later. The death cap has been spreading across California. Can scientists find a way to stop it?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Find out more on KQED Science:

http://ww2.kqed.org/science/20....16/02/23/this-mushro

Where do death cap mushrooms grow?

In California, they grow mainly under coast live oaks. They have also been found under pines, and in Yosemite Valley under black oaks.

Why do death caps grow under trees?

As many fungi do, death cap mushrooms live off of trees, in what’s called a mycorrhizal relationship. They send filaments deep down to the trees’ roots, where they attach to the very thin root tips. The fungi absorb sugars from the trees and give them nutrients in exchange.

Where do California’s death cap mushrooms come from?

Biologist Anne Pringle, at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, has done research that shows that death caps likely snuck into California from Europe attached to the roots of imported plants, as early as 1938.

How deadly are death cap mushrooms?

Between 2010 and 2015, five people died in California and 57 became sick after eating the unassuming greenish mushrooms, according to the California Poison Control System. One mushroom cap is enough to kill a human being, and they’re also poisonous to dogs. Death caps are believed to be the number one cause of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide.

What happens if you eat a death cap mushroom?

A toxin in the mushroom destroys your liver cells. Dr. Kent Olson, co-medical director of the San Francisco Division of the California Poison Control System, said that for the first six to 12 hours after they eat the mushroom, victims of the death cap feel fine. During that time, a toxin in the mushroom is quietly injuring their liver cells. Patients then develop severe abdominal pain, diarrhea and vomiting. “They can become very rapidly dehydrated from the fluid losses,” said Olson. Dehydration can cause kidney failure, which compounds the damage to the liver. For the most severe cases, the only way to save the patient is a liver transplant.

For more information on the death cap:

Bay Area Mycological Society’s page with photos: http://bayareamushrooms.org/mu....shroommonth/amanita_

Rod Tulloss’ detailed description: http://www.amanitaceae.org/?Amanita%20phalloides

More great Deep Look episodes:

What Happens When You Zap Coral With The World's Most Powerful X-ray Laser?

https://youtu.be/aXmCU6IYnsA

These 'Resurrection Plants' Spring Back to Life in Seconds

https://youtu.be/eoFGKlZMo2g

See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay to Be Smart: Your Salad Is Trying To Kill You

https://youtu.be/8Ofgj2KDbfk

It's Okay to Be Smart: The Oldest Living Things In The World

https://youtu.be/jgspUYDwnzQ

For more content from your local PBS and NPR affiliate:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #mushroom #deathcap

