Top Vídeos

Brown pelicans hit the water at breakneck speed when they catch fish. Performing such dangerous plunges requires technique, equipment, and 30 million years of practice.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

California’s brown pelicans are one of two pelican species (once considered the same) that plunge from the air to hunt. The rest, like the white pelican, bob for fish at the water’s surface.

The shape of its bill is essential to the birds' survival in these dives, reducing “hydrodynamic drag” — buckling forces, caused by the change from air to water — to almost zero. It’s something like the difference between slapping the water with your palm and chopping it, karate-style.

And while all birds have light, air-filled bones, pelican skeletons take it to an extreme. As they dive, they inflate special air sacs around their neck and belly, cushioning their impact and allowing them to float.

Even their celebrated pouches play a role. An old limerick quips, “A remarkable bird is a pelican / Its beak can hold more than its belly can…” That beak is more than just a fishing net. It’s also a parachute that pops open underwater, helping to slow the bird down.

Behind the pelican’s remarkable resilience (and beaks) lies 30 million years of evolutionary stasis, meaning they haven’t changed much over time.

--- What do pelicans eat?

Pelicans eat small fish like anchovies, sardines, and smelt.

--- How long to pelicans live?

Pelicans live 15-25 years in the wild.

--- How big are pelicans?

Brown pelicans are small for pelicans, but still big for birds, with a 6-8 foot wingspan. Their average weight is 3.5 kg.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/04/25/volunteer-

---+ For more information:

U.S. Fish and Wildlife brown pelican page

https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp0/prof....ile/speciesProfile?s

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

The Fantastic Fur of Sea Otters

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zxqg_um1TXI

How Do Sharks and Rays Use Electricity to Find Hidden Prey?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JDPFR6n8tAQ

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Physics Girl: Why Outlets Spark When Unplugging

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g1Ld8D2bnJM

Gross Science: Everything You Didn’t Want to Know About Snot

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=shEPwQPQG4I

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Sea otters aren't just cute -- they're a vivid example of life on the edge. Unlike whales and other ocean mammals, sea otters have no blubber. Yet they're still able to keep warm in the frigid Pacific waters. The secret to their survival? A fur coat like no other.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Find out more about the sea otter's fantastic fur: http://goo.gl/kdPvWV

Check out UC Santa Cruz's Marine Mammal Physiology Project: http://goo.gl/ntwUHp

Find out what Monterey Bay Aquarium is doing to save Southen sea otters: http://goo.gl/bbnxm0

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

Happy #WorldOtterDay !

#deeplook

Support Deep Look on Patreon!!

https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Why can't you just flick a tick? Because it attaches to you with a mouth covered in hooks, while it fattens up on your blood. For days. But don't worry – there *is* a way to pull it out.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Spring is here. Unfortunately for hikers and picnickers out enjoying the weather, the new season is prime time for ticks, which can transmit bacteria that cause Lyme disease.

How they latch on – and stay on – is a feat of engineering that scientists have been piecing together. Once you know how a tick’s mouth works, you understand why it’s impossible to simply flick a tick.

The key to their success is a menacing mouth covered in hooks that they use to get under the surface of our skin and attach themselves for several days while they fatten up on our blood.

“Ticks have a lovely, evolved mouth part for doing exactly what they need to do, which is extended feeding,” said Kerry Padgett, supervising public health biologist at the California Department of Public Health in Richmond. “They're not like a mosquito that can just put their mouth parts in and out nicely, like a hypodermic needle.”

Instead, a tick digs in using two sets of hooks. Each set looks like a hand with three hooked fingers. The hooks dig in and wriggle into the skin. Then these “hands” bend in unison to perform approximately half-a-dozen breaststrokes that pull skin out of the way so the tick can push in a long stubby part called the hypostome.

“It’s almost like swimming into the skin,” said Dania Richter, a biologist at the Technische Universität Braunschweig in Germany, who has studied the mechanism closely. “By bending the hooks it’s engaging the skin. It’s pulling the skin when it retracts.”

The bottom of their long hypostome is also covered in rows of hooks that give it the look of a chainsaw. Those hooks act like mini-harpoons, anchoring the tick to us for the long haul.

“They’re teeth that are backwards facing, similar to one of those gates you would drive over but you're not allowed to back up or else you'd puncture your tires,” said Padgett.

--- How to remove a tick.

Kerry Padgett, at the California Department of Public Health, recommends grabbing the tick close to the skin using a pair of fine tweezers and simply pulling straight up.

“No twisting or jerking,” she said. “Use a smooth motion pulling up.”

Padgett warned against using other strategies.

“Don't use Vaseline or try to burn the tick or use a cotton swab soaked in soft soap or any of these other techniques that might take a little longer or might not work at all,” she said. “You really want to remove the tick as soon as possible.”

--- What happens if the mouth of a tick breaks off in your skin?

Don’t worry if the tick’s mouth parts stay behind when you pull.

“The mouth parts are not going to transmit disease to people,” said Padgett.

If the mouth stayed behind in your skin, it will eventually work its way out, sort of like a splinter does, she said. Clean the bite area with soap and water and apply antibiotic ointment.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science: https://www.kqed.org/science/1....920972/how-ticks-dig

---+ For more information:

Centers for Disease Control information on Lyme disease:

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/

Mosquito & Vector Control District for San Mateo County, California:

https://www.smcmvcd.org/ticks

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

How Mosquitoes Use Six Needles to Suck Your Blood

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rD8SmacBUcU

So … Sometimes Fireflies Eat Other Fireflies

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oWdCMFvgFbo

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Above the Noise: Are Energy Drinks Really that Bad?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5l0cjsZS-eM

It’s Okay To Be Smart: Inside an ICE CAVE! - Nature's Most Beautiful Blue

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P7LKm9jtm8I

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #ticks #tickbite

When attacked, this beetle sets off a rapid chemical reaction inside its body, sending predators scrambling. This amazing chemical defense has some people scratching their heads: How could such a complex system evolve gradually—without killing the beetle too?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

The bombardier beetle, named for soldiers who once operated artillery cannons, has a surprising secret to use against potential predators.

When attacked, the beetle mixes a cocktail of compounds inside its body that produces a fast-moving chemical reaction. The reaction heats the mix to the boiling point, then propels it through a narrow abdominal opening with powerful force. By turning the end of its abdomen on an assailant, the beetle can even aim the spray.

The formidable liquid, composed of three main ingredients, both burns and stings the attacker. It can kill a small adversary, such as an ant, and send larger foes, like spiders, frogs, and birds, fleeing in confusion.

How do bombardier beetles defend themselves?

They manufacture and combine three reactive substances inside their bodies. The chemical reaction is exothermic, meaning it heats the combination to the boiling point, producing a hot, stinging spray, which the beetle can point at an enemy.

What does a bombardier beetle spray?

It’s a combination of hydroquinone and hydrogen peroxide (like what you can buy in the store). The reaction between these two is catalyzed by an enzyme, produced by glands in the beetle, which is the spark that makes the reaction so explosive.

Why is it called a bombardier beetle?

“Bombardier” is an old French word for a solider who operates artillery.

Read the entire article on KQED Science:

http://ww2.kqed.org/science/20....16/03/22/kaboom-this

--- More great DEEP LOOK episodes:

Halloween Special: Watch Flesh-Eating Beetles Strip Bodies to the Bone

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Np0hJGKrIWg

What Happens When You Put a Hummingbird in a Wind Tunnel?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JyqY64ovjfY

Nature's Scuba Divers: How Beetles Breathe Underwater

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T-RtG5Z-9jQ

--- Super videos from the PBS Digital Studios Network!

Nature's Most Amazing Animal Superpowers | It's Okay to Be Smart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e69yaWDkVGs

Why Don’t These Cicadas Have Butts? | Gross Science

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IDBkj3DjNSM

--- For more content from your local PBS and NPR affiliate:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Check out America From Scratch: https://youtu.be/LVuEJ15J19s

A rattlesnake's rattle isn't like a maraca, with little bits shaking around inside. So how exactly does it make that sound?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Please support us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Watch America From Scratch: https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UClSZ6wHgU2h1W7eAG

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Rattlesnakes are ambush predators, relying on staying hidden to get close to their prey. They don’t sport the bright colors that some venomous snakes use as a warning to predators.

Fortunately, rattlesnakes have an unmistakable warning, a loud buzz made to startle any aggressor and hopefully avoid having to bite.

If you hear the rattlesnake’s rattle here’s what to do: First, stop moving! You want to figure out which direction the sound is coming from. Once you do, slowly back away.

If you do get bitten, immobilize the area and don't overly exert yourself. Immediately seek medical attention. You may need to be treated with antivenom.

DO NOT try to suck the venom out using your mouth or a suction device.

DO NOT try to capture the snake and stay clear of dead rattlesnakes, especially the head.

--- How do rattlesnakes make that buzzing sound?

The rattlesnake’s rattle is made up of loosely interlocking segments made of keratin, the same strong fibrous protein in your fingernails. Each segment is held in place by the one in front and behind it, but the individual segments can move a bit. When the snake shakes its tail, it sends undulating waves down the length of the rattle, and they click against each other. It happens so fast that all you hear is a buzz and all you see is a blur.

--- Why do rattlesnakes flick their tongue?

Like other snakes, rattlesnakes flick their tongues to gather odor particles suspended in liquid. The snake brings those scent molecules back to a special organ in the roof of their mouth called the vomeronasal organ or Jacobson's organ. The organ detects pheromones originating from prey and other snakes.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....945648/5-things-you-

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Stinging Scorpion vs. Pain-Defying Mouse | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w-K_YtWqMro&t=35s

---+ ?Congratulations ?to the following fans for coming up with the *best* new names for the Jacobson's organ in our community tab challenge:

Pigeon Fowl - "Noodle snoofer"

alex jackson - "Ye Ol' Factory"

Aberrant Artist - "Tiny boi sniffer whiffer"

vandent nguyen - "Smeller Dweller" and "Flicker Snicker"

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Allen, Aurora Mitchell, Beckie, Ben Espey, Bill Cass, Bluapex, Breanna Tarnawsky, Carl, Chris B Emrick, Chris Murphy, Cindy McGill, Companion Cube, Cory, Daisuke Goto, Daisy Trevino , Daniel Voisine, Daniel Weinstein, David Deshpande, Dean Skoglund, Edwin Rivas, Elizabeth Ann Ditz, Eric Carter, Geidi Rodriguez, Gerardo Alfaro, Ivan Alexander, Jane Orbuch, JanetFromAnotherPlanet, Jason Buberel, Jeanine Womble, Jeanne Sommer, Jiayang Li, Joao Ascensao, johanna reis, Johnnyonnyful, Joshua Murallon Robertson, Justin Bull, Kallie Moore, Karen Reynolds, Katherine Schick, Kendall Rasmussen, Kenia Villegas, Kristell Esquivel, KW, Kyle Fisher, Laurel Przybylski, Levi Cai, Mark Joshua Bernardo, Michael Mieczkowski, Michele Wong, Nathan Padilla, Nathan Wright, Nicolette Ray, Pamela Parker, PM Daeley, Ricardo Martinez, riceeater, Richard Shalumov, Rick Wong, Robert Amling, Robert Warner, Samuel Bean, Sayantan Dasgupta, Sean Tucker, Shelley Pearson Cranshaw, Shirley Washburn, Sonia Tanlimco, SueEllen McCann, Supernovabetty, Tea Torvinen, TierZoo, Titania Juang, Two Box Fish, WhatzGames, Willy Nursalim, Yvan Mostaza,

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

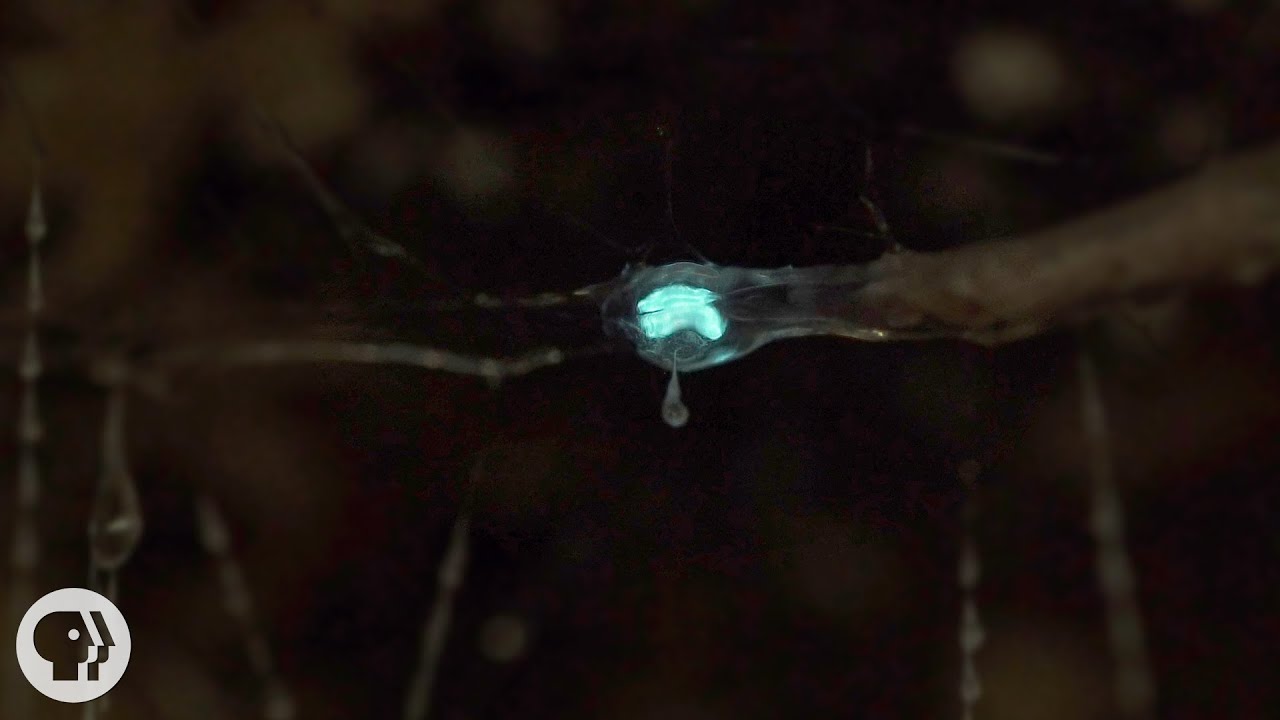

The glow worm colonies of New Zealand's Waitomo Caves imitate stars to confuse flying insects, then trap them in sticky snares and eat them alive.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is science up close - really, really close. An ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Like fireflies, the spectacular worms of New Zealand’s Waitomo Caves glow by breaking down a light-emitting protein. But unlike the yellow mating flashes of fireflies, the glow worms’ steady blue light has a more insidious purpose: it’s bait.