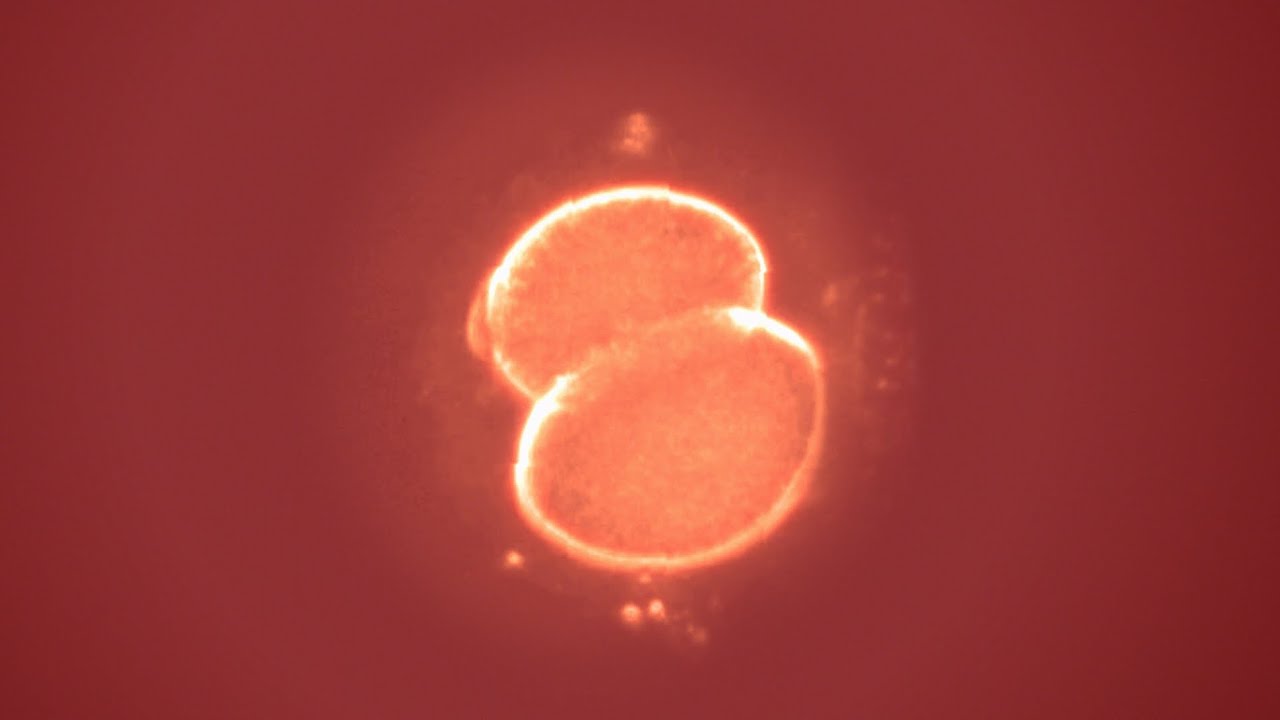

Every one of us started out as an embryo, but only a few early embryos – about one in three – grow into a baby. Researchers are unlocking the mysteries of our embryonic clock and helping patients who are struggling to get pregnant.

SUBSCRIBE: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

It's an all-out brawl for prime beach real estate! These Caribbean crabs will tear each other limb from limb to get the best burrow. Luckily, they molt and regrow lost legs in a matter of weeks, and live to fight another day.

You can learn more about CuriosityStream at https://curiositystream.com/deeplook

Help Deep Look grow by supporting us on Patreon!!

https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

PBS Digital Studios Mega-playlist:

https://www.youtube.com/playli....st?list=PL1mtdjDVOoO

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

On the sand-dune beaches where they live, male blackback land crabs do constant battle over territory. The stakes are high: If one of these baby-faced crabs secures a winning spot, he can invite a mate into his den, six or seven feet beneath the surface.

With all this roughhousing, more than feelings get hurt. The male crabs inevitably lose limbs and damage their shells in constant dust-ups. Luckily, like many other arthropods, a group that includes insects and spiders, these crabs can release a leg or claw voluntarily if threatened. It’s not unusual to see animals in the field missing two or three walking legs.

The limbs regrow at the next molt, which is typically once a year for an adult. When a molt cycle begins, tiny limb buds form where a leg or a claw has been lost. Over the next six to eight weeks, the buds enlarge while the crab reabsorbs calcium from its old shell and secretes a new, paper-thin one underneath.

In the last hour of the cycle, the crab gulps air to create enough internal pressure to pop open the top of its shell, called the carapace. As the crab pushes it way out, the same internal pressure helps uncoil the new legs. The replacement shell thickens and hardens, and the crab eats the old shell.

--- Are blackback land crabs edible?

Yes, but they’re not as popular as the major food species like Dungeness and King crab.

--- Where do blackback land crabs live?

They live throughout the Caribbean islands.

--- Does it hurt when they lose legs?

Hard to say, but they do have an internal mechanism for releasing limbs cleanly that prevents loss of blood.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....933532/whack-jab-cra

---+ For more information:

The Crab Lab at Colorado State University:

https://rydberg.biology.colostate.edu/mykleslab/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Want a Whole New Body? Ask This Flatworm How

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m12xsf5g3Bo

Daddy Longlegs Risk Life ... and Especially Limb ... to Survive

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tjDmH8zhp6o

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Origin of Everything: The Origin of Gender

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5e12ZojkYrU

Hot Mess: Coral Reefs Are Dying. But They Don’t Have To.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MUAsFZuFQvQ

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the Templeton Religion Trust, the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

---+ Shoutout!

Congratulations to ?Jen Wiley?, who was the first to correctly ID the species of crab in our episode over at the Deep Look Community Tab:

https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UC-3SbfTPJsL8fJAPK

#deeplook #pbsds #crab

A deadly fungus is attacking frogs’ skin and wiping out hundreds of species worldwide. Can anyone help California's remaining mountain yellow-legged frogs? In a last-ditch effort, scientists are trying something new: build defenses against the fungus through a kind of frog “vaccine.”

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Chytrid fungus has decimated some 200 amphibian species around the world, among them the mountain yellow-legged frogs of California’s Sierra Nevada mountain range.

Frogs need healthy skin to survive. They breathe and drink water through it, and absorb the sodium and potassium their hearts need to work.

In the late 1970s, chytrid fungus started getting into mountain yellow-legged frogs through their skin, moving through the water in their alpine lakes, or passed on by other frogs. The fungus destroys frogs’ skin to the point where they can no longer absorb sodium and potassium. Eventually, they die.

At the University of California, Santa Barbara, biologists Cherie Briggs and Mary Toothman did an experiment to see if they could save mountain yellow-legged frogs by immunizing them against chytrid fungus.

They grew some frogs from eggs. Then they infected them with chytrid fungus. The frogs got sick. Their skin sloughed off, as happens typically to infected frogs. But before the fungus could kill the frogs, the researchers treated them with a liquid antifungal that stopped the disease.