The strategy is simple. Many of the glow worms’ prey are insects, including moths, that navigate by starlight. With imposter stars all around, the insects become disoriented and fly into a waiting snare. Once the victim has exhausted itself trying to get free, the glow worm reels in the catch.

The prey is typically still alive when it arrives at the glow worm’s mouth, which has teeth sharp enough to bore through insect exoskeletons.

Glow worms live in colonies, and researchers have noticed that individual worms seem to sync their lights to the members of their colony, brightening and dimming on a 24-hour cycle. There can be several colonies of glow worms in a cave, and studies have shown that different colonies are on different cycles, taking turns at peak illumination, when they’re most attractive to prey.

Not surprisingly, the worms glow brighter when they’re hungry.

--- How do glow worms glow?

Their light is the result of a chemical reaction. The worms break down a protein called luciferin using an enzyme, luciferase, in a specialized section of their digestive tract. The glow shines through their translucent skin.

--- Why do glow worms live in caves?

The glow worms need to be in a dark environment where their light can be seen. Caves also shelter them from the wind, which can tangle their dangling snares.

--- Where can I see glow worms?

The Waitomo Caves are on New Zealand’s North Island. Other New Zealand glow worm sites include the Te Anau caves, Lake Rotoiti, Paparoa National Park, and Waipu. A related species inhabits similar caves in eastern Australia.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....016/06/28/these-carn

---+ For more information:

Discover Waitomo: http://www.waitomo.com/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Winter is Coming For These Argentine Ant Invaders

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=boyzWeHdtiI

The Bombardier Beetle And Its Crazy Chemical Cannon

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BWwgLS5tK80

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay to Be Smart: Are You Smarter Than A Slime Mold?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K8HEDqoTPgk

Gross Science: Hookworms and the Myth of the "Lazy Southerner"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7BwgpYexMjk

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

With rows of Dr. Seuss-like flowers hidden deep inside, the corpse flower plays dead to lure some unusual pollinators.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

For a plant that emits an overpowering stench of rotting carcass, you’d think the corpse flower would have a PR problem.

But it’s quite the opposite: Anytime a corpse flower opens up at a botanical garden somewhere in the world visitors flock to catch a whiff and get a glimpse of the giant plant, which can grow up to 10 feet tall when it blooms and generally only does so every two to 10 years.

A corpse flower’s whole survival strategy is based on deception. It’s not a flower and it’s not a rotting dead animal, but it mimics both. Pollination remains out of sight, deep within the plant. KQED’s Deep Look staff was able to film inside a corpse flower, revealing the rarely-seen moment when the plant’s male flowers release glistening strings of pollen.

It’s not that the corpse flower is the only plant to attract pollinators like flies and beetles by putting out bad smells. Nor is it the only one that produces male and female flowers at the same time.

“The fact that it does all of this at this outsized scale – all of this together – is what’s so unique about it, biologically,” said Pati Vitt, senior scientist at the Chicago Botanic Garden.

When a titan arum is ready to flower, a stalk starts to grow out of the soil. Once it has reached four to 10 feet, a red “skirt” unfurls. Though it has the appearance of a petal, it’s really a modified leaf called a spathe that looks like a raw steak.

The yellow stalk underneath is called the spadix and it gives the plant its scientific name, Amorphophallus titanum, or roughly “giant deformed phallus.”

In its native Sumatra, the corpse flower opens for only 24 hours. In captivity, it often lasts longer. With just a day to reproduce, the stakes are high.

--- How many chemicals make up the smell of the corpse flower?

More than 30 chemicals make up the scent of the corpse flower, according to the 2017 paper “Studies on the floral anatomy and scent chemistry of titan arum” by researchers at the University of Mississippi, University of Florida, Gainsville, and Anadolu University in Turkey:

http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr..../botany/issues/bot-1

Some of the chemicals have a pleasant scent. But mostly, the corpse flower at first smells like funky cheese and rotting garlic, as a result of sulphur-smelling compounds. Hours later, the stink changes to what Vanessa Handley, at the University of California Botanical Garden at Berkeley describes as “dead rat in the walls of your house.”

---+ Read the entire article:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....018/01/23/this-giant

---+ For more information:

Great illustration on the lifecycle of the corpse flower by the Chicago Botanic Garden:

https://www.chicagobotanic.org/titan/faq

University of California Davis Botanical Conservatory:

http://greenhouse.ucdavis.edu/conservatory/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

This Mushroom Starts Killing You Before You Even Realize It

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bl9aCH2QaQY

A Real Alien Invasion Is Coming to a Palm Tree Near You

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S6a3Q5DzeBM

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

It’s Okay To Be Smart: How to Figure Out the Day of the Week For Any Date Ever

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=714LTMNJy5M

Above The Noise: Can Genetically Engineered Mosquitoes Help Fight Disease?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CB_h7aheAEM

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Support Deep Look on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Dogs have a famously great sense of smell, but what makes their noses so much more powerful than ours? They're packing some sophisticated equipment inside that squishy schnozz.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

--- How much more powerful is a dog’s sense of smell compared to a human?

According to one estimate, dogs are 10,000-100,000 times more sensitive to smell than humans. They have about 15 times more olfactory neurons that send signals about odors to the brain. The neurons in a dog’s nose are spread out over a much larger and more convoluted area allowing them more easily decipher specific chemicals in the air.

--- Why are dog noses wet?

Dog noses secrete mucus which traps odors in the air and on the ground. When a dog licks its nose, the tongue brings those odors into the mouth allowing it to sample those smells. Dogs mostly cool themselves by panting but the mucus on their noses and sweat from their paws cool through evaporation.

--- Why do dog nostrils have slits on the side?

Dogs sniff about five times per second. The slits on the sides allows exhaled air to vent towards the sides and back. That air moving towards the back of the dog creates a low air pressure region in front of it. Air from in front of the dog rushes in to fill that low pressure region. That allows the nose to actively bring odors in from in front and keeps the exhaled air from contaminating new samples.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....019/02/26/how-your-d

---+ For more information:

The Odor Navigation Project funded NSF Brain Initiative

https://odornavigation.org/

Jacobs Lab of Cognitive Biology at UC Berkeley

http://jacobs.berkeley.edu/

Ecological Fluid Dynamics Lab at University of Colorado Boulder

https://www.colorado.edu/lab/ecological-fluids/

The fluid dynamics of canine olfaction: unique nasal airflow patterns as an explanation of macrosmia (Brent A. Craven, Eric G. Paterson, and Gary S. Settles)

https://royalsocietypublishing.....org/doi/full/10.109

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

The Fantastic Fur of Sea Otters | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zxqg_um1TXI

You've Heard of a Murder of Crows. How About a Crow Funeral? | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ixYVFZnNl6s&t=85s

Newt Sex: Buff Males! Writhing Females! Cannibalism! | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5m37QR_4XNY

What Makes Owls So Quiet and So Deadly? | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a68fIQzaDBY

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

How James Brown Invented Funk | Sound Field

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AihgZv1D5-4

How To Suck Carbon Dioxide Out of the Sky | Hot Mess

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tKtXojkwlK8

What’s the Real Cost of Owning A Pet? | Two Cents

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ma3Mt5BPlTE

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ? to Branden W., Edison Lewis, Vampire Wolf, Haithem Ghanem and Droidtigger who won our GIF CHALLENGE over at the Deep Look Community Tab, by identifying the special region in the canine skull which houses much of the smell ability: https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UC-3SbfTPJsL8fJAPK

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)

Bill Cass

Justin Bull

Daniel Weinstein

David Deshpande

Daisuke Goto

Karen Reynolds

Yidan Sun

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

KW

Shirley Washburn

Tanya Finch

johanna reis

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

Johnnyonnyful

Levi Cai

Jeanine Womble

Michael Mieczkowski

SueEllen McCann

TierZoo

James Tarraga

Willy Nursalim

Aurora Mitchell

Marjorie D Miller

Joao Ascensao

PM Daeley

Two Box Fish

Tatianna Bartlett

Monica Albe

Jason Buberel

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the Templeton Religion Trust, the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

Giant Malaysian leaf insects stay still – very still – on their host plants to avoid hungry predators. But as they grow up, they can't get lazy with their camouflage. They change – and even dance – to blend in with the ever-shifting foliage.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Please support us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

---

You’ll have to look closely to spot a giant Malaysian leaf insect when it’s nibbling on the leaves of a guava or mango tree. These herbivores blend in seamlessly with their surroundings because they look exactly like their favorite food: fruit leaves.

But you can definitely see these fascinating creatures at the California Academy of Sciences, located in the heart of San Francisco's Golden Gate Park, through the spring of 2022.

An ongoing interactive exhibit, ‘Color of Life,’ explores the role of color in the natural world. It's filled with a variety of critters, including Gouldian finches, green tree pythons, Riggenbach's reed frogs, and of course, giant leaf insects.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....947830/these-giant-l

--- What do giant leaf insects eat?

They’re herbivores, so they stick to eating leaves from their habitats, like guava and mango.

--- What’s one main difference between male and female giant leaf insects?

Males can actually fly as they have wings, which they use for mating.

--- But did you know that females don’t need males for mating?

They are facultatively parthenogenetic, which means they sometimes mate or sometimes reproduce asexually. If they mate with a male, they produce both males and females, but if the eggs remain unfertilized – only females are produced.

---+ For more information:

Visit California Academy of Sciences

https://calacademy.org/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

It’s a Bug’s Life: https://www.youtube.com/playli....st?list=PLdKlciEDdCQ

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to the following fans on our YouTube community tab for correctly identifying the type of reproduction female leaf insects can use in the absence of a suitable male - parthenogenesis.

Sylly

Jim Spencer

Rikki Anne

Cara Rose

GOT7 HOT7 THOT7 VISUAL7

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Trae Wright

Justin Bull

Bill Cass

Alice Kwok

Sarah Khalida Mohamad

Stefficael Uebelhart

Daniel Weinstein

Chris B Emrick

Seghan Seer

Karen Reynolds

Tea Torvinen

David Deshpande

Daisuke Goto

Amber Miller

Companion Cube

WhatzGames

Richard Shalumov

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

Robert Amling

Gerardo Alfaro

Mary Truland

Shirley Washburn

Robert Warner

johanna reis

Supernovabetty

Kendall Rasmussen

Sayantan Dasgupta

Cindy McGill

Leonhardt Wille

Joshua Murallon Robertson

Pamela Parker

Roberta K Wright

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

KW

Silvan Wendland

Two Box Fish

Johnnyonnyful

Aurora

George Koutros

monoirre

Dean Skoglund

Sonia Tanlimco

Guillaume Morin

Ivan Alexander

Laurel Przybylski

Allen

Jane Orbuch

Rick Wong

Levi Cai

Titania Juang

Nathan Wright

Syniurge

Carl

Kallie Moore

Michael Mieczkowski

Kyle Fisher

Geidi Rodriguez

JanetFromAnotherPlanet

SueEllen McCann

Daisy Trevino

Jeanne Sommer

Louis O'Neill

riceeater

Katherine Schick

Aurora Mitchell

Cory

Nousernamepls

Chris Murphy

PM Daeley

Joao Ascensao

Nicolette Ray

TierZoo

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

#leafinsects #insect #deeplook

The silent star of classic Westerns is a plant on a mission. It starts out green and full of life. It even grows flowers. But to reproduce effectively it needs to turn into a rolling brown skeleton.

You can learn more about CuriosityStream at https://curiositystream.com/deeplook.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Tumbleweeds might be the iconic props of classic Westerns. But in real life, they’re not only a noxious weed, but one that moves around. Pushed by gusts of wind, they can overwhelm entire neighborhoods, as happened recently in Victorville, California, or become a threat for drivers and an expensive nuisance for farmers.

“They tumble across highways and can cause accidents,” said Mike Pitcairn, who tracks tumbleweeds at the California Department of Food and Agriculture in Sacramento. “They pile up against fences and homes.”

And tumbleweeds aren’t even originally from the West.

Genetic tests have shown that California’s most common tumbleweed, known as Russian thistle, likely came from Ukraine, said retired plant population biologist Debra Ayres, who studied tumbleweeds at the University of California, Davis.

A U.S. Department of Agriculture employee, L. H. Dewey, wrote in 1893 that Russian thistle had arrived in the U.S. through South Dakota in flaxseed imported from Europe in the 1870s.

“It has been known in Russia many years,” Dewey wrote, “and has quite as bad a reputation in the wheat regions there as it has in the Dakotas.” This is where the name Russian thistle originates, said Ayres, although tumbleweeds aren’t thistles.

The weed spread quickly through the United States — on rail cars, through contamination of agricultural seeds and by tumbling.

“They tumble to disperse the seeds,” said Ayres, “and thereby reduce competition.”

A rolling tumbleweed spreads out tens of thousands of seeds so that they all get plenty of sunlight and space.

Tumbleweeds grow well in barren places like vacant lots or the side of the road, where they can tumble unobstructed and there’s no grass, which their seedlings can’t compete with.

--- Where does a tumbleweed come from?

Tumbleweeds start out attached to the soil. Seedlings, which look like blades of grass, sprout at the end of winter. By summer, Russian thistle plants take on their round shape and grow flowers. Inside each flower, a fruit with a seed develops.

Other plants attract animals with tasty fruits, and get them to carry away their seeds and disperse them when they poop.

Tumbleweeds developed a different evolutionary strategy. Starting in late fall, they dry out and die, their seeds nestled between prickly leaves. Gusts of wind easily break dead tumbleweeds from their roots and they roll away, spreading their seeds as they go.

--- How big do tumbleweeds grow?

Mike Pitcairn, of the California Department of Food and Agriculture, said that in the state’s San Joaquin Valley they can grow to be more than 6 feet tall.

--- Are tumbleweeds dangerous?

Yes. They can cause traffic accidents or be a fire hazard if they pile up near buildings.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....922987/why-do-tumble

---+ For more information on the history and biology of Russian thistle, here’s a paper by Debra Ayres and colleagues:

https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/28657/PDF

---+ More great Deep Look episodes:

How Ticks Dig In With a Mouth Full of Hooks

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_IoOJu2_FKE

This Giant Plant Looks Like Raw Meat and Smells Like Dead Rat

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ycUNj_Hv4_Y

Upside-Down Catfish Doesn't Care What You Think

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eurCBOJMrsE

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Above the Noise: Why Is Vaping So Popular?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P9zps5LsVXs

Hot Mess: What Happened to Nuclear Power?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_jEXZZDU6Gk

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the Templeton Religion Trust and the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Join Deep Look on Patreon NOW!

https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

They may be dressed in black, but crow funerals aren't the solemn events that we hold for our dead. These birds cause a ruckus around their fallen friend. Are they just scared, or is there something deeper going on?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

It’s a common site in many parks and backyards: Crows squawking. But groups of the noisy black birds may not just be raising a fuss, scientists say. They may be holding a funeral.

Kaeli Swift, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Washington’s Avian Conservation Lab in Seattle, is studying how crows learn about danger from each other and how they respond to seeing one of their own who has died.

Unlike the majority of animals, crows react strongly to seeing a fellow member of their species has died, mobbing together and raising a ruckus.

Only a few animals like whales, elephants and some primates, have such strong reactions.

To study exactly what may be going on on, Swift developed an experiment that involved exposing local crows in Seattle neighborhoods to a dead taxidermied crow in order to study their reaction.

“It’s really incredible,” she said. “They’re all around in the trees just staring at you and screaming at you.”

Swift calls these events ‘crow funerals’ and they are the focus of her research.

--- What do crows eat?

Crows are omnivores so they’ll eat just about anything. In the wild they eat insects, carrion, eggs seeds and fruit. Crows that live around humans eat garbage.

--- What’s the difference between crows and ravens?

American crows and common ravens may look similar but ravens are larger with a more robust beak. When in flight, crow tail feathers are approximately the same length. Raven tail feathers spread out and look like a fan.

Ravens also tend to emit a croaking sound compared to the caw of a crow. Ravens also tend to travel in pairs while crows tend to flock together in larger groups. Raven will sometimes prey on crows.

--- Why do crows chase hawks?

Crows, like animals whose young are preyed upon, mob together and harass dangerous predators like hawks in order to exclude them from an area and protect their offspring. Mobbing also teaches new generations of crows to identify predators.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....923458/youve-heard-o

---+ For more information:

Kaeli Swift’s Corvid Research website

https://corvidresearch.blog/

University of Washington Avian Conservation Laboratory

http://sefs.washington.edu/research.acl/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Why Do Tumbleweeds Tumble? | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dATZsuPdOnM

Upside-Down Catfish Doesn't Care What You Think | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eurCBOJMrsE

Take Two Leeches and Call Me in the Morning | Deep Look

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O-0SFWPLaII

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from PBS Digital Studios!

Why Climate Change is Unjust | Hot Mess

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q5KjpYK12_c

Is Breakfast the Most Important Meal? | Origin Of Everything

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AxIOGqHQqZM

How the Squid Lost Its Shell | PBS Eons

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S4vxoP-IF2M

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the Templeton Religion Trust and the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Alfalfa leafcutting bees are way better at pollinating alfalfa flowers than honeybees. They don’t mind getting thwacked in the face by the spring-loaded blooms. And that's good, because hungry cows depend on their hard work to make milk.

Join our community on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Please take our annual PBSDS Survey, for a chance to win a T-shirt! https://www.pbsresearch.org/c/r/DL_YTvideo

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

---

Sure, cows are important. But next time you eat ice cream, thank a bee.

Every summer, alfalfa leafcutting bees pollinate alfalfa in an intricate process that gets them thwacked by the flowers when they release the pollen that allows the plants to make seeds. The bees’ hard work came to fruition last week when growers in California finished harvesting the alfalfa seeds that will be grown to make nutritious hay for dairy cows.

This is how it works.

To produce alfalfa seeds, farmers let their plants grow until they bloom. They need help pollinating the tiny purple flowers, so that the female and male parts of the flower can come together and produce fertile seeds. That’s where the grayish, easygoing alfalfa leafcutting bees come in. Seed growers in California release the bees – known simply as cutters – in June and they work hard for a month.

Alfalfa’s flowers keep their reproductive organs hidden away inside a boat-shaped bottom petal called the keel petal, which is held closed by a thin membrane that creates a spring mechanism.

Cutter bees come up to the flower looking for nectar and pollen to feed on. When they land on the flower, the membrane holding the keel petal breaks and the long reproductive structure pops right up and smacks the upper petal or the bee, releasing its yellow pollen. This process is called “tripping the flower.”

When the flower is tripped, pollen falls on its female reproductive organ and fertilizes it; bees also carry pollen away on their hairy bodies and help fertilize other flowers. In a few weeks, each flower turns into a curly pod with seven to 10 seeds growing inside.

Cutters trip 80 percent of flowers they visit, compared to honeybees, which only trip about 10 percent.

---

--- What kind of a plant is alfalfa?

Alfalfa is a legume, like beans and chickpeas. Other legumes also hold their reproductive organs within a keel petal.

--- What do bees use leaves for?

Alfalfa leafcutting bees and other leafcutter bees cut leaf and petal pieces to build their nest inside a hole, such as a nook and cranny in a log. Alfalfa farmers provide bees with holes in styrofoam boards.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....946996/this-bee-gets

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to the following fans for correctly identifying the bee body part coated in pollen, on our Leafcutting Bee - the scopa or scopae!

Punkonthego

GamingCuzWhyNot

Galatians 4:16

Gil AGA

Edison Lewis

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Leonhardt Wille

Justin Bull

Bill Cass

Sarah Khalida Mohamad

Daniel Weinstein

Chris B Emrick

Karen Reynolds

Tea Torvinen

David Deshpande

Daisuke Goto

Companion Cube

WhatzGames

Richard Shalumov

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

Gerardo Alfaro

Robert Amling

Shirley Washburn

Robert Warner

Supernovabetty

johanna reis

Kendall Rasmussen

Pamela Parker

Sayantan Dasgupta

Joshua Murallon Robertson

Cindy McGill

Kenia Villegas

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

Aurora

Dean Skoglund

Silvan Wendland

Ivan Alexander

monoirre

Sonia Tanlimco

Two Box Fish

Jane Orbuch

Allen

Laurel Przybylski

Johnnyonnyful

Rick Wong

Levi Cai

Titania Juang

Nathan Wright

Carl

Michael Mieczkowski

Kyle Fisher

JanetFromAnotherPlanet

Kallie Moore

SueEllen McCann

Geidi Rodriguez

Louis O'Neill

Edwin Rivas

Jeanne Sommer

Katherine Schick

Aurora Mitchell

Cory

Ricardo Martinez

riceeater

Daisy Trevino

KW

PM Daeley

Joao Ascensao

Chris Murphy

Nicolette Ray

TierZoo

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

KQED Science on kqed.org: http://www.kqed.org/science

Facebook Watch: https://www.facebook.com/DeepLookPBS/

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

#leafcutter #bees #deeplook

You might suppose this catfish is sick, or just confused. But swimming belly-up actually helps it camouflage and breathe better than its right-side-up cousins.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Normally, an upside-down fish in your tank is bad news. As in, it’s time for a new goldfish.

That’s because most fish have an internal air sac called a “swim bladder” that allows them to control their buoyancy and orientation. They fill the bladder with air when they want to rise, and deflate it when they want to sink. Fish without swim bladders, like sharks, have to swim constantly to keep from dropping to the bottom.

If an aquarium fish is listing to one side or flops over on its back, it often means it has swim bladder disease, a potentially life-threatening condition usually brought on parasites, overfeeding, or high nitrate levels in the water.

But for a few remarkable fish, being upside-down means everything is great.

In fact, seven species of catfish native to Central Africa live most of their lives upended. These topsy-turvy swimmers are anatomically identical to their right-side up cousins, despite having such an unusual orientation.

People’s fascination with the odd alignment of these fish goes back centuries. Studies of these quizzical fish have found a number of reasons why swimming upside down makes a lot of sense.

In an upside-down position, fish produce a lot less wave drag. That means upside-down catfish do a better job feeding on insect larvae at the waterline than their right-side up counterparts, who have to return to deeper water to rest.

There’s something else at the surface that’s even more important to a fish’s survival than food: oxygen. The gas essential to life readily dissolves from the air into the water, where it becomes concentrated in a thin layer at the waterline — right where the upside-down catfish’s mouth and gills are perfectly positioned to get it.

Scientists estimate that upside-down catfishes have been working out their survival strategy for as long at 35 million years. Besides their breathing and feeding behavior, the blotched upside-down catfish from the Congo Basin has also evolved a dark patch on its underside to make it harder to see against dark water.

That coloration is remarkable because it’s the opposite of most sea creatures, which tend to be darker on top and lighter on the bottom, a common adaptation called “countershading” that offsets the effects of sunlight.

The blotched upside-down catfish’s “reverse” countershading has earned it the scientific name negriventris, which means black-bellied.

--- How many kinds of fish swim upside down?

A total of seven species in Africa swim that way. Upside-down swimming may have evolved independent in a few of the species – and at least one more time in a catfish from Asia.

--- How do fish stay upright?

They have an air-filled swim bladder on the inside that that they can fill or deflate to maintain balance or to move up or down in the water column.

--- What are the benefits of swimming upside down?

Upside down, a fish swims more efficiently at the waterline, where there’s more oxygen and better access to some prey.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....922038/the-mystery-o

---+ For more information:

The California Academy of Sciences has upside-down catfish in its aquarium collection: https://www.calacademy.org/exh....ibits/steinhart-aqua

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Take Two Leeches and Call Me in the Morning

https://youtu.be/O-0SFWPLaII

This Is Why Water Striders Make Terrible Lifeguards

https://youtu.be/E2unnSK7WTE

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

PBS Eons: What a Dinosaur Looks Like Under a Microscope

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4rvgiDXc12k

Origin of Everything: The Origin of Race in the USA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CVxAlmAPHec

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation Fund and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

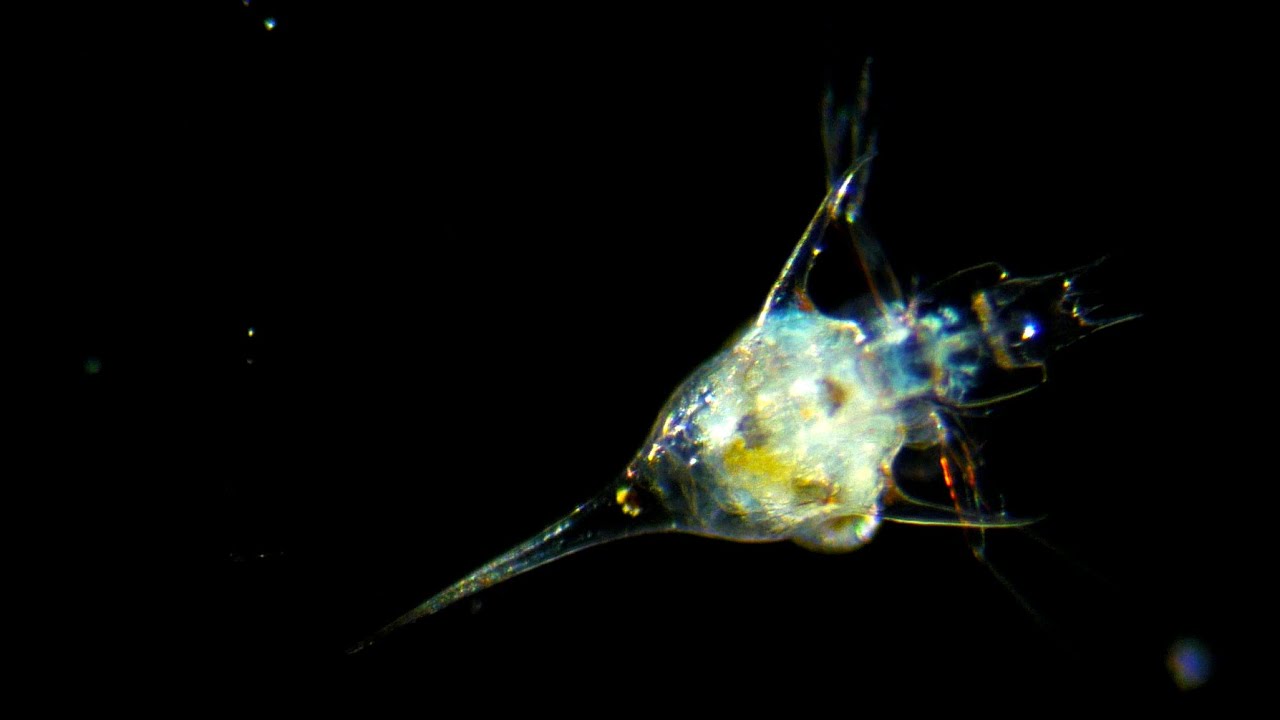

Most plankton are tiny drifters, wandering in a vast ocean. But where wind and currents converge they become part of a grander story … an explosion of vitality that affects all life on Earth, including our own.

SUBSCRIBE: http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is supported by HopeLab, The David B. Gold Foundation; S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Vadasz Family Foundation; Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

Mammalian moms, you're not alone! A female tsetse fly pushes out a single squiggly larva almost as big as herself, which she nourished with her own milk.

Please join our community on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

---

Mammalian moms aren’t the only ones to deliver babies and feed them milk. Tsetse flies, the insects best known for transmitting sleeping sickness, do it too.

A researcher at the University of California, Davis is trying to understand in detail the unusual way in which these flies reproduce in order to find new ways to combat the disease, which has a crippling effect on a huge swath of Africa.

When it’s time to give birth, a female tsetse fly takes less than a minute to push out a squiggly yellowish larva almost as big as itself. The first time he watched a larva emerge from its mother, UC Davis medical entomologist Geoff Attardo was reminded of a clown car.

“There’s too much coming out of it to be able to fit inside,” he recalled thinking. “The fact that they can do it eight times in their lifetime is kind of amazing to me.”

Tsetse flies live four to five months and deliver those eight offspring one at a time. While the larva is growing inside them, they feed it milk. This reproductive strategy is extremely rare in the insect world, where survival usually depends on laying hundreds or thousands of eggs.

--- What is sleeping sickness?

Tsetse flies, which are only found in Africa, feed exclusively on the blood of humans and other domestic and wild animals. As they feed, they can transmit microscopic parasites called trypanosomes, which cause sleeping sickness in humans and a version of the disease known as nagana in cattle and other livestock. Sleeping sickness is also known as human African trypanosomiasis.

--- What are the symptoms of sleeping sickness?

The disease starts with fatigue, anemia and headaches. It is treatable with medication, but if trypanosomes invade the central nervous system they can cause sleep disruptions and hallucinations and eventually make patients fall into a coma and die.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....956004/a-tsetse-fly-

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

“Parasites Are Dynamite” Deep Look playlist:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C2Jw5ib-s_I&list=PLdKlciEDdCQACmrtvWX7hr7X7Zv8F4nEi

---+ Shoutout!

?Congratulations ?to these fans on our YouTube community tab who correctly identified the function of the black protuberances on a tsetse fly larva - polypneustic lobes:

Jeffrey Kuo

Lizzie Zelaya

Art3mis YT

Garen Reynolds

Torterra Grey8

Despite looking like a head, they’re actually located at the back of the larva, which used them to breathe while growing inside its mother. The larva continues to breathe through the lobes as it develops underground.

---+ Thank you to our Top Patreon Supporters ($10+ per month)!

Alice Kwok

Allen

Amber Miller

Aurora

Aurora Mitchell

Bethany

Bill Cass

Blanca Vides

Burt Humburg

Caitlin McDonough

Cameron

Carlos Carrasco

Chris B Emrick

Chris Murphy

Cindy McGill

Companion Cube

Daisuke Goto

Daniel Weinstein

David Deshpande

Dean Skoglund

Edwin Rivas

Egg-Roll

Elizabeth Ann Ditz

Geidi Rodriguez

Gerardo Alfaro

Guillaume Morin

Jane Orbuch

Joao Ascensao

johanna reis

Johnnyonnyful

Josh Kuroda

Joshua Murallon Robertson

Justin Bull

Kallie Moore

Karen Reynolds

Katherine Schick

Kathleen R Jaroma

Kendall Rasmussen

Kristy Freeman

KW

Kyle Fisher

Laura Sanborn

Laurel Przybylski

Leonhardt Wille

Levi Cai

Louis O'Neill

luna

Mary Truland

monoirre

Natalie Banach

Nathan Wright

Nicolette Ray

Noreen Herrington

Osbaldo Olvera

Pamela Parker

Richard Shalumov

Rick Wong

Robert Amling

Robert Warner

Roberta K Wright

Sarah Khalida Mohamad

Sayantan Dasgupta

Shelley Pearson Cranshaw

Silvan Wendland

Sonia Tanlimco

SueEllen McCann

Supernovabetty

Syniurge

Tea Torvinen

TierZoo

Titania Juang

Trae Wright

Two Box Fish

WhatzGames

---+ Follow KQED Science and Deep Look:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kqedscience/

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation, Campaign 21 and the members of KQED.

#tsetsefly #sleepingsickness #deeplook

Support Deep Look on Patreon!! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

The notorious death cap mushroom causes poisonings and deaths around the world. If you were to eat these unassuming greenish mushrooms by mistake, you wouldn’t know your liver is in trouble until several hours later. The death cap has been spreading across California. Can scientists find a way to stop it?

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK: a new ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

Find out more on KQED Science:

http://ww2.kqed.org/science/20....16/02/23/this-mushro

Where do death cap mushrooms grow?

In California, they grow mainly under coast live oaks. They have also been found under pines, and in Yosemite Valley under black oaks.

Why do death caps grow under trees?

As many fungi do, death cap mushrooms live off of trees, in what’s called a mycorrhizal relationship. They send filaments deep down to the trees’ roots, where they attach to the very thin root tips. The fungi absorb sugars from the trees and give them nutrients in exchange.

Where do California’s death cap mushrooms come from?

Biologist Anne Pringle, at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, has done research that shows that death caps likely snuck into California from Europe attached to the roots of imported plants, as early as 1938.

How deadly are death cap mushrooms?

Between 2010 and 2015, five people died in California and 57 became sick after eating the unassuming greenish mushrooms, according to the California Poison Control System. One mushroom cap is enough to kill a human being, and they’re also poisonous to dogs. Death caps are believed to be the number one cause of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide.

What happens if you eat a death cap mushroom?

A toxin in the mushroom destroys your liver cells. Dr. Kent Olson, co-medical director of the San Francisco Division of the California Poison Control System, said that for the first six to 12 hours after they eat the mushroom, victims of the death cap feel fine. During that time, a toxin in the mushroom is quietly injuring their liver cells. Patients then develop severe abdominal pain, diarrhea and vomiting. “They can become very rapidly dehydrated from the fluid losses,” said Olson. Dehydration can cause kidney failure, which compounds the damage to the liver. For the most severe cases, the only way to save the patient is a liver transplant.

For more information on the death cap:

Bay Area Mycological Society’s page with photos: http://bayareamushrooms.org/mu....shroommonth/amanita_

Rod Tulloss’ detailed description: http://www.amanitaceae.org/?Amanita%20phalloides

More great Deep Look episodes:

What Happens When You Zap Coral With The World's Most Powerful X-ray Laser?

https://youtu.be/aXmCU6IYnsA

These 'Resurrection Plants' Spring Back to Life in Seconds

https://youtu.be/eoFGKlZMo2g

See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It's Okay to Be Smart: Your Salad Is Trying To Kill You

https://youtu.be/8Ofgj2KDbfk

It's Okay to Be Smart: The Oldest Living Things In The World

https://youtu.be/jgspUYDwnzQ

For more content from your local PBS and NPR affiliate:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the David B. Gold Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook #mushroom #deathcap

Those hundreds of powerful suckers on octopus arms do more than just stick. They actually smell and taste. This contributes to a massive amount of information for the octopus’s brain to process, so octopuses depend on their eight arms for help. (And no, it's not 'octopi.')

To keep up with Amy Standen, subscribe to her podcast The Leap - a podcast about people making dramatic, risky changes:

https://ww2.kqed.org/news/programs/the-leap/

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Everyone knows that an octopus has eight arms. And similar to our arms it uses them to grab things and move around. But that’s where the similarities end. Hundreds of suckers on each octopus arm give them abilities people can only dream about.

“The suckers are hands that also smell and taste,” said Rich Ross, senior biologist and octopus aquarist at the California Academy of Sciences.

Suckers are “very similar to our taste buds, from what little we know about them,” said University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, cephalopod biologist William Kier.

If these tasting, smelling suckers make you think of a human hand with a tongue and a nose stuck to it, that’s a good start. It all stems from the unique challenges an octopus faces as a result of having a flexible, soft body.

“This animal has no protection and is a wonderful meal because it’s all muscle,” said Kier.

So the octopus has adapted over time. It has about 500 million neurons (dogs have around 600 million), the cells that allow it to process and communicate information. And these neurons are distributed to make the most of its eight arms. An octopus’ central brain – located between its eyes – doesn’t control its every move. Instead, two thirds of the animal’s neurons are in its arms.

“It’s more efficient to put the nervous cells in the arm,” said neurobiologist Binyamin Hochner, of Hebrew University, in Jerusalem. “The arm is a brain of its own.”

This enables octopus arms to operate somewhat independently from the animal’s central brain. The central brain tells the arms in what direction and how fast to move, but the instructions on how to reach are embedded in each arm.

Octopuses have also evolved mechanisms that allow their muscles to move without the use of a skeleton. This same muscle arrangement enables elephant trunks and mammals’ tongues to unfurl.

“The arrangement of the muscle in your tongue is similar to the arrangement in the octopus arm,” said Kier.

In an octopus arm, muscles are arranged in different directions. When one octopus muscle contracts, it’s able to stretch out again because other muscles oriented in a different direction offer resistance – just as the bones in vertebrate bodies do. This skeleton of muscle, called a muscular hydrostat, is how an octopus gets its suckers to attach to different surfaces.

--- How many suction cups does an octopus have on each arm?

It depends on the species. Giant Pacific octopuses have up to 240 suckers on each arm.

--- Do octopuses have arms or tentacles?

Octopuses have arms, not tentacles. “The term ‘tentacle’ is used for lots of fleshy protuberances in invertebrates,” said Kier. “It just happens that the eight in octopuses are called arms.”

--- Can octopuses regrow a severed arm?

Yes!

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2....017/02/14/if-your-ha

---+ For more information:

The octopus research group at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gN81dtxilhE

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

You're Not Hallucinating. That's Just Squid Skin.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0wtLrlIKvJE

Watch These Frustrated Squirrels Go Nuts!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZUjQtJGaSpk

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

It’s Okay To Be Smart: Is This A NEW SPECIES?!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=asZ8MYdDXNc

BrainCraft: Your Brain in Numbers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FFcbnf07QZ4

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by HopeLab, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

#deeplook

It's an all-out brawl for prime beach real estate! These Caribbean crabs will tear each other limb from limb to get the best burrow. Luckily, they molt and regrow lost legs in a matter of weeks, and live to fight another day.

You can learn more about CuriosityStream at https://curiositystream.com/deeplook

Help Deep Look grow by supporting us on Patreon!!

https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

PBS Digital Studios Mega-playlist:

https://www.youtube.com/playli....st?list=PL1mtdjDVOoO

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

On the sand-dune beaches where they live, male blackback land crabs do constant battle over territory. The stakes are high: If one of these baby-faced crabs secures a winning spot, he can invite a mate into his den, six or seven feet beneath the surface.

With all this roughhousing, more than feelings get hurt. The male crabs inevitably lose limbs and damage their shells in constant dust-ups. Luckily, like many other arthropods, a group that includes insects and spiders, these crabs can release a leg or claw voluntarily if threatened. It’s not unusual to see animals in the field missing two or three walking legs.

The limbs regrow at the next molt, which is typically once a year for an adult. When a molt cycle begins, tiny limb buds form where a leg or a claw has been lost. Over the next six to eight weeks, the buds enlarge while the crab reabsorbs calcium from its old shell and secretes a new, paper-thin one underneath.

In the last hour of the cycle, the crab gulps air to create enough internal pressure to pop open the top of its shell, called the carapace. As the crab pushes it way out, the same internal pressure helps uncoil the new legs. The replacement shell thickens and hardens, and the crab eats the old shell.

--- Are blackback land crabs edible?

Yes, but they’re not as popular as the major food species like Dungeness and King crab.

--- Where do blackback land crabs live?

They live throughout the Caribbean islands.

--- Does it hurt when they lose legs?

Hard to say, but they do have an internal mechanism for releasing limbs cleanly that prevents loss of blood.

---+ Read the entire article on KQED Science:

https://www.kqed.org/science/1....933532/whack-jab-cra

---+ For more information:

The Crab Lab at Colorado State University:

https://rydberg.biology.colostate.edu/mykleslab/

---+ More Great Deep Look episodes:

Want a Whole New Body? Ask This Flatworm How

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m12xsf5g3Bo

Daddy Longlegs Risk Life ... and Especially Limb ... to Survive

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tjDmH8zhp6o

---+ See some great videos and documentaries from the PBS Digital Studios!

Origin of Everything: The Origin of Gender

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5e12ZojkYrU

Hot Mess: Coral Reefs Are Dying. But They Don’t Have To.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MUAsFZuFQvQ

---+ Follow KQED Science:

KQED Science: http://www.kqed.org/science

Tumblr: http://kqedscience.tumblr.com

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/kqedscience

---+ About KQED

KQED, an NPR and PBS affiliate in San Francisco, CA, serves Northern California and beyond with a public-supported alternative to commercial TV, Radio and web media.

Funding for Deep Look is provided in part by PBS Digital Studios. Deep Look is a project of KQED Science, which is also supported by the National Science Foundation, the Templeton Religion Trust, the Templeton World Charity Foundation, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation, the Vadasz Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Fuhs Family Foundation and the members of KQED.

---+ Shoutout!

Congratulations to ?Jen Wiley?, who was the first to correctly ID the species of crab in our episode over at the Deep Look Community Tab:

https://www.youtube.com/channe....l/UC-3SbfTPJsL8fJAPK

#deeplook #pbsds #crab

OK. Maybe you would. But the lengths they have to go to to stock up for the winter *will* surprise you. When you see how carefully they arrange each acorn, you might just need to reorganize your pantry.

You can learn more about CuriosityStream at https://curiositystream.com/deeplook.

Join Deep Look on Patreon NOW! https://www.patreon.com/deeplook

You can learn more about CuriosityStream at https://curiositystream.com/deeplook .

SUBSCRIBE to Deep Look! http://goo.gl/8NwXqt

DEEP LOOK is a ultra-HD (4K) short video series created by KQED San Francisco and presented by PBS Digital Studios. See the unseen at the very edge of our visible world. Get a new perspective on our place in the universe and meet extraordinary new friends. Explore big scientific mysteries by going incredibly small.

* NEW VIDEOS EVERY OTHER TUESDAY! *

Have you ever wondered why woodpeckers pound so incessantly?

In the case of acorn woodpeckers – gregarious black and red birds in California’s oak forests – they’re building an intricate pantry, a massive, well-organized stockpile of thousands of acorns to carry them through the winter.

“They’re the only animals that I know of that store their acorns individually in holes in trees,” said biologist Walter Koenig, of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, who has studied acorn woodpeckers for decades at the University of California’s Hastings Natural History Reservation in Carmel Valley.

Over generations, acorn woodpeckers can drill thousands of small holes into one or several trees close to each other, giving these so-called granaries the appearance of Swiss cheese.

This sets them apart from other birds that drop acorns into already-existing cavities in trees, and animals like squirrels and jays that bury acorns in the ground.

In spring and summer, hikers in California commonly see acorn woodpeckers while the birds feed their chicks and care for their granaries. They don’t mind people staring at them and they’re easy to find. They greet each other with loud cries that sound like “waka-waka-waka.”

They’re also found in Oregon, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas, and all the way south to Colombia.

These avian performers are constantly tapping, drilling and pounding at their granaries.

“They’ll usually have a central granary, maybe two trees that a group is using,” said Koenig. “Those trees are going to be close together.”

Acorn woodpeckers make their granaries in pines, oaks, sycamores, redwoods and even in the palm trees on the Stanford University campus.

Their holes rarely hurt the trees. The birds only bore into the bark, where there’s no sap, or they make their granaries in snags.