When the frogs were nice and healthy again, researchers re-infected them with chytrid fungus. They found that all 20 frogs they had immunized survived. Now the San Francisco and Oakland zoos are replicating the experiment and returning dozens of mountain-yellow legged frogs to the Sierra Nevada’s alpine lakes.

--- How does chytrid fungus kill frogs?

Spores of chytrid fungus burrow down into frogs’ skin, which gets irritated. They run out of energy. Sick frogs’ legs lock in the straight position when they try to hop. As they get sicker, their skin sloughs off in translucent sheets. The frogs can no longer absorb sodium and potassium their hearts needs to function. “It takes 2-3 weeks for a yellow-legged frog to die from chytridiomycosis,” said mountain yellow-legged frog expert Vance Vredenburg , of San Francisco State University. “Eventually they die from a heart attack.”

--- How does chytrid fungus spread?

Fungus spores, which have a little tail called a flagellum, swim through the water and attack a frog’s skin. The fungus can also get passed on from amphibian to amphibian.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....016/09/06/can-a-new-

---+ For more information:

AmphibiaWeb

http://www.amphibiaweb.org/chy....trid/chytridiomycosi

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

These Crazy Cute Baby Turtles Want Their Lake Back

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YTYFdpNpkMY

Newt Sex: Buff Males! Writhing Females! Cannibalism!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5m37QR_4XNY

Sticky. Stretchy. Waterproof. The Amazing Underwater Tape of the Caddisfly

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z3BHrzDHoYo

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

It’s Okay To Be Smart: Do Plants Think?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zm6zfHzvqX4

Gross Science: Why Get Your Tetanus Shot?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O4jrqj5Dr8s

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Thanks to The Great Courses Plus for sponsoring this episode of Deep Look. Try a 30 day trial of The Great Course Plus at http://ow.ly/7QYH309wSOL. If you liked this episode, you might be interested in their course “Major Transitions in Evolution”.

POW! BAM! Fruit flies battling like martial arts masters are helping scientists map brain circuits. This research could shed light on human aggression and depression.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Neuroscientist Eric Hoopfer likes to watch animals fight. But these aren’t the kind of fights that could get him arrested – no roosters or pit bulls are involved.

Hoopfer watches fruit flies.

The tiny insects are the size of a pinhead, with big red eyes and iridescent wings. You’ve probably only seen them flying around an overripe piece of fruit.

At the California Institute of Technology, in Pasadena, Hoopfer places pairs of male fruit flies in tiny glass chambers. When they start fighting, they look like martial arts practitioners: They stand face to face and tip each other over; they lunge, roll around and even toss each other, sumo-wrestler style.

But this isn’t about entertainment. Hoopfer is trying to understand how the brain works.

When the aggressive fruit flies at Caltech fight, Hoopfer and his colleagues monitor what parts of their brains the flies are using. The researchers can see clusters of neurons lighting up. In the future, they hope this can help our understanding of conditions that tap into human emotional states, like depression or addiction.

“Flies when they fight, they fight at different intensities. And once they start fighting they continue fighting for a while; this state persists. These are all things that are similar to (human) emotional states,” said Hoopfer. “For example, there’s this scale of emotions where you can be a little bit annoyed and that can scale up to being very angry. If somebody cuts you off in traffic you might get angry and that lasts for a little while. So your emotion lasts longer than the initial stimulus.”

Circuits in our brains that make us stay mad, for example, could hold the key to developing better treatments for mental illness.

“All these neuro-psychiatric disorders, like depression, addiction, schizophrenia, the drugs that we have to treat them, we don’t really understand exactly how they are acting at the level of circuits in the brain,” said Hoopfer. “They help in some cases the symptoms that you want to treat. But they also cause a lot of side effects. So what we’d ideally like are drugs that can act on the specific neurons and circuits in the brain that are responsible for depression and for the symptoms of depression that we want to treat, and not ones that control other things.”

--- What do fruit flies eat?

In the lab, researchers feed fruit flies yeast and apple juice.

--- How do I get rid of fruit flies in my house?

Fruit flies are attracted to ripe fruit and vegetables.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/03/28/these-figh

---+ For more information:

The David Anderson Lab at Caltech:

https://davidandersonlab.caltech.edu/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

How Mosquitoes Use Six Needles to Suck Your Blood

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rD8SmacBUcU

Meet the Dust Mites, Tiny Roommates That Feast On Your Skin

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ACrLMtPyRM0

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It’s Okay To Be Smart: Why Your Brain Is In Your Head

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdNE4WygyAk

BrainCraft: Can You Solve This Dilemma?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9xHKxrc0PHg

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